Open FREE Unlimited Store Join Our Newsletter

Dr. Shihaan M. Larif

Origin of Name

The Abernethy Pearl, a 44-grain extraordinary freshwater pearl discovered in the River Tay in Scotland from a freshwater Unionoidae mussel species known as Margaritifera margaritifera, once common in the rivers of Scotland, gets its name “Abernethy,” as well as its nickname “Little Willie” from William Abernathy, the professional pearl diver who discovered the pearl in 1967. Scotland had been famous for its freshwater pearls since ancient times, and some historians believe that the exceptional quality of these pearls was one of the main reasons that led the Roman Emperor Julius Caesar to invade Britain.

Smeaton’s bridge over River Tay at Perth, Scotland, built in 1771

Attribution: user:kilnburn

Characteristics of the Pearl

The Abernathy Pearl discovered from the freshwater Unionoidae mussel species Margaritifera margaritifera in Scotland is an exceptional pearl in terms of size, shape, color, luster, and surface quality and the combination of all these desirable characteristics have made the pearl one of the most perfect freshwater pearls ever to be discovered not only in Scotland, but perhaps in the whole world, and is therefore listed among the most famous pearls in the world.

For Images of the Abernethy Pearl, Please Click Here (External Link)

In any pearl grading system six basic pearl traits are used in determining the quality and value of pearls. These are, size, shape, color, luster, surface quality and nacre quality.

Size of the pearl

Size of the pearl is one of the crucial factors that determine the quality and value of pearls. Normally larger the size of the pearl greater is its value. In the case of natural pearls size is dependant on the size of the oyster that produced the pearl, the length of time the pearl had grown inside the oyster, climatic and other environmental conditions. However, size is not always associated with quality. Smaller pearls do exist which are of higher quality than larger pearls of poor quality. Size of a pearl is indicated both in terms of its dimensions and weight. Dimensions are given in millimeters and the weight in carats or grains.

The dimension (diameter) of the Abernethy Pearl is not known, but the size of the pearl is said to be comparable to the size of an average marble, which usually has a diameter of about 12.5 mm. The weight of the pearl is 2.2 grams, equivalent to 11 carats or 44 grains. Thus the Abernathy pearl can be considered as a medium sized pearl in comparison to other natural pearls.

Shape of the pearl

Pearls are found in seven basic shapes. These are 1) round 2) near-round 3) oval 4) button 5) drop 6) semi-baroque 7) baroque. The GIA classifies pearl shapes into three main categories. They are :- 1) Spherical 2) Symmetrical and 3) Baroque. Round and near-round pearls come under the spherical category, and have a uniform diameter or nearly uniform diameter all round. Oval, button and drop shapes are considered as symmetrical shapes, and can be divided into two equal halves through a median line. Semi-baroque and baroque are irregular shapes without a line of symmetry and fall under the baroque category.

1) Spherical – round and near-round

2) Symmetrical – oval, button, drop

3) Baroque – semi-baroque and baroque

Among natural freshwater pearls the commonest shape is baroque. Symmetrical shapes are rare; but the rarest of all shapes in freshwater natural pearls is the round shape. The perfectly round shape is the most desired shape for all types of pearls, whether freshwater or saltwater.

The Abernathy pearl has an astoundingly perfect spherical shape, the most desired shape for pearls, but extremely rare in natural freshwater pearls.

Color of the pearl

A pearl’s color is the net effect of three traits, known as hue, overtone and orient. Hue is the overall pearl color that one sees on first impression. Overtone, which may or may not be present is the secondary color associated with the main color, such as pink associated with white known as pinkish-white. The orient or iridescence of a pearl, also not always present, is a colorful rainbow-like sheen caused by the scattering of light by the aragonite platelets in the nacre. Freshwater pearls occur in a wide variety of colors than natural pearls. Some of the colors found in freshwater pearls are white, cream, yellow, pink, rose, lavender, purple, blue, green, brown and red. Common colors found in Scottish freshwater pearls are white, gray, cream, peach and lilac.

The Abernethy pearl is a pinkish-white pearl, with a white hue and a slightly pink overtone.

