History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls - the Organic Gem Perfected by Nature - Page 3

Open FREE Unlimited Store Join Our Newsletter

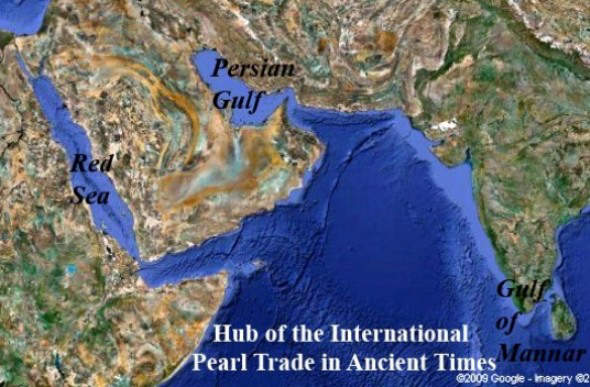

An assessment of the Gulf of Mannar region as another possible region where the discovery and appreciation of pearls first began

The Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka is another very ancient source of pearls, and pre-historic people living in the southern coast of India and the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka might have stumbled upon the first pearls discovered by man in this region, during the harvesting of pearl oysters for food.

The Gulf of Mannar between India and Sri Lanka (Ceylon), is the other most ancient source of pearls in the world. The pearl banks in this region are situated both closer to the Sri Lankan coast as well as the South Indian coast. However, the pearl banks closer to the Sri Lankan coast were more extensive and lucrative than the pearl banks near the South Indian coast. Pre-historic peoples living closer to the coastal areas in the northwestern Sri Lanka and southern India may have stumbled upon the first pearls discovered in this region, during their quest for food, just as much as it happened in the Persian Gulf in pre-historic times. Such discovery of pearls might have occurred independent of the discovery that took place in the Persian Gulf.

Archeological evidence supporting the use of pearls in pre-historic times are almost non-existent both from the Sri Lanka and southern India, though such evidence exists for mother-of-pearl beads and other shell beads from univalve mollusks in the ancient Mohendajaro and Harappa civilizations (2,600-1,900 B.C.) of the Indus Valley, a civilization that built the first planned cities and controlled vast territories through trade and religion rather than warfare. The Harappans established trade contacts with ancient Mesopotamia, and traded in pearls, gems, copper and ivory in exchange for Mesopotamian wool, leather and olive oil. Unlike in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea region where extensive archaeological excavations had taken place of both historic and pre-historic sites, in Sri Lanka and India most of the excavations had been largely limited to historic sites, of which information was already available from ancient written records, but whose existence had been obliterated by the ravages of time, buried by mounds of earth and forest growth. In Sri Lanka, most of the ancient sites mentioned in the two written historical chronicles of the Island nation, the Mahawamsa (Great Chronicle) and the Chulawamsa (Lesser Chronicle) have now been excavated. Archaeologists have now diverted their attention to pre-historic sites that are not mentioned in the two chronicles, extending to pre-Vijayan times, the period before King Vijaya, the north Indian prince who settled in the Island with his followers in the 6th-century B.C., and from whom the Sinhalese claim their descent.

Pearl Banks of the Gulf of Mannar

Examination of the coastal region of Sri Lanka as a possible area where the discovery and appreciation of pearls first began

Evidence for the large scale harvesting of oysters as a source of food have emerged from a pre-historic stone-age site at Pallemalala in southeastern Sri Lanka 6,000 years old (4,000 years B.C.)

The credit for the discovery of the site goes to an alert school boy who reported the digging out of human skeletons in a shell mine by a shell miner, to his teacher

In one of the significant archaeological discoveries made in the southeastern coastal region of Sri Lanka in 1997 by a team of archaeologists of the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology led by archeologist Raj Somadeva, the first evidence was unearthed of extensive use of saltwater oysters as a source of food by a pre-historic stone age community that lived in the coastal village of Pallemalala in the Hambantota district of southeastern Sri Lanka. The site discovered in a shell midden by a shell miner, was reported by an alert schoolboy to his teacher. A large part of the credit for the discovery goes to this school boy, without whose alertness the discovery might have gone unreported. The pre-historic site contained several skeletal remains of stone age men and implements used by them.

The underground shell middens were formed when pre-historic men discarded the shells after eating the roasted contents of the oyster

A shell midden is an underground mound of shells covering a large area, that was formed when pre-historic stone age man, discarded the shells of mollusks, mainly oysters that he had consumed over a long period of time. Over the years such mounds reached enormous proportions, and formed a solid base of calcareous material that encouraged human settlements. It appeared that primitive men collected the mollusks from the nearby lagoon or bay that had presently dried up. Most of the shells in the midden had been broken up by opening the bivalve shells with some crude stone implement.

Archaeologists also unearthed evidence that the primitive settlers on the shell midden, were stone-age men from the mesolithic period, who were hunter gatherers

Archaeologists discovered the living floor of the primitive settlers when excavating the site to a depth of about three feet into the shell mound. Bones of animal skeletons recovered from the living floor appeared to belong to around 50 different animal species, that included deer, wild boar, wild buffalo, hare, mouse etc. Among other discoveries were a primitive grinding stone, and the remnants of a fire place, used for roasting not only the carcass of hunted animals, but also the fleshy contents of the mollusks harvested from the bay or lagoon.

Archaeologists also unearthed seven well-preserved human skeletons in the flexed position of which at least one belonged to a female

Further excavations carried out by the archaeologists, going down by another three feet below the living floor, led to the discovery of a burial floor, beneath the living floor, where seven well-preserved adult skeletons in flexed positions were unearthed. At least one of the seven skeletons were determined by anthropologists to belong to a female.

Anatomical features of the skeletons showed distinct features related to the aboriginal Veddahs of Sri Lanka, an Austro-Asian indigenous stock related to the aborigines of Australia, Malayan sakais, and the hos and birhos of eastern India

Anthropological and cultural evidence showed that these primitive stone age people were genetically related to Sri Lanka's inland aboriginal inhabitants, the Veddahs, with their thick-set skull, long head, broad nose, pronounced brow-ridges and prognathous or protruding jaw, and were thus allied to the Austro-Asian stock of indigenous peoples, such as the Australian aborigines, the Malayan sakais, and the Mundari-speaking peoples of eastern India, such as the Hos and the Birhos. Pallemalala stone age man appears to belong to the middle stone age or mesolithic period, as they possessed no polished stone implements, or engaged in activities such as agriculture or domestication of animals. Archeologist Raj Somadeva has estimated that there are at least 50 such shell middens in the vicinity of the present excavation site. Similar shell middens had been discovered in the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean before, but this is the first ever shell midden discovered in Sri Lanka. All pre-historic sites discovered before in Sri Lanka were found in sheltered rock caves, but this is the first time an open air pre-historic site had been discovered in Sri Lanka. The oldest pre-historic site discovered in Sri Lanka, containing the skeleton of early cave-dwelling mesolithic "Balangoda man" is around 37,000 years old.

The skeletal remains found in the lower layers of the shell midden have been tentatively estimated to be around 6,000 years old (4,000 years B.C.), but the shell midden itself originates from a much older period

Archaeologists have tentatively dated the Pallemalala pre-historic skeletal remains as belonging to 4,000 years B.C. (6,000 years B.P.), until an accurate determination by carbon-dating is done on the skeletal remains and the shell midden. The shell midden is undoubtedly much older than the skeletal remains, as the pre-historic people that chose to live on the midden, came from a much recent era, whereas the shell midden itself was built up by discarded shells of mollusks eaten by pre-historic men that lived in a much older era. Hence, the oyster eating men who were responsible for creating the large mounds of open shells, lived in a period much older than 6,000 years, perhaps as old as 37,000 BP, the age of the earliest mesolithic "Balangoda man" skeletons discovered in the Fa-Hien caves near Bulathsinhala. .

The significance of the Pallemalala discoveries

The Pallemalala discoveries have a great significance with respect to the ancient history of the usage and appreciation of pearl oysters and pearls. The significance of this discovery are as follows :-

1) The discovery establishes the fact that Sri Lanka was one of the most ancient sources of pearl oysters and pearls in the world. The fact that oyster-eating pre-historic populations lived in the coastal areas of Sri Lanka, 6,000 to 40,000 years BP, that was responsible for the building up of enormous shell middens, estimated to be around 50, consisting mostly of discarded oyster shells, shows that oyster-producing beds were quite common in the past, in the shallow waters surrounding the Island, that was able to sustain such pre-historic people for long periods of time.