Luster of the pearl

Luster is the most important of all factors as far as the beauty of a pearl is concerned. Luster is responsible for the so-called inner glow of the pearl, that sets them apart from other gemstones. Luster is a measure of the quality and quantity of light that reflects from the surface and just under the surface of a pearl. It is the reflective quality and brilliance of the surface of the pearl’s nacre. The more lustrous a pearl, the more it shines and reflects light and images. When the luster is low the pearl appears white and chalky and has a matte-like appearance. Generally saltwater pearls tend to have a greater luster than freshwater pearls. Luster is dependant on the thickness and translucency of the nacre. In general thicker the nacre the more lustrous is a pearl. A high quality luster results only when the nacre is translucent and the aragonite plates overlap in such a way that the pearl appears lit from within.

The Abernethy Pearl, in spite of being a freshwater pearl has a striking luster, almost equivalent to the luster of saltwater pearls.

Surface quality

Pearls being creations of nature always have flaws and blemishes on their surface, to the extent that their presence is a proof of their genuineness. A hundred percent blemish-free pearl does not exist. A pearl that appears blemish-free to the naked eye, may still show some blemishes under a magnifying glass or microscope. GIA classifies surface quality into four categories :- 1) Apparently blemish-free or spotless, or contain minor blemishes not visible to the naked eye. 2) Lightly blemished 3) Moderately blemished 4) Heavily blemished.

The Abernathy pearl is apparently blemish-free and without doubt falls under the first category of this classification.

Nacre quality

As mentioned earlier nacre quality is directly related to the luster of the pearl. Nacre quality refers to both the thickness and translucency of the nacre. The depth or thickness of nacre layers can be determined only by inner inspection using optical fibers and soft X-ray apparatus. However careful visual examination might give a rough indication of the quality of the nacre. A dull chalky appearance is usually associated with a thin nacre. In the case of cultured pearls the nacre may be quite thin that even the bead nucleus shows through. A pearl with a good luster is usually associated with a thick translucent nacre.

The Abernethy pearl with its exceptional luster is undoubtedly associated with a naturally created thick translucent nacre.

History of the Abernethy Pearl

History of the exploitation of freshwater mussels in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland

The invasion of Britain by Julius Caesar in 55 BC was prompted by Scottish pearls

The History of the exploitation of the freshwater mussel Margaritifera margaritifera in Britain dates back to over 2,000 years to the pre-Roman period. During the Roman period in 55 BC, one of the four reasons given by Julius Caesar for invading Britain was to take control of the trade in Scottish freshwater pearls, which together with gold, underpinned the Roman monetary system. Historical evidence shows that Roman ships reached as far as the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar to purchase pearls for the royalty in Rome.

Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE)

Commercial exploitation of freshwater mussels in Britain and Ireland

In the 12th century, Scottish pearls were traded in the pearl markets of Europe, and by the 16th century commercial exploitation of the freshwater mussel had developed into a large scale industry in Britain and Ireland. During this period the Government employed river bailiffs to supervise the exploitation of freshwater mussels and to ensure that all valuable pearls reached the King’s treasury. Scottish pearls of exceptional quality entered the crown jewels of both England and Scotland during this period. Some of the monarchs of this period were notorious for adorning themselves with pearls both as jewelry such as multi-strand necklaces, earrings, bracelets etc. and pearl-studded dresses. The famous Armada portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603), gives an indication of the extent to which pearls were valued as adornments by the monarchy, during this period. Another example of the use of pearls by the monarchy is given by the portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587).

Queen Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603) – Armada Portrait

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587)

Small scale exploitation continued into the 20th century, and led to the discovery of the Abernethy pearl in 1967

The commercial exploitation of freshwater mussels in Britain and Ireland continued into the 19th century, but over exploitation without regard to conservation and restoring oyster populations, made the fishery unsustainable, and production declined rapidly and was later abandoned altogether. An interesting parallel is found in the Gulf of Mannar, in Sri Lanka, a source of pearls since very ancient times, which became unsustainable after large scale commercial exploitation by the British Colonialists in Sri Lanka in the 19th century. This is in contrast to what happened in the Persian Gulf, where non-interference by the government in pearling activities was able to sustain small scale pearl fisheries for centuries without any interruption, until the early 20th century, when cultured pearls produced by Mikimoto flooded the international pearl markets.

Small scale pearl fishery by individual pearl divers and the gypsies in Britain and Ireland continued well into the 20th century, until a total ban was imposed on pearl fishing in 1998. It was during this period of small scale pearl fishery, in 1967 that a professional pearl diver by the name of William Abernethy, operating independently, discovered the extremely rare natural freshwater pearl of outstanding qualities, in the River Tay that came to be known as the Abernethy Pearl aka the Little Willie Pearl.

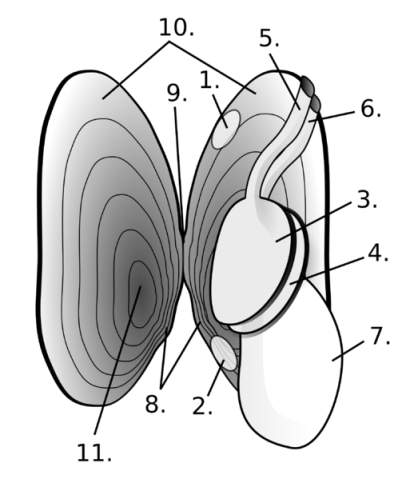

The habitat of the freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera

The freshwater pearl mussels Margaritifera margaritifera inhabit fast-flowing, unpolluted rivers and streams and are normally found buried or partially buried in coarse sand and fine gravel with their siphons exposed. The mussels can rebury themselves if dislodged, and can also move slowly across sandy sediments. The abundant supplies of oxygen found in fast flowing rivers and streams, and suspended food particles are conducive to the growth of the mussels. However development is slow and the young mussels reach maturity only after 10-15 years, when the length of the shell generally exceeds 6.5 cm (65 mm). The growth slows down in older mussels. As the mussels grow annual growth rings are laid down on the shell, like growth rings on tree trunks. By counting the growth rings under a microscope one can estimate the approximate age of the mussels. Using this method scientists have found that the pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera outlives human beings, some individual mussels living up to the age of 140 years, and reaching a maximum shell length of 12-15 cm (120-150 mm). The mussels inhale water through their exposed siphons, and filter out suspended organic particles on which they feed. In waters where large populations of mussels live, the filter feeding process helps to purify the water, that can be beneficial to other species living in the same environment such as the juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown or sea trout (Salmo trutta). It has been estimated that a single mussel can filter up to 50 liters of water in a day.

1. Posterior adductor muscle

2. Anterior adductor muscle

3. Frontal gill

4. Back gill

5. Exhalant aperture

6. Inhalant aperture

7. Foot

8. Pseudotooth

9. The hingeline and ligament

10. Mantle

11. The shell’s thickest part, the umbo

Anatomy of Margaritifera Margaritifera

A collection of live Margaritifera margaritifera- Photo taken from a river bed in SwedenPhoto above ,Creative Commons

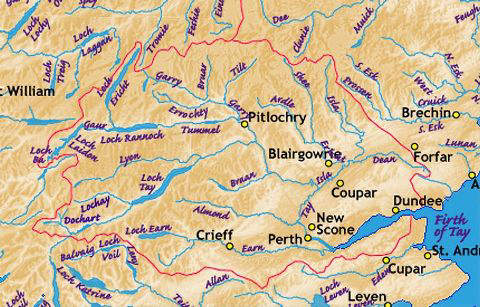

The River Tay, from which the Abernethy Pearl was discovered

Tributaries of River Tay catchment area

The River Tay, which is the longest river in Scotland (120 miles or 193 km), and largest river in the UK in terms of its discharge (170m ³/sec at Perth), originates in the highlands and flows down through Strathtay in the center of Scotland, and then eastwards flowing through Perth and Kinross to the Firth of Tay and the North Sea. The Tay that drains much of the southern highlands, has its source high on the slopes of Ben Lui, just 20 miles (32 km) from the west-coast town of Oban, in Argyll and Bute. Along its course the river assumes different names, known as the River Connonish for the first few miles, then River Fillan and River Dochart, until it flows into Loch Tay at Killin. From Loch Tay the river emerges at Kenmore as River Tay, and flows down to Perth, which in historical times was the lowest bridging point of the river. Downstream of Perth the river becomes tidal and enters the Firth of Tay.

The River Tay where the Abernethy Pearl was discovered by the pearl fisherman William Abernethy, is a fast-moving river, with a discharge of 170m ³/sec at Perth. The turbulent waters of this river, with its falls and rapids along the course of the river from the highlands downstream provides the ideal habitat for the freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera, around which a pearl fishing industry was based since ancient times. The River Tay is also famous for its salmon and trout fishing, two species of fish that serve as intermediate hosts in the completion of the life cycle of Margaritifera margaritifera.