2) The discovery also shows that in ancient times pearl banks was not only restricted to the northwestern coastline of Sri Lanka, around the Mannar area, but were also found abundantly in the directly opposite southeastern coastline of the Island, around the ancient port city of Hambantota, that opens the possibility that such pearl oyster beds were also found in the numerous shallow bays and lagoons right round the Island. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before more shell middens are discovered elsewhere in the Island.

3) The fact that oyster-eating pre-historic populations lived in the coastal regions of the Island 6,000 - 40,000 BP, gives rise to the strong possibility that such pre-historic people were among the first to stumble upon the rare pearls that were occasionally found in these oysters, and thus deserve to be given the credit for discovering natural pearls, and appreciating their beauty. Little wonder then Sri Lanka was known in ancient times as an important source of pearls, with sea faring people like the Phoenicians, and later the ancient Greeks and Romans reaching the northwestern coasts of the Island, to purchase pearls.

Evidence from the early historical period of Sri Lanka that shows the antiquity of the natural pearl industry and trade

Sri Lanka has a recorded history of almost 2,500 years beginning from the mid 6th-century B.C. and "The Mahawamsa" (Great Chronicle) that records the history of the Island is considered to be one of the world's longest unbroken historical accounts

The historical period of Sri Lanka begins with the Indo-Aryan migration to the Island in the mid 6th-century B.C. (around 543 B.C.), by a north Indian prince, Vijaya and his 700 followers, who settled in the Island and from whom the majority ethnic group in Srl Lanka, the Sinhalese, claim their descent. The history of the Island nation beginning with the arrival of Prince Vijaya, was recorded in Pali language by Buddhist monks of the Mahavihara (Great Temple), on "Ola" palm leaves (similar to papyrus leaves), beginning with the 3rd-century B.C. and subsequently compiled into a single document known as the "Mahawamsa" (Greater Chronicle) in the 5th-century A.D. by the Buddhist Monk Mahanama, who is usually credited with the authorship of the ancient document. Thus, the "Mahawamsa" consists of almost 1,000 years of recorded history of Sri Lanka, dealing with the life and deeds of all kings who ruled during this period.

The history of the Island nation after the 5th-century A.D. was compiled in a companion volume known as the "Chulawamsa" (Lesser Chronicle), also by Buddhist monks and covered a period of 14 centuries, from the 5th-century A.D. until the total British take-over of the Island in 1815. While the "Mahawamsa" was compiled by a single author in the 5th-century A.D. the "Chulawamsa" was compiled and progressively revised and expanded by several authors over the years until 1815. Some authorities prefer to refer to the combined volumes of "Mahawamsa" and "Chulawamsa" as "The Mahawamsa" instead of differentiating between the two volumes. The combined volumes spanning a period of almost 2,500 years, is considered to be one of the world's longest unbroken historical accounts.

Reference to pearls in the Mahawamsa

The Mahawamsa records stories of battles and invasions, court intrigues, the construction of palace complexes, rock fortresses like Sigiriya, giant Buddhist stupas (like the pyramids of Egypt), and giant irrigation schemes, with large reservoirs and long irrigation channels. that has marveled the modern-day irrigation engineers. It also records various aspects of the lives of ordinary citizens, including the vocations they are engaged in such as farming, blacksmithing, gold-smithing and jewelry designing, stone and rock-carving, brass founding, carpentry, pottery, weaving etc. The Mahawamsa also refers to different kinds of pearls and other gemstones like sapphire, beryls and rubies found in Sri Lanka, and occasions such pearls and gemstones were sent as gifts by the king of Sri Lanka to monarchs in neighboring India. Two such references to pearls are found in Chapter 7 - Consecration of King Vijaya and Chapter 11 -Consecration of King Devanampiyatissa.

The following are relevant extracts (in italics) from chapters 7 and 11 of the English translation of the Mahawamsa translated by Mabel Haynes Bode, from the German version written by Wilhelm Geiger in 1920.

Chapter 7 - Consecration of Vjaya - Reference to pearls around 543 B.C.

When they had founded settlements in the land the ministers all came together and spoke thus to the prince: `Sire, consent to be consecrated as king.’ But, in spite of their demand, the prince refused the consecration, unless a maiden of a noble house were consecrated as queen (at the same time).

But the ministers, whose minds were eagerly bent upon the consecrating of their lord, and who, although the means were difficult, had overcome all anxious fears about the matter, sent people, entrusted with many precious gifts, jewels, pearls, and so forth, to the city of Madhura[16] in southern (India), to woo the daughter of the Pandu king for their lord, devoted (as they were) to their ruler; and they also (sent to woo) the daughters of others for the ministers and retainers.

The first extract from Chapter 7, refers to Prince Vijaya's refusal to be consecrated as king, unless he married a maiden from a noble house, who would be consecrated as queen at the same time. Prince Vijaya's ministers and closest advisers immediately set about the task of finding a princess of a noble family to fulfill his wishes. Realizing that the closest kingdom from where they could find a princess of noble birth, was the Dravidian Pandu kingdom of South India, the ministers sent a delegation to the city of Madurai in southern India, carrying the proposal to the Pandu King, to ask for his daughter's hand for the Prince. As was the tradition at that time, the delegation carried several valuable gifts for the Pandu King, that included among others jewels, precious stones (sapphires, rubies, beryls etc.) and pearls, for which Sri Lanka was renowned at that time. The mission was successful and delegation returned not only with the Pandu King's daughter accompanied by more valuable reciprocal gifts for Prine Vijaya, but also fair maidens for the ministers of the Prince. The story not only signifies an Indo-Aryan-Dravidian alliance, at the beginning of the historical period in Sri Lanka, but also establishes the fact that Sri Lanka was a source of pearls and other precious stones such as rubies, sapphires and beryls since ancient times.

Chapter 11 - The Consecration of Devanampiyatissa - Reference to pearls around 306 B.C.

Pearls of the eight kinds, namely

horse-pearl, elephant -pearl, waggon-pearl, myrobalan -pearl, bracelet-pearl,

ring-pearl, kakudha fruit-pearl, and common (pearls) came forth out of the ocean

and lay upon the shore in heaps.

All this was the effect of Devanampiyatissa’s merit. Sapphire, beryl, ruby,

these gems and many jewels and those pearls and those bamboo-stems they brought,

all in the same week, to the king.

When the king saw them he was glad at heart and thought: ‘My friend Dhammasoka and nobody else is worthy to have these priceless treasures ; I will send them to him as a gift.’ For the two monarchs, Devanampiyatissa and Dhammasoka already had been friends a long time, though they had never seen each other.

The king sent four persons appointed as his envoys : his nephew Maharittha, who was the chief of his ministers, then his chaplain, a minister and his treasurer,[4] attended by a body of retainers, and he bade them take with them those priceless jewels, the three kinds of precious stones, and the three stems (like) waggon-poles, and a spiral shell winding to the right, and the eight kinds of pearls. When they had embarked at Jambukola[5] and in seven days had reached the haven[6] in safety, and from thence in seven days more had come to Pataliputta, they gave those gifts into the hands of king Dhammasoka. When he saw them he rejoiced greatly. Thinking: ‘Here I have no such precious things’ the monarch, in his joy, bestowed on Arittha the rank of a commander in his army, on the brahman the dignity of chaplain, to the minister he gave the rank of staff-bearer, and to the treasurer that of a guild-lord.[7]

Commentary on King Devanampiyatissa (306 B.C.-266 B.C.)

Grand miracles occurred during the consecration of King Devanampiya Tissa. Jewels buried in earth rose to the surface, pearls in deep oceans came to the shore and piled up in the shore and bamboo trees started to look like they were made out of silver. King Devanampiya Tissa thought that these pearls and gems should be sent to his great friend, King Dharmashoka of India. King Dharmashoka and King Devanampiya Tissa were great friends for many years but had never seen each other. King Devanampiya Tissa sent a mission to India with many jewels and pearls and other gifts for his friend, King Dharmashoka.

The fact that king Ashoka was impressed by the gifts sent by king Devanampiyatissa, to the extent that he bestowed special honors and titles on the members of the delegation who carried them to India, speaks of the high-quality of the precious stones and pearls that originated in Sri Lanka at that time

King Devanampiyatissa was no doubt a pious, benevolent and one of the greatest kings that ruled Sri Lanka for 40 years from 306 B.C. to 266 B.C. Buddhism was introduced to Sri Lanka during his period of rule, and the king was the first Buddhist convert. The Buddhist missionary who successfully converted the king to Buddhism was none other than Mahindra (Mahinda), the son of the mighty Mauryan king of India, king Ashoka (Dharmasoka) who himself had converted to Buddhism, after the bloody military campaigns that saw the expansion of his kingdom. King Ashoka sent his son Mahindra to Sri Lanka to invite his contemporary King Devanampiyatissa to accept Buddhism, which he did very gladly. After the king accepted Buddhism his subjects followed suit, and Sri Lanka became a mainly Buddhist country thereafter and remains so up to this day.