Classification of the freshwater pearl mussel – Margaritifera margaritfera

Kingdom : Animalia

Phylum : Mollusca

Class : Bivalvia

Order : Unionoidae

Family : Margaritiferidae

Genus : Margaritifera

Species : margaritifera

External appearance of the shells of Margritifera margaritifera

Life History of Margritifera margaritifera

Growth and reproduction

The freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera like all other freshwater bivalves are dioecious, i.e. their sexes are separate. The growth of the mussels are slow, and they mature only after 10-15 years. At maturity the length of the mussel exceeds 6.5 cm (65 mm). The mature males shed sperms into the surrounding water in early summer from June to July. The sperms enter the female mussel with the incurrent siphon, and fertilize the eggs, which develop in a pouch on the gills for several weeks. Larvae formed in the fertilized eggs known as glochidia measure 0.6 to 0.7 mm, and are released from July to September. The glochidia resemble tiny mussels, but their shells are held apart until they encounter a suitable host like a juvenile Atlantic salmon or brown trout or sea trout, when the shells snap shut on the hosts gill filaments, thus clinging on to the gills of the host.

The release of glochidia and their attachment to a suitable host

The release of glochidia from the females appear to be a synchronized event taking place over one or two days and influenced by external factors such as a threshold temperature. Each female release between 1 to 4 million glochidia, and in any population of mussels 30-60% of the adult females produce glochidia. For a glochidia to survive it should attach itself to the gills of a suitable host, while it remains viable, which is usually up to six days. The chances of this happening during this period is very remote, in the turbulent conditions of the rivers in which the mussel lives. A majority of the glochidia are swept away by water currents and perish off. However at least a few of them find suitable hosts and are able to survive, thus completing the life cycle. The production of enormous quantities of glochidia is natures way of ensuring that at least a few them would stand the chance of clinging on to a suitable host in the turbulent environmental conditions. The glochidia that successfully attach to the gills of a host get encysted, where it lives and grows in the hyper-oxygenated environment, until the following spring.

Glochidia dropping off from the gills in the following spring and beginning an independent life

In May or early June, the glochidia drop off from the gills, and if they land on clean sandy or gravelly substrates they settle down and begin their independent life. The association between the glochidia and the fish is not harmful to the fish, but ensures the survival of the glochidia and enables young mussels to colonize new areas upstream when the glochidia are dropped after the host fish reaches these areas. The glochidia that are about a mm in length at the time they become independent, initially grow quickly reaching a length of about 4 mm after one year, 12 mm after 3 years, 20 mm after 4 to 5 years and 65 mm at maturity after 10 to 15 years. Thus the average growth per year of the shell is only about 4 mm per year until the shell attains maturity. After this growth slows down and the adult mussel reaches only a maximum of 120 to 150 mm in length in about 80 to 100 years or more. the young mussels are yellowish-brown in color, and as they attain maturity in 10-15 years they become dark brown or black.

Margaritifera margaritifera- Inner surface of shells showing thick layers of nacre

Precarious life cycle of Margaritfera margaritifera that depends on several chance happenings

The life cycle of the freshwater mussels involve huge losses at different stages, such as sperms not reaching a female mussel, the glochidia not reaching a suitable host and glochidia not falling on a suitable substrate from the host. As a result of this precarious life cycle, any adverse conditions to which the mussels are subjected to, can only exacerbate the situation, and threaten the survival of the species. According to Peter Cosgrove, a Scottish-based scientist, an adult female mussel perhaps produces over 200 million glochidia in her lifetime to replace just two adults.

Serious decline of freshwater mussel populations in their holarctic range

The freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera has a holarctic distribution, which include the northern temperate regions of the world, extending from the Arctic and the temperate regions of western Russia, through continental Europe to the northeastern seaboard of North America. Scientists have found a serious decline in the populations of this freshwater mussel species throughout its range, sometimes as high as 95-100%. In many areas of England and Wales where the species was formerly abundant, populations have declined seriously or are virtually extinct. In Northern Ireland, home of the rare hard-water variety of the species known as Margaritifera margaritifera durrovensis, recent research had shown serious decline in populations. In Scotland, one of the regions where the species was most abundant, a recent survey conducted between 1996 and 1999 have shown that the species is now extinct in most of the lowlands, and generally scarce everywhere except in a few highland rivers. Studies have further shown that at the current rates of extinction, the surviving Scottish populations of margaritifera will be totally extinct in a period of 25 years.