The narrator in his enthusiasm to extol the virtues of the King and portray him as a pious Buddhist, ascribes several miraculous happenings during his consecration. However, the narrative has great significance for the history of jewels and jewelry in Sri Lanka and the rest of the world. It clearly brings out the fact that the three main types of precious stones in Sri Lanka since ancient times, had been sapphires, beryls and rubies, apart from the organic gems - the pearls, obtained from the sea. The fact that the gifts impressed the mighty king Ashoka to the extent that he bestowed special honors and titles on the members of king Devanampiyatissa's delegation, speaks for the high quality of the precious stones and pearls that originated in Sri Lanka at that time.

Evidence from foreign writings of the antiquity of the pearl trade in Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

Pearls and beryls from Sri Lanka mentioned in the Mahabharata, the ancient great Indian epic of the 4th-century B.C.

In the ancient Indian epic the Mahabharata, that is believed to have originated around the 4th-century B.C. mention is made of Sri Lankan pearls, in the second parva or book, known as the Sabha Parva (The Book of the Assembly Hall). The Simhalas of Sri Lanka are said to have offered to the legendary Indian king Yudhisthira, the choicest gifts of the sea, pearls and conches, and also gemstones like beryls(catseyes).

Kautilya, chief adviser and minister to King Chandragupta Maurya refers to the lucrative pearl banks of the Kondaichchi Bay in the Gulf of Mannar, situated near the mouth of the River Kula (Kala Oya), in his book the Arthashastra, written in the 4th-3rd century B.C.

Kautilya, close adviser, political and military strategist and minister to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan kingdom in eastern India, in his book the "Arthashastra" written in the 4th-3rd century B.C. refers to the pearl banks closer to the mouth of the River Kula (Kala Oya) in the Kondaichchi Bay in the Gulf of Mannar, in northwest Sri Lanka. The Arthashastra apart from dealing in politics, statecraft, law and military strategy, also treats extensively the economy of a vibrant state, giving details of economics activities, such as mineralogy, mining and metals, agriculture, animal husbandry, medicine, the use of wildlife, and natural pearl production. In giving an extensive account of the natural pearl production in India, he gives a list of ten different coastal areas in India and Sri Lanka where natural pearl fisheries existed during his time. Of the five areas in southern India he had mentioned, where a natural pearl fishery existed, one area known as "Kula" was in the northwest of Sri Lanka. He was actually referring to the lucrative pearl banks in the Gulf of Mannar, near the mouth of the River Kula (Kala Oya), that flows into the Kondaichchi Bay, below the Island of Mannar.

Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Mauryan king Chandragupta of India writes about Srl Lankan pearls in the 3rd-century B.C.

Sri Lanka was known to the ancient Greeks as "Palaesimoundu" and "Taprobane," and the island of Mannar, the center of the pearl trade was known as "Epidorus." Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the court of the Mauryan King Chandragupta, wrote in the 3rd-century B.C. that, "the island of Taprobane was more productive of gold and large pearls than the Indias."

The Phoenicians, enterprising seafarers reached Epidorus (Mannar) in Sri Lanka to purchase pearls, which they re-sold to the Greeks, Romans and ancient Egyptians

The Phoenicians who were enterprising seafarers and a powerful maritime trading nation in the Mediterranean from 1500 B.C. to 300 B.C. are believed to have reached Epidorus (Mannar) in Sri Lanka to purchase pearls, and these pearls were subsequently sold to the Greeks, Romans and ancient Egyptians.

Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, a Greek book written in the 1st-century A.D. gives an accurate account of the pearl fishery in the Gulf of Mannar, not found even in the "Mahawamsa." However, the account is from the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar, which the ancient Greeks explored during this period.

The Alexandrian-Greek author who wrote the "Periplus of the Erythrean Sea" around the first-century A.D., gives an account of the pearl fishery in the Gulf of Mannar, around the year 60 A.D. The author states that due to the dangers involved in the pearl fishing, it was the usual tradition to employ slaves and convicts, for the difficult task of pearl fishing.

The following is an excerpt from the "Periplus of the Erythrian Sea :-

"Upon leaving Bakare we come to the ruddy mountain towards the south; the country which succeeds is under the Government of Pandian; it is called Paraha and lies almost directly north and south; it reaches to Kolkhoi in the vicinity of the pearl fishery. But, the first port after leaving the Ruddy Mountain is Balita and next to that is Komar (Cape Comorin), which has a good harbour and a village by the shore. From Komar the district extends to Kolkhoi (Korkai) and the pearl fishery which is conducted by slaves or criminals condemned to the service; the whole southern point of the continent is part of Pandiyan's dominion. Beyond Kolkhoi there succeeds another district called the "Coast Country" lying along a gulf (Palk Bay) and has a region inland called Argaru. Here and here only the pearls obtained in the fishery at the island of Epidorus (Mannar) are perforated and prepared for the market, and from the same place are procured the muslins called, Argantic."

A commentary on the above extract from the "Periplus of the Erythrian Sea."

The above account by the unknown Alexandrian-Greek author describes a sea journey undertaken in the first-century A.D. that explored the coastal areas of southern India. It describes the coastal area known as "Paraha," that was occupied by the "Parawa" community, who were by profession fisherman and pearl divers. The account refers to "Kolkhoi," which was "Korkai" the second largest city in the Pandyan kingdom, which was the headquarters of the pearl fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar, as Epidorus (Mannar) was for the Sri Lankan side; the pearl fishery being carried out by slaves and convicted criminals. The city of "Korkai" was situated at the mouth of the river "Tambrapani" a river draining the present district of "Tinnevelly." Due to silting and delta formation, the Korkai harbor was gradually eliminated and the city itself was abandoned and moved closer to the new mouth of the river, before the onset of the medieval period. The new city that sprang up was known as Kayal; Cail by Marcopolo in the 13th-century; and Chayl by the Portuguese in the 16th-century. After further receding of the sea, Kayal was abandoned and the new ports of Kayalpattanam and Pinnakayal (Pinnacoil), occupied by the Moor and Parawa community respectively was created in the early Portuguese period. Mention is also made of "Komar" which is corruption of "Kumari" subsequently anglicized to "Comorin."

An important fact about the drilling of pearls harvested from the pearl fishery in Mannar emerges from the account given in the "Periplus of the Erythrian Sea."

The island of "Epidorus" referred to in the account is the island of Mannar, the headquarters of the pearl fishery on the Sri Lankan side of the Gulf of Mannar. Another important fact that emerges from this accurate account of the pearl fishery of the Gulf of Mannar from the Indian side, by the Greeko-Egyptian geographer, is that all pearls harvested whether from the Sri Lankan side or the Indian side of the Gulf, had to be taken to a place called "Argaru" for drilling and stringing before they are dispatched to the markets. Thus, from this account it appears that in the first-century A.D. all pearls harvested on the Sri Lankan side of the Persian Gulf, were taken to "Argaru" for this purpose.

Ptolemy, the Alexandrian-Roman geographer and astronomer refer to the rich pearl fishing grounds near the Island of Epidorus (Mannar) in Taprobane (Ceylon) in the 2nd-century A.D.

Ptolemy, the 2nd-century A.D. Alexandrian-Roman astronomer and geographer, referred to Sri Lanka as the Island of Taprobane and wrote of the rich pearl fishing grounds near the Island of Epidorus (Mannar), and also about the variety of gemstones found in abundance in the Island, of which the most famous were the beryls, rubies and sapphires.

Ptolemy

Pliny, the Elder, refers to the Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery as the most productive of all fisheries in the world

The Ceylon pearl fishery flourished during the ancient Roman period during which pearls became very popular among the aristocracy of Rome, from around 100 B.C. to around 100 A.D. Pearls from the Gulf of Mannar were highly valued in Rome, and reached Rome, either by Greek and Roman ships that chartered the Indian Ocean or by caravans that took 1-2 years for the long journey. Pliny, the Elder, in the first-century A.D. refers to the Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery as the most productive of all fisheries from different parts of the world, in his famous book "Historia Naturalis."