Causes for the decline in mussel populations

Some of the early causes of decline in populations were :-

1) Pearl fishing

2) Industrial pollution

Some of the current causes that have been identified are :-

1) Poor water quality

2) Habitat modification or destruction

3) Decline in host fish population

4) Sedimentation or siltation

5) Eutrophication

6) Acidification

7) Amateur pearl fishing

8) Climatic change

Early causes

1) Pearl fishing

Exploitation of freshwater pearl mussels in Scotland and other areas in Britain and Ireland had been taking place for centuries at sustainable levels. However, beginning from the 16th century onwards commercial exploitation was intensified developing into a large scale industry in Britain and Ireland. This exploitation was carried out at unsustainable levels without regard to conservation and restoration of mussel populations, well into the 19th century, and the result was the rapid decrease in populations that spelt the doom of the industry. Restoration of pearl populations to their original levels were delayed, not only because of the slow growth of the pearl mussels, but also due to the long time taken for mussels to attain maturity, which was 10-15 years. In this situation if adult populations that were still fertile were removed, it had disastrous consequences on the entire population. However, small scale pearl fishing by individual pearl divers and the “traveling people” in Scotland continued well into the 20th century, until a total ban was imposed in 1998.

2) Industrial pollution

The spate of industrialization of the 19th and 20th centuries had a drastic effect on the environment, with industrial effluents being discharged into the rivers, and streams, that had a devastating effect on all aquatic life. In the case of the freshwater pearl mussels the effect of the industrial pollutants was more serious than in other species, as mussels were adapted for survival in a highly oxygenated environment, as found in a fast moving river, with their rapids and falls. Polluted waters affected the mussel populations in two ways : 1) By being directly toxic to the mussels 2) By drastically reducing the oxygen content in the water, which was crucial for their survival. Industrial pollution eliminated mussel populations in many rivers, and only those rivers that were untouched by pollution or were marginally affected were able to sustain such populations.

Current causes

1) Poor water quality

Poor water quality caused by industrial effluents was an early cause of declining populations. But now other factors that are responsible for poor water quality have emerged, such as agricultural chemicals including chemical fertilizer and pesticides, that find their way from farms in the catchment areas to the rivers, effluents from fish farms and chemical sheep dip. These factors not only affect mussel populations but also host fish populations.

2) Habitat modification or destruction

Habitat destruction mainly includes river engineering; the construction of dams for irrigation, hydroelectric schemes, and flood protection. The impounding of the rivers prevent the movement of migratory host fish upstream, and disrupts the life cycle of the mussels. Habitat modification measures include drainage schemes, flow regulation and fisheries management.

3) Decline in host fish population

The presence of host fish is crucial for the completion of the life cycle of freshwater mussels. The decline in the populations of host fish such as brown trout, sea trout and the migratory salmonids caused by dam construction, or by the increase of chemical pollutants in the water, has a direct impact on the mussel populations, as the larvae that are not able to find a host fish soon perish off. This has an effect on the recruitment of young mussels to the population.

4) Sedimentation or siltation

Poor land management in the catchment areas, such a overgrazing and poor agricultural practices lead to soil erosion, which is eventually washed into the rivers and streams and result in siltation or sedimentation of rivers, altering the habitat of the freshwater mussels.

5) Eutrophication

Nutrient enrichment of waters by agricultural fertilizers, mainly phosphorus-containing chemicals, erosion of soil containing nutrients, release of sewage effluents, urban storm water runoff etc. can lead to excessive plant growth, mainly phytoplankton known as an “algal bloom” in bodies of water such as lakes, estuaries, and slow moving rivers and streams; a phenomenon known as eutrophication. Eutrophication leads to a decrease in dissolved oxygen in the water, caused by the decomposition of dead plant material, that can be catastrophic to both the mussels and the host fish. However, in fast moving rivers the threat posed by eutrophication is minimal. Eutrophication has already eliminated mussel populations in southern and eastern Scotland.

6) Acidification

Acidification of waters can have a detrimental effect on mussel populations. Acidification can be caused by chemical effluents, and decomposition of plant material. The planting of Coniferous trees in the catchment area, leads to acidification of the soil by microbial decomposition, and these acids can can eventually be drained into the rivers.

7) Amateur pearl fishing

Amateur pearl fishing aided by improved accessibility to the upper reaches of rivers have resulted in the wanton destruction of mussel populations, just to try their luck in finding the elusive pearl. The freshwater mussel species Margaritifera margaritifera is not edible. Thus their destruction just for the sake of an occasional pearl is morally unacceptable. The use of tongs to open the mussels and returning them to the water after searching for pearls, unharmed, is highly commendable, but not practiced by pearl hunters.