Pliny the elder- Roman historian

Strabo, the Greek traveler and Geographer of the 1st-century B.C/1st-century A.D. reports on the trans-Indian Ocean trade between the Roman empire and India and Sri Lanka, that also included pearls originating from the Gulf of Mannar

Strabo, the Greek traveler, historian, geographer and philosopher, born in the wealthy kingdom of Pontus, Asia Minor, (presently in Turkey), in 64/63 B.C. traveled to Egypt around 25-24 B.C. during the reign of Augustus Caesar (27 B.C. - 14 A.D.). During this period there was a thriving trans-Indian Ocean trade between the Roman empire and the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka, using vessels making use of seasonal monsoon winds, that lasted from 1st-century B.C. to 4th-century A.D. Strabo reported in his 17-volume work "Geographica" that was written before he died in 24 A.D., that in the year 25-24 B.C. while he was in Egypt he found that around 120 vessels were employed in the trans-Indian Ocean trade between the Roman empire and India and Sri Lanka, originating from Myos Hormos, the Roman port on the western shores of the Red Sea. Around the time Strabo was in Egypt (25-24 B.C.), an Indian embassy arrived that was on its way to visit Octavian Augustus. The embassy carried several gifts to the emperor that included a collection of pearls. One of the embassies that came was from the ruler of the South Indian Pandyan kingdom, who was known in Greek as king Porus or Pandion. The Pandyan kingdom was an important producer of pearls at that time, controlling the pearl banks on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar. Out of the emperors who ruled the Roman empire from 14 A.D. to 361 A.D. nine emperors are believed to have received embassies from India or Sri Lanka. At least two of these embassies were from Sri Lanka, one sent by the Sri Lankan king Sandmukha Siva or Sandamuhune in 50 A.D. to the court of Claudius Caesar (41-54 A.D.) as reported by the Roman historian Pliny, and the other by king Upatissa in the period 361-363 A.D. to the court of emperor Julian, as reported by Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus. As was the tradition during that period all embassies from India and Sri Lanka carried valuable gifts to the Roman emperor, that also included pearls highly valued by the Romans.

A significant portion of the trans-Indian Ocean trade included pearls that was considered to be more valuable than gold at that time

According to Pliny, the Roman empires eastern trade with India and other eastern nations, accounted for 50% of the annual trade of the empire, which he calculated to be around 50 million sesterces. A significant portion of this trade was on pearls, a commodity highly valued in Rome, considered to be more expensive than gold, which according to historians were used together with gold to underpin the Roman monetary system. The trade lasted for about 75 years, up to the death of Nero in 68 A.D. after which there was a steady decline in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. and then again a recovery in the 4th-century A.D. The trade with the south Indian Pandyan kingdom, was a significant portion of this annual trade, and consisted of commodities that were in greatest demand, such as spices, pepper, ivory, ebony, sandalwood, muslin, precious stones and pearls. According to pliny, these commodities were sold in Rome, at one hundred times their initial cost.

The discovery of Roman pottery and coins at several coastal locations in India and Sri Lanka, and whole pearls and drilled pearls excavated from Mantai (Mahatittha) near Mannar, the main port of Sri Lanka at that time, confirms the thriving trade in pearls originating in the Gulf of Mannar, during the period of the Roman empire.

The discovery of Roman pottery and coins in the coastal cities and ports in southern India and northwestern Sri Lanka confirms the extensive trade contacts between Rome and India and Sri Lanka. The areas from where Roman pottery and coins were discovered in Sri Lanka, were Attikuli in the Mannar district and Kantarodni on the Jaffna Peninsula, both important areas of pearl fishing during this period. However, the main port city in Sri Lanka during this period was the ancient port of Mantai or Mahatittha near Mannar from which Sri Lankan products such as spices, ivory, gemstones and pearls were exported, a port city that was indicated in Ptolemy's map of Sri Lanka. Excavations around Mantai have led to the discovery of whole and drilled pearls, that confirms pearls were among the commodities exported from that port, situated closer to the pearl banks on the Sri Lankan side.

Alexandrian merchant Cosmas Indicopleustus reports in the 6th-century A.D. that Sri Lanka was a great international trade mart frequented by ships from many nations, such as India, Persia, Ethiopia and the Roman empire.

In the 6th-century A.D. the Alexandrian merchant Cosmas Indicopleustus reported that the island of Taprobane (Sri Lanka), was a great trade mart, much frequented by ships from all parts of India, Persia and Ethiopia, and it likewise sent out many ships of its own. Most of the products of Sri Lanka that reached the west during the early period of the Christian era, such as pearls, gemstones, ivory, spices etc. were sent out directly from the island, from the ancient port of Mantai (Mahatittha) or were dispatched to the Malabar coast from where they were picked up by Roman ships, Malabar serving as a trans-shipment point.

6th-century A.D. gemological text, "Ratnapariksa" (Examination of Gems) by Buddhabhatta, makes reference to the quality of Ceylon pearls

Buddhabatta's 6th-century gemological text, the Ratnapariksa (Examination of Gems), makes reference to Sri Lankan pearls and their quality in verses 75 and 76. In verse 75, Sri Lanka is mentioned as one of six sources of pearls in the known world at that time, the others being Paraloka, Surastra, Tamraparni, Pundra and the Himalayas. In verse 76, more sources of pearls are mentioned including Sri Lanka, but these sources are singled out as producing pearls of a certain quality, color, size and shape. These other sources are Barbara in Persia, Aravati and Kontara.

Emerson Tennent's viewpoint that King Solomon in the 10th-century B.C. sent his ships to the seaports of Sri Lanka to purchase precious stones, pearls, ivory, apes and peacocks

The English Historian James Emerson Tennent theorized in his publication on Ceylon, Vol I in 1859, that the natural harbor in Galle, a city in Southern Sri Lanka, on the international east-west shipping route, was the ancient seaport of Tarshish, reached by King Solomon's ships in the 10th-century B.C. from where they obtained precious stones such as rubies, sapphires and beryls; pearls harvested from the pearl banks closer to Mannar; and ivory, apes and peacocks found abundantly in the Island. However, there is no archeological evidence to support his theory.

According to Charles Stuart Pratt, the Romans sent caravans on year-long journeys to Ceylon, for the specific purpose of purchasing pearls

In the July 1896 issue of the monthly magazine "Popular Science" published by the Bonnier Corporation, Charles Stuart Pratt, writing an article titled "Pearls and Mother of Pearl" makes an almost prophetic prediction of the future success of culturing pearls in "oyster ranches" set up for the purpose in a suitable marine environment such as the southern California coast, in which oysters could be induced to produce pearls by artificially seeding them with alien particles such as grains of sand or other material as nucleus of the pearl. Perhaps, Charles Stuart Pratt was already aware of the partial success achieved by Mikimoto in Japan in 1893, when he was able to culture a hemispherical pearl known as a "mabe" pearl, after extensive research on the culturing of Akoya pearls in his oyster farm in the Shinmei inlet on Ago bay, and it was only a matter of time before a technique for culturing whole spherical pearls was developed. In this same article Pratt writing about the history of the appreciation of pearls, states that ancient Romans sent caravans on year-long journeys to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), for the specific purpose of purchasing pearls.

According to James Hornell, the marine biologist to the Colonial Government of Ceylon, the Gulf of Mannar Pearl Fishery was the world's greatest, that none can compare in terms of its antiquity as well as continuity of exploitation

An article written by James Hornell, the marine biologist to the Ceylon Colonial Government, titled "The Pearl Fishery" and published in the book "Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon" by Arnold Wright, describes the Pearl Fishery of the Gulf of Mannar as "the world's greatest fisheries, that none can compare either in point of antiquity or in the continuity of their prosecution, with the portion belonging to Ceylon being the more lucrative and famous ( as opposed to fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf). Continuing further he says that, "Three thousand years ago the Tamil Kings of Southern India reckoned this fishery one of the principal sources of their large revenues, so much so that the chief of the pearling centers was second only to Madura, the capital, and was the residence of the heir apparent.

According to James Hornell a gift of pearls by King Vijaya to his father-in-law the Pandyan king of Madura, bespeaks of a settled fishery for pearls on the coasts of his domain

The pearl banks of Ceylon came into historic ken rather later - not, indeed, till the 6th-century before Christ, a fact due rather to the absence of all historical data prior to the Aryan conquest of the island about 550 B.C. than to their non-existence. A gift of pearls by Vijaya, the leader of the invaders and the first Sinhalese king of Ceylon, to his father-in-law the Pandyan king of Madura, is duly set down with a list of other essentially Ceylon products in the Mahawansa, the Royal chronicle of the Sinhalese. Such a gift bespeaks a settled fishery for pearls on the coast of his dominions, undoubtedly carried on by men of Tamil race, even as is the case today in large part; the Sinhalese themselves have never taken to this industry, their instincts being largely, if not exclusively agricultural.

Historic references to the pearl fishery are common only after the dawn of the Christian era

From the dawn of our own era (Christian era), historic references become frequent. In Rome in the days of Pliny, pearls from the Gulf of Mannar were valued at a high price, and Pliny himself refers to this fishery as the most productive of pearls in all the world. Ptolemy and the unknown author of the "Periplus of the Erythrian Sea" both knew its location well, and the latter gave definite sailing directions for the use of mariners navigating the gulf.

But, it would take too long to recount all that adventurous Greeks, Barbary Moors, Venetians and Genoese have jotted down of the wonders of the pearl harvest of these seas, in the centuries immediately preceding the arrival of Vasco da Gama off the Indian coast.

A commentary on James Hornell's observations

James Hornell's estimation that the pearl fishery of the Gulf of Mannar was the world's greatest, was a reiteration of what Pliny said 2,000 years ago, that this pearl fishery was the most productive of all fisheries from different parts of the world. However, according to Hornell, the Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery is also the oldest pearl fishery in the world, that had been worked for a longer period of time than any other fishery. As a British marine biologist who had been involved in studying the pearl banks on both sides of the Gulf of Mannar, and having first hand knowledge of the quantity of oysters harvested on both sides as well as the revenue accruing to the governments on both sides, his assertion that the pearl banks belonging to Ceylon was more lucrative than the pearl banks on the Indian side, must be quite accurate. Yet, the pearl banks on the Indian side 2,000 to 3,000 years ago provided large revenues to the Pandyan kings of Madura, that the headquarters of the pearl fishery, the city of "Korkai" was considered the second most important city in the Pandyan kingdom after the capital Madurai, that deserved to be the residence of the heir apparent.

Even though recorded historical evidence of the existence of the pearl fishery in the Gulf of Mannar, begins only with the mid 6th-century B.C. James Hornell is convinced of the antiquity of the pearl fishery, that must have existed long before this period. But, how long before the mid 6th-century B.C. is a matter of conjecture. This is due to the absence of historical data, including archaeological evidence, prior to 550 B.C. However, the lack of such data does not mean that fishery did not exist prior to the 6th-century B.C. The fact that King Vijaya was able to send a gift of pearls to his father-in-law soon after he settled in Sri Lanka in the mid 6th-century B.C. provides indirect evidence for the existence of an established fishery at the time he landed in Sri Lanka with his 700 followers. James Hornell also asserts that the pearl fishery on the Sri Lankan side of the Gulf of Mannar, was worked by the men of the Tamil race, and the Sinhalese were never involved in the exploitation of the pearl resources, being mainly farmers by profession. Even among the Tamils only coastal dwellers, such as fishermen and boatmen, known as "karaiyar' served as pearl divers. The people of the Tamil speaking parawa caste of southern India, were the main pearl divers of the region, before the Moors, the descendants of Arab settlers in the region, also took a keen interest in pearl diving, as their Arab ancestors. At the time Vijaya and his followers landed in the northwest coast of Sri Lanka, closer to the pearl fishing region of the country, one of the indigenous tribes that lived in Sri Lanka was the "Nagas," who according to some Tamil historians were the ancestors of the parawas. Thus, it was quite possible that during the time of king Vijaya, it was the "Nagas" who served as pearl divers, and these Nagas of Sri Lanka at the time of Vijaya's landing spoke the local Elu language apart from Tamil, due to the regional influence of southern India. The indigenous tribes of Sri Lanka, at the time of Vijaya's landing, the Yakkas and the Nagas spoke the local Elu language, which subsequently merged with the Parakrit of the Indo-Aryans to produce the language known as Sinhala, that became the mother tongue of the Sinhalese, the largest ethnic group of Sri Lanka

According to Periplus of the Erythrian Sea, pearls harvested from the Gulf of Mannar were superior in quality to that of the Persian Gulf

The Periplus of the Erythrian Sea records that Apologos (Uballah in Arabic), situated at the mouth of the Euphrates, and Omana at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, sent large quantities of pearls, though inferior to the Indian pearls (pearls from the Gulf of Mannar), to Arabia and Barygaza (Broach), the emporium in northwest India, referred to by Ptolemy. The above comment in the Periplus, brings out two important facts in the ancient international pearl trade :-

1) That the pearls harvested from the Gulf of Mannar were superior in quality to the pearls harvested from the Persian Gulf.

2) That the export of pearls from the Persian Gulf to northern India was of ancient origin, dating back probably to the period 1st-century B.C./1st-century A.D. Subsequently, during the medieval and modern periods, pearls from Persian Gulf reached Bombay the main emporium of oriental pearls in the world, from where they found their way to the pearl markets of the world.

Evidence for the antiquity of appreciation of pearls and the pearl industry and trade in India

Archaeological evidence for the use of pearls in India during pre-historic and early historic times are lacking, but compensated by textual evidence from very ancient literature dating back to around 3,700 B.P.

Unlike the Persian Gulf region, archaeological evidence for the use of pearls in India in pre-historic times, or the early historic period are very scarce or virtually non-existent. According to R.A. Donkin's book "Beyond Price, Pearls and Pearl Fishing" there are very few ancient pearls and none that antedates the rise of Buddhism around 500 B.C. However, what is lacking in archaeological evidence appears to be more than compensated by the availability of an enormous volume of ancient literature, mentioning the use and appreciation of pearls, the oldest dating back to around 1,700-1,100 B.C. (3,700-3,100 B.P), such as the Vedas, Brahmanas, Puranas, and the two great epic poems the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and the renowned treatise on political science and economics of the 4th-century B.C. known as "Arthasastra" written by Kautilya, that gives details of the centers of pearl fishing in India during that period, the first of its kind from anywhere in the world.

There is no archaeological evidence for the use of pearls in the ancient civilization of the Indus Valley, but some mother-of-pearl beads and other shell beads from univalve mollusks like sea-snails have been uncovered

The most ancient civilization of India, is the Indus Valley Civilization, a bronze-age civilization dating back from 3,300 to 1,300 B.C.E. (5,300-3,300 B.P.), which is as old as some of the Mesopotamian civilizations. The mature phase of the Indus Valley civilization is known as the Harappa civilization, that lasted from 2,600-1,900 B.C.E. The Indus Valley Civilization was situated in most of present-day Pakistan, extending from Baluchistan to Sindh, and into the modern-day Indian States of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab. Mohenjo-daro was one of the largest urban settlements of the Indus Valley Civilization, built around 2,600 B.C.E. presently situated in the Larkana District of Sindh in modern-day Pakistan. Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and other IVC settlements have yielded evidence of a sophisticated jewelry industry, turning out personal jewelry, that incorporated beads made out of a wide range of materials, such as gold, silver, copper, lapis-lazuli, agate, jasper, cornelian, turquoise, steatite, hematite, shell, ivory and bone. Pearl beads have not been recovered from these sites, or might not have survived the ravages of time. However, evidence have emerged that Harappa civilization established trade contacts with ancient Mesopotamian civilizations of the Persian Gulf region, and among the items believed to be traded were pearls, beads of different materials listed above, copper, ivory etc. in exchange for Mesopotamian wool, leather and olive oil. Some mother-of-pearl beads were excavated from Mohenjo-daro, and another IVC settlement known as Chanhu-daro. Other shell beads and shell inlay recovered appear to have been derived from the shell of univalve mollusks, sea-snails such as Turbinella species (sacred chank shell) and Fasciolaria species (tulip shell). Coral items derived from the head-coral. Favia fabus have also appeared.

Archaeological pearls discovered from Taxila at Bhir, only date back to around 300-200 B.C. (2,300-2,200 B.P.).