8) Climate change

Recent climatic changes, with changes in rainfall patterns, resulting in heavier rains, has washed away many of the sand beds in the rivers, the potential areas where young mussels mature. This could have serious implications for the recruitment of young mussels to the populations of freshwater mussels.

Scotland bans the fishing of freshwater mussels in 1998

Dr. Mark Young, an Aberdeen University biologist and freshwater mussel expert is of the opinion that only about a dozen Scottish rivers were now home to the shellfish, compared with nearly a 160 a century ago. Based on the studies of research scientists both in Scotland and the European Union, that painted a bleak picture of the status of the freshwater mussels in Scotland, which according to one report was threatened with total extinction in a period of 25 years, the Scottish Executive declared in 1998, that the freshwater mussel was a protected species under schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981. The law promulgated under the act states that :- “It is an offence to kill, injure, take, intentionally disturb, or damage their habitat, or sell, offer or expose for sale, advertise for sale and transport for sale any freshwater pearl mussel or its pearls without a license from the Scottish Executive. A license issued by the Scottish Executive only permits the sale of pearls obtained prior to 1998. Illegal sales of freshwater pearls carry a penalty of up to six months imprisonment and a maximum fine of £5,000. The enforcement of the law was vested with the Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) and the police. Since the introduction of the law the SNH has been working with the jewelers to raise awareness among the people, and with the police to track down those breaking the law.

Dr Mark Young- research scientist from Aberdeen University involved in the conservation of the freshwater mussel in Scotland.

National Species Action Plan introduced by the Scottish Natural Heritage to restore mussel populations

Having introduced legislation to eliminate one of the main threats to surviving mussel populations, viz. pearl fishing, the Scottish Natural Heritage together with institutions such as the University of Aberdeen, the UK Biodiversity Steering Group and the European Union have drawn up a National Species Action Plan, to encourage measures to save the freshwater pearl mussels from total extinction. The objectives and targets of this action plan are :- 1) Maintaining the size of all viable populations 2) Increasing the size of all viable populations 3) Encouraging the re-colonization of the species in at least 10 suitable former areas by 2005.

The plan also envisages remedial steps to eliminate the causes identified above, that led to the decline in mussel populations.

The present owners of the Abernethy Pearl

After the discovery of the Abernethy Pearl (Little Willie Pearl) in 1967 in the River Tay, by William Abernethy, the professional pearl diver, the pearl was sold for an undisclosed sum to the owners of Cairncross Jewelers in Perth. Cairncross Jewelers placed the Abernethy Pearl on permanent display in their stores, and since then have been viewed by innumerable visitors from the UK and abroad. The pearl was still on display at Cairncross Jewelers in 2006, according to the BBC program “This Week” titled “The Cairngorms” aired on Saturday, August 19, 2006, and also according visitors reports published on the web in 2007. Thus the reports carried by most websites that the Abernethy Pearl was sold in 1992, after almost 30 years of display at Cairncross jewelers appear to be baseless. Cairncross Jewelers is one of only two jewelers that have been granted a license by the SNH to sell pearls and pearl-studded jewelry sourced before 1998, the year the new laws controlling pearling in Scotland became effective.

You are welcome to discuss this post/related topics with Dr Shihaan and other experts from around the world in our FORUMS (forums.internetstones.com)

Related :-

2) Paterson Pearl or Queen Pearl

External Links :-

1) Ecology of the Freshwater Pearl Mussel – Ann Skinner, Mark Young and Lee Hastie.

References :-

1) Pearl Luster – www.pearl-guide,com

2) Pearl Value Factors – Judging and Evaluating Pearls – Amy Hourigan, www.bellaonline.com

3) River Tay – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

4) The Book of the Pearl – George Fredrick Kunz

5) Eutrophication – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

6) Ecology of the Freshwater Pearl Mussel. Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers Ecology Series No.2 English Nature, Peterborough. – Ann Skinner, Mark Young and Lee Hastie.

7) Freshwater pearls mussel their way back into gem shop – by Angie Brown, article published in “The Scotsman” of June 23, 2004.

8) Action Plan for Margaritifera margaritifera – Biodiversity – The UK Steering Group Report – Volume II, Action Plans (December 1995, Tranche I, Vol 2, p 162)

9) Freshwater Pearl Mussel – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

10) The Cairngorms – This Week, Saturday August 19, 2006. www.bbc.co.uk