Taxila was an important Hindu and Buddhist center of learning belonging to the Gandhara period, and presently located in the Punjab province of Pakistan, 32 km northwest of Islamabad. Taxila, with its capital at Bhir, was situated at the crossroads of three major trade routes, in northwestern India, and hence came under the influence of foreign invaders; first by DariusI in 518 B.C., who annexed Taxila to the Persian Archaemenid Empire and later in 326 B.C. by Alexander the Great, and in 321 B.C. by Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan empire in eastern India, who expanded his kingdom to include northern and northwestern India. Emperor Chandragupta himself was a student at Taxila when it was a seat of Vedic learning, and so was his closest advisor and strategist Chanakya, also known as Kautilya, who is said to have written the renowned treatise on political science and economics while being a teacher in the great halls of learning of Taxila. Another distinguished alumnus of Taxila was the famous Ayurvedic healer Charaka. During the reign of king Ashoka, the grandson of king Chandragupta, who embraced Buddhism, Taxila under royal patronage became a great Buddhist center of learning. After the fall of the Mauryan empire, in 185 B.C. Taxila came under Bactrian Greek rule, and the Indo-Greeks built a new capital city at Sirkap. The Indo-Greek rulers were ousted by Indo-Scythian rulers in 90 B.C. who in turn were ousted by the Indo-Parthian rulers in 20 B.C. In 76 A.D. the Kushana kings took control of Taxila, who built a new capital at Sirsukh. During the period 460-470 A.D. (5th-century A.D.) the marauding armies of the Hepthalites, swept over Gandhara and Punjab, causing total devastation of Taxila and the destruction of its ancient Buddhist monasteries and stupas, from which Taxila never recovered, and the ruined city was eventually buried in mounds of earth.

The three former capital cities of Taxila, Bhir from the 6th-century B.C., Sirkap from the 2nd-century B.C. and Sirsukh from the 1st-century A.D. are the three main archaeological sites that have been excavated and restored today. During the excavations of Bhir, the oldest of the Taxila sites, mother-of-pearl, small pearls and corals were discovered. However, the pearls discovered came from the upper strata of the mound, and may not be older than 300-200 B.C. Pearls of later date, probably 1st-century B.C/1st-century A.D. were discovered from Sirkap, and the ones from Sirsukh were from 1st/2nd century A.D. Pearls older than the ones discovered in Bhir, have not been reported from any part of India. Pearls identified on terracotta figurines from Ahicchattra, the ancient fortress city near Bareilly, believed to have been visited by the Buddha, dates from around 300 B.C.

Evidence from ancient sacred Hindu texts and literature

Evidence from the Vedas

The Aryans invaded northern India around 2,000 B.C. through the passes of the Hindu-Kush mountain range extending from northwestern Pakistan and eastern and central Afghanistan. It is believed that the invasion of the Aryans from the steppes of Central Asia was probably responsible for the decline and fall of the ancient Harappa civilization. The Aryans came with their culture and beliefs that eventually evolved into Hinduism or the Vedic culture, the oldest living religion in the world. The scriptures of the Hindu religion are written in Sanskrit and the most ancient of these scriptures are the Vedas. There are four Vedas :- Rigveda, Samaveda, Yagusveda and Atharvaveda. The Rigveda is the oldest, believed to have originated around 1,700-1,100 B.C. Each Veda is divided into 4 parts : the Samhita, the Veda proper in verse form, consisting of sacred mantras, and the other three consisting of commentaries in prose form, known as the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads. The peoples, places and events described in the Rigveda relate almost exclusively to northern India, and especially to the Punjab. The Atharvaveda, the 4th-Veda originating from 1,200 - 1,000 B.C. incorporates the early traditions of medicine, healing and magic, and identifies the causes of disease as living causative agents, seeking to kill them by a combination of plant-based drugs and magical incantations.

There are many instances of reference to pearls both in the Rigveda and the Atharvaveda, the term used for pearls being "krisana," In later Sanskrit works, the term "krisana" is replaced by "muktha" which is of Dravidian origin. According to the Rigveda, krisanas were used to decorate horses and chariots or sacred wagons. The Satapatha Brahmana mentions of golden pearls woven into the manes and tails of sacrificial horses. Thus, the Rigveda shows that pearls were highly valued and had symbolic significance in northwest India in the 2nd-millennium B.C.

According to the Atharvaveda, the pearl and its shell serves as an amulet, that ensures long life and protects against all evils, such as disease, demons, poverty etc. Considered as the "bone of gods" and described as "one of the golden substances," pearls are said to be the net result of the elements of nature working in consonance with one another, such as the sea, rivers, wind, lightning, the clouds, heavens and the moon. Around 500 B.C. the pearl was an integral part of Aryan symbolism and sacred ritual, which according to R.A. Donkin was a result of the long familiarity with pearls over several millennia, perhaps extending to Proto-Aryan times in Central Asia.

Evidence from the Manusmriti - the Laws of Manu

The Manusmriti or the Laws of Manu, is believed by followers of Hinduism to be a revealed scripture (Smriti) by Lord Brahma himself, the creator, to his son Manu, prescribing the norms of domestic, social and religious life of Hindus, the duties and responsibilities of rulers, the modus operandi in civil and criminal proceedings and punishments to be meted out, laws of ownership of property and inheritance, divorce and lawful occupations of each caste, the kind of penance for misdeeds, and the concept of karma, rebirth and salvation. The scripture comprises of 2,684 verses, that are divided into twelve chapters. The origin of the scriptures are believed to date back from 1,200 B.C. to around 500 B.C. In one of the verses dealing with penalties for theft, pearls are distinguished from corals and other gemstones including rubies. The fact that pearls are listed among valuable items of jewels and jewelry, clearly indicate the usage and appreciation of pearls among the ancient followers of Hinduism in India during the period 1,200 B.C. to 500 B.C.

Evidence from the Puranas

Puranas are ancient oral traditions, and legends that existed as narratives or stories from time immemorial, concerning the history of the universe from creation to destruction, genealogies of kings, heroes, sages and demigods, and descriptions of Hindu cosmology, philosophy, and geography, that were subsequently converted to a written form during the Gupta period from 3rd to 5th century A.D. The most important of the Puranas are the Mahapuranas (Great Puranas), consisting of 18 Puranas. consisting of a minimum of 9,000 verses in the Markendaya Purana to a maximum of 81,100 verses in the Skanda Purana. In the Varaha Purana consisting of 10,000 verses, one of the verses relate how a merchant embarked on a voyage in a sea-going vessel in quest of pearls with people who knew all about them. Markandeya Purana, the shortest Mahaprurana relating the origin of the Goddess C'andika, states that the "Ocean of Milk" gave a spotless necklace of pearls. Again reference to pearls are made in the Agni Purana (15,400 verses) and the Garuda Purana (19,000 verses), treating the origins of different kinds of "pearls" both real pearls originating from the oysters and conch shells, as well as "pearls" originating from elephants, wild boars, whales, fish, cobras and in the stems of bamboos, some of which were renowned as amulets as the serpent pearls.

Evidence from the two great epics of ancient India, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata

The Ramayana ascribed to the Hindu sage Valmiki possibly originated in the 5th-4th century B.C.

The Ramayana and Mahabharata are the two great and ancient Sanskrit epics of India. The Ramayana ascribed to the Hindu sage Valmiki forms an important part of the Hindu canon, that brings out the duties and relationships of ideal characters in society, such as the ideal king, ideal wife, ideal brother and ideal servant. The Ramayana consisting of 24,000 verses, in seven books (kandas) and 500 cantos (sargas), tells the story of Rama, an incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, whose wife Sita is abducted by the demon king of Lanka, Ravana. Thematically, the epic explores the tenets of human existence and the concept of dharma. Historians have suggested the possible period of origin of the Ramayana as between the 5th-4th century B.C.

The Mahabaratha, ascribed to Vyasa, is the world's second largest book whose origins go back to the 4th-century B.C. but was compiled as a sacred text around 350 A.D.

The Mahabaratha, which is four times the length of the Ramayana, consisting of over 100,000 verses is considered as part of Hindu "itihasa" (history), and is ascribed to the author Vyasa. It is probably the world's second largest book, after the Gesar epic of Tibet. The origin of the Mahabharata is believed to be around the 4th-century B.C. and existed as oral traditions passed down from generation to generation, that was compiled around 350 A.D. into a sacred text of 100,000 stanzas, written in Sanskrit. The main story of the Mahabharata is the bitter rivalry that develops between the five sons of the deceased king Pandu, known as the Pandavas, and their cousins, the 100 sons of the blind king Dhritarashtra, known as the Kauravas, over the possession of the ancestral Bharata kingdom, with its capital city in Hastinapura, on the Ganga river, in north-central India, that leads to a fratricidal war, known as the Kurukushetra war. Incorporated into the epic narrative are philosophcal and devotional material, such as a discussion on the four goals of human life - dharma (right action), artha (purpose), kama (pleasure) and moksha(liberation). Other works and stories associated with the Mahabharata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, an abbreviated version of the Ramayana and the Rishyasringa, which are works in their own right.

Both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata make several references to pearls in their texts. The Mahabharata is divided into 18 parvas or books, of which the second parva is the Sabha Parva - The book of the Assembly Hall, in which reference is made to the Simhalas (Sri Lankans) who are said to have offered to Yudhishthira, the eldest of the Pandavas and the rightful heir to the throne, the choicest gifts of the seas, pearls and conchs, as well as beryls (cat's-eyes).

Kautilya's Arthashastra, a book on political science, law, economics and military strategy, written around 4th-century B.C. provides the strongest evidence of the antiquity of the pearl fisheries in India, giving a list of prominent pearl fisheries both in India and neighboring Sri Lanka

Kautilya is believed to have written the "Arthashastra" while he was a teacher in the great seat of Vedic learning, Taxila

The Arthashastra, variously translated as "Science of Politics," "Treatise on Polity," "Science on Material Gain," etc. is a comprehensive and controversial ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, law, economic policy and military strategy, ascribed to the 4th-3rd century B.C. Brahmin intellectual Kautilya, also known as Vishnugupta or Chanakya, an eminent scholar and alumnus of the great seat of Vedic learning, Taxila in northwestern India, who was subsequently appointed as a close adviser, political and military strategist and minister to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan kingdom in eastern India. Kautilya is believed to have written his renowned treatise on political science and economics while being a teacher in the great halls of learning at Taxila, and Emperor Chandragupta who studied in the same Vedic schools, was a probably a student of Kautilya.

Kautilya's views on statecraft was meant for a monarchy or an autocratic ruler, but he clearly advocated a people-centered form of governance

Kautilya's treatise discusses theories and principles of governing a state ruled by a monarchy or an autocratic ruler, and may not be applicable in the modern context of democracy and republican form of government. Yet his treatise have a significance in a historical context as it shows how statecraft evolved from autocratic monarchial forms of government to the modern republican form of government. Kautilya, the political scientist, who lived over 2,300 years ago, has shown clearly that in whatever form of government, the ultimate beneficiaries should be the people. He says in his treatise, "The sacred task of a king is to strive for the welfare of his people incessantly. The administration of the kingdom is his religious duty. His greatest gift would be to treat all as equals." He goes on further on the people-centered form of governance, "The happiness of the commoners is the happiness of the king. Their welfare is his welfare. A king should never think of his personal interest or welfare, but should ever try to find his joy in the joy of his subjects."

He discusses the duties of a king extensively in Book I, Chapter 19. to the extent that he recommends a time-table to be followed by would-be king, in which due prominence is given to public audiences, to hear petitions and look into to the problems of the people.

When in his court he shall never cause his petitioners to wait at the door, for when a king makes himself inaccessible to his people and entrusts his work to his immediate officers, he may be sure to engender confusion in business, and to cause thereby public disaffection, and himself a prey to his enemies. He shall, therefore, personally attend to the business of gods, of heretics, of Brahmans learned in the Vedas, of cattle, of sacred places, of minors, the aged, the afflicted, and the helpless, and of women; all this in order (of enumeration) or according to the urgency or pressure of those works. All urgent calls he shall hear at once, but never put off, for when postponed, they will prove too hard or impossible to accomplish.

These are some of the sublime thoughts of a great intellectual of the 4th-century B.C. which are even applicable today in the governance of the modern democratic state by leaders elected by the people.

Doubts have been cast on whether an individual capable of sublime thoughts as a people-centered governance would at the same time advocate violence as a means of perpetuating oneself in power

However, Kautilya's book was mainly intended as a guidance to kings and emperors, as this was the form of government prevalent during his time all over the world. While writing extensively of the duties of a king, he also gives guidelines of what a king should do to protect his position and power, from enemies, both external as well as internal from his own family. However, some of the methods he has suggested such as espionage, the use of provocative agents, murder, false accusations etc. without any ethical considerations may sound revolting to the modern political scientist. Doubts have been cast on whether an intellectual capable of such sublime thoughts as outlined above, may at the same time advocate violence as a means of perpetuating oneself in power. Some of the more revolting sections in the Arthashastra as it is known today, may not not have flowed from the pen of the celebrated author himself, as it has been convincingly proved by historians, based on the numerous stylistic and linguistic variations, belonging to different periods, that other authors were also involved, who would have perhaps revised and expanded the treatise.

The treatise also deals extensively on economic policies of a vibrant state, and discusses economic activities including natural pearl production

Apart from statecraft, military strategy, laws governing social institutions and punishment prescribed for violation of these laws and other criminal offences, the treatise also deals extensively on economic policies of a vibrant state, and discusses economic activities, such as mineralogy, mining and metals, agriculture, animal husbandry, medicine, the use of wildlife, and natural pearl production. Pearls were highly valued in India at that time, valued more than gold, and used exclusively by members of the royalty, or sold to other countries such as Greece and Rome, or countries of the Persian Gulf. Kautilya's account of the natural pearl industry in India is accepted by jewelry historians as a reliable guide to areas of pearl production in India around the time of Alexander the Great's invasion in 326-325 B.C. The areas of pearl production in India in the 4th-century B.C. mentioned in the treatise, is confirmed by accounts given by later authorities on the subject.

Details given by Kautilya such as the areas of pearl production in India, properties of good and bad quality pearls, and the types of ornaments in which pearls are incorporated provides the strongest evidence for the antiquity of the pearl industry in India, that might go back to at least one millennium B.C.

Thus, according to information provided by Kautilya on the status of the natural pearl industry in India, it appears that the industry had been on-going in India during the greater part of the 1st-millennium B.C. or even before. In Chapter XI, section 29, Kautilya examines the precious articles to be received into the treasury, and pearls occupy first place in the list. Kautilya, mentions only oysters and conches as sources of origin of pearls. Unlike other ancient and medieval authors, he does not advance any mythological or supernatural explanations for the origin of pearls. He describes in detail the properties of good quality pearls, as well as defective specimens. He also gives the names and details of different personal ornaments and settings in which pearls are incorporated. The nomenclature used by Kautilya, and the evident technical expertise, undoubtedly shows that pearls had been known and appreciated over a long period of time, before Kautilya's period in the 4th-3rd century B.C.

The 10 areas in ancient India that produced pearls

Kautilya refers to 10 areas in ancient India, that produced pearls. He uses names of rivers to refer to these areas, and pearls were harvested from the sea around the mouth of these rivers. Five of these 10 areas were in southern India and Sri Lanka, mainly in the Gulf of Mannar, one area was in the coast of eastern India, and four in the northwest of India.

The five pearl-producing areas in southern India and Sri Lanka

The five pearl producing areas in southern India were :- 1) Tambraparni 2) Pandyaka-vata 3) Pasika 4) Kula 5) Curni.

1) Tambraparni :- Tambraparni is a river in Tamil Nadu, southern India arising from the Annamalai range on the eastern slopes of the western Ghats, 1,500 meters above sea-level, flowing east through the Tirunelveli and Tuticorin district of Tamil Nadu, and entering the Gulf of Mannar near Punnaikayal. In the 1st-century A.D. the mouth of the Tambraparni was situated inland closer to Korkai, which was the second largest city in the Pandyan kingdom, and the center of the pearl fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar. Subsequently due to silting, delta formation and the receding of the sea, the mouth of the river moved to Kayal from around 8th-century A.D. to around 13th-century A.D. The sea receded further and by early 16th-century, a new city was established at the mouth of the river, known as Pinnakayal (Pinnacoil).

Tambraparni was also the name of the beach near a river in the northwest of Sri Lanka, where Prince Vijaya who led the Indo-Aryan invasion of the Island in the 6th-century B.C, landed. The name Tambraparni is believed to have been derived from the copper-colored, sand on the beach where the Prince and his followers landed, "Tamba" meaning copper. Tambrapani in the northwest coast of Sri Lanka was close to the pearl banks also situated off the northwest coast of the Island.

2) Pandyaka-vata - Pandyaka-vata is the legendary Pandyan Kapatapuram that was situated to the south of the mouth of River Tambraparni. It was actually the terrain between the rivers Kumari and Tambraparni. Kapatapuram was founded by the Pandiyan kings after the ocean deluge, possibly an Indian Ocean Tsunami, that destroyed Tenmaturai and its learned academy of Sanskrit-Tamil Literature. Pandyaka-vata was not only a center of learning, but an important commercial center, visited by foreign merchant ships to buy pearls, ivory, etc. Pandyaka-vata was also close to the pearl banks on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar.

3) Pasika - Pasika is the ancient name for modern Ramnad or Ramnathapuram, in Tamil Nadu, situated near the mouth of river Vaigai. The Vaigai river originates in the Periyar Plateau of the Western Ghats range, and flows northeast through the Kamban Valley, lying between the Palni Hills to the north and the Varushanad Hills to the south. The river then turns southeast, running through the region of Pandya Nadu. Madurai, the capital and largest city of the Pandyan kingdom, was situated on the River Vaigai. The river empties into the Palk Straits in the Ramnathapuram district. Pasika in ancient times was famous as a pearl fishing and selling center.

4) Curni - Curni is the ancient name for River Periyar, in Kerala State, southwest India. The Periyar River originates in the Sivagiri hills of Western Ghats range in Tamil Nadu, 1,830 meters above sea-level. It is the only perennial river in the region, said to be the lifeline of Kerala, providing drinking water to several major cities in Kerala, as well as Tamil Nadu States. The river flows northwards through the Periyar National Park, then northwest and finally eastwards towards the Arabian Sea. Curni, the place where the Periyar River joins the Arabian Sea was famous as a center of pearl fishing in the Arabian Sea, on the eastern coast of Southern India.

5) Kula - Kula is a river in northwest Sri Lanka, flowing into the Gulf of Mannar. Kula probably refers to the Kala Oya, originating in the hills of Matale-Laggala, flowing in the northwest direction and entering the Gulf of Mannar below the island of Mannar, closer to the Kondaichi Bay, where the lucrative pearl banks of Sri Lanka were situated. Thus, Kula refers to the pearl fishery in the pearl banks closer to the mouth of the Kula river (Kala Oya) in northwest Sri Lanka, the most lucrative pearl banks in the Gullf of Mannar.

Pearl producing area in eastern India

Mahendragiri in Orissa - Mahendragiri mentioned in the Arthashastra, is a region and mountain peak in the Eastern Ghats, in Orissa India, between the Godavari and Mahanadi Rivers. A natural pearl fishery existed in this region in ancient times, and pearls originating from the region were known as Orissa pearls.

Pearl producing areas in northwestern India. Kautilya is the only writer from ancient times who mentions about the production of freshwater pearls in ancient India.

Four areas are mentioned in northwestern India, where pearl fisheries existed in ancient times. These are :- 1) Kardama 2) Srotasi 3) Hirda 4) Himavat

1) Kardama - Kardama was a river in northwest India in Uttarapatha or Udichya beyond the Hindu Kush mountain range, a region known as Bactria (Balkh), between the Amu Darya river and the Hindu Kush mountains. Bactria was part of the northeastern territory of the Persian empire. Today the ancient region of Bactria, is divided between Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Kardama being a river in northeast Iran or Afghanistan, pearls produced in this region are undoubtedly freshwater pearls. This is the first record of the production of freshwater pearls in the northwestern borders of the Indian sub-continent.

2) Srotasi - The name Srotasi refers to a distributary in the estuary of the Indus River.

3) Hirda - Hirda is a lake in the estuary of the Indus.

4) Himavat - Himavat was a river flowing from the Himalayas.

The four sources of pearls from northwestern India, mentioned above are either freshwater rivers or lakes. Hence the pearls produced from these sources were most probably freshwater pearls. Kautilya, is the only writer from ancient times who mentions about production of freshwater pearls in India.

"Periplus of the Erythrian Sea" provides the second strongest written evidence for the antiquity of the Indian pearl fishery, after the "Arthashastra" and confirms that the pearl fishery around the mouth of the Tambraparni river was the main pearl fishery of India since ancient times

Extensive accounts of the pearl fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar are given in the Greek book, Periplus of the Erythrian sea written in the 1st-century A.D. by the unknown Alexandrian-Greek author, relevant sections of which were already dealt with under evidences for the antiquity of the Ceylon pearl fishery. The book gives details of all important places connected with the Gulf of Mannar pearl industry, mainly on the Indian side of the Gulf. where the pearl industry in southern India was based, such as Kolkhoi (Korkai), situated at the mouth of the River Tambrapani, the second largest city in the Pandyan kingdom around which the South Indian pearl industry was centered; "Paraha" the coastal belt occupied by the "Parawa" community, who were by profession pearl divers and fisherman; "Komar," Cape Comorin situated at the tip of the Indian sub-continent; Argaru, a city that specializes in the drilling of pearls; and the island of Epidorus (island of Mannar) the main center of the Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery, situated on the Sri Lankan side. The description in the Periplus of the Erythrian Sea, is actually a first hand account of the exploration of the South Indian coastline undertaken by the unknown explorer/author in the 1st-century A.D., one of the renowned coastlines during this period, producing the most precious of all valuables at that time - Pearls. The author not only gives details of the pearl industry of the Gulf of Mannar at that time, but also definite sailing directions for the use of mariners navigating the Gulf of Mannar. The "Periplus of the Erythrian Sea" provides the second strongest written evidence for the antiquity of the Indian pearl industry after the "Arthashastra," and also confirms that the pearl fishery around the mouth of the river "Tambraparni" in southern India, was the main natural pearl fishery of India, listed as the first pearl producing area in the "Arthashastra."

Ptolemy, a Roman-Egyptian author writing about the pearl fishery in the Gulf of Mannar in the 2nd-century A.D., mentions about the karaiyar caste, Tuticorin and Korkai, the center of the pearl fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf

Ptolemy, a Roman-Egyptian (Alexandrian-Roman) geographer, writing about the pearl fishery in the Gulf of Mannar in the 2nd-century A.D. mentions about the towns on the southeastern coast of southern India. "Country of the Kareor; in the Kolkhie Gulf, where there is the pearl fishery, Sosikourai and Kolkhoi, an emporium at the mouth of the river Solen."

Country of the "Kareor" refers to the country of the "karaiyar" (coast people), the caste name for the coast people - fishermen, boatmen and pearl and conch-shell divers. The Paravas (Parathavar) are a section of the "karaiyar" caste. The town Sosikourai refers to Chochikourai or Tuticourai, anglicized later to Tuticorin. "Kolkhoi" refers to "Korkai" the center of the pearl trade, at the mouth of the River Tambrapani. "Kolkhie Gulf" refers to the Gulf of Mannar, and River "Solen" is the name given by the Greeks to "Tambrapani" river.

Strabo's reference to the lucrative trade between the Roman Empire and Pandyan Kingdom in South India, a significant portion of which included pearls harvested from the Gulf of Mannar, confirms the pre-eminent position held by the South Indian kingdom in the international pearl trade, between the 1st-century B.C. and 4th-century A.D.

Strabo, the Greek traveler, and geographer reported in his book "Geographica" written in the early 1st-century A.D. that there was a thriving trans-Indian Ocean trade between the ports of the Roman empire in the Red Sea and the South Indian Pandyan kingdom ruled by king Porus (Pandyan), in which around 120 vessels were employed in 25 B.C. that made use of the seasonal monsoon winds to navigate the Indian Ocean. Items traded included spices, pepper, ivory, ebony, sandalwood, muslin, precious stones and pearls. The trans-Indian Ocean trade according to Pliny accounted for 50% of the annual trade of the Empire, and a significant portion of this trade was on pearls, a commodity highly valued both in India and the Roman Empire, and considered to be more valuable than gold.

South Indian ports that exported pearls according to the Periplus of the Erythrian Sea

Trade and commerce prospered during the early period of the Chera empire from 3rd-century B.C to around 3rd-century A.D. Apart from high quality pearls, other items that were traded and exported from the three main ports of the Chera coast (Kerala coast) of southwest India, Muziris (Cranganur), Nelcynda (Kottayam), and Bacare (Porakad), were precious stones, ivory, tortoise shell, Chinese silk and pepper. For ships originating from Egyptian coast of the Red Sea, during the Roman empire, the season for sailing to these southwest Indian ports, was around the month of July, taking advantage of the southwest monsoon. Even Ptolemy in his "Geographia" mentioned about the three ports of the Chera coast, through which the bulk of the South Indian and some east Asian products reached the Roman empire. The pearls exported to Rome from the Chera ports without any doubt originated from the south Indian or Sri Lankan side of the Gulf of Mannar, or from the southern Coromandel coast on the southeast of India, which was under the domain of the Chola king.

According to the Periplus, pearls that were harvested from the Chola coast (Coromandel coast), were carried to Argalou (Argaru), the market for these pearls, situated some distance inland from the coast, and also the main drilling and stringing center. The markets or collection centers for pearls originating in the Gulf of Mannar, were Colchi emporium (Kolkhoi or Korkai) and Modura Regia (Madurai), the two cities also mentioned by Ptolemy. The only other Indian port, mentioned in the Periplus, from which pearls were said to have been exported was the Ganges, which refers to both the river as well as the town by that name, situated in the Ganges delta in northeastern India. However, pearls harvested from the Ganges river were freshwater pearls.