The Use and Appreciation of Pearls by the monarchs of the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, from the early 16th-century until the end of the monarchy in 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution

In the previous webpage the use and appreciation of pearls by the monarchies of Portugal from the late 14th-century until the early 20th-century was considered in detail. The monarchies considered belonged to the different dynasties that ruled Portugal, such as the House of Aviz (1385-1580); House of Habsburg (1580-1640); the House of Braganza (1640-1834); and the House of Braganza-Saxe-Coburg & Gotha (1834-1910). In the present webpage, the “History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls – Page 10,” the use and appreciation of pearls by the monarchs of the Tsardom of Russia, known as the Tsars and the Tsarinas and later the Emperors and Empresses of the Russian Empire, are considered in detail from the early 16th-century until the abolishment of the monarchy in 1917, following the Bolshevik revolution. The same approach used in the previous webpages making use of colored portraits of the monarchs and their spouses, drawn by renowned artists of the period, is adopted in this webpage too, and gives a wealth of information on the types and designs of jewelry that were popular during their periods of rule. Jewelry incorporating natural pearls appear to be one of the most popular items of jewelry worn by the spouses of the monarchs of Russia, just as the spouses of monarchs of other kingdoms in Europe during this period, such as those of Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Bavaria etc.

The origins of the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire

The vast territory known as Russia today, was during the medieval period and before, several independent nations or kingdoms ruled by sovereigns or monarchs who were known as “Kniaz” (The Prince) or “Velikiy Kniaz” (The Great Prince), sometimes translated as “Dukes” and “Grand Dukes.” Some of these independent kingdoms ruled by Grand Princes were Kiev (838-1240 A.D.); Novgorod (859-1478 A.D.); Vladimir-Suzdal (1168-1389); Tver (1246-1485); and Moscow (1283-1547). It was under Ivan IV Vasilyevich, more famously known as “Ivan the terrible,” the Grand Prince of Moscow, that these independent medieval kingdoms were merged into a single kingdom, the “Tsardom of Russia.” Ivan IV who ruled as the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547, was crowned as the first “Tsar of All Russia” on January 26, 1547, a title which he held until his death on March 28, 1584. Ivan IV also conquered Siberia and the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan during his period of rule, transforming Russia into a multiethnic and multicultural state, the largest in the world, spanning an area of 4.1 million square kilometers, equivalent to 1.5 million square miles.

The “Tsardom of Russia” was ruled from 1547 to 1721 by sovereigns known as the “Tsars” meaning “Caesar” in English, and their queen-consorts were known as “Tsarinas.” From 1721 to 1917, the Tsardom of Russia” became the “Russian Empire” and the Tsars assumed the title of “Emperor of Russia,”ruling their domain with absolute authority. The period of rule of the Tsars of Russia begin with Ivan IV the Terrible and end with the first part of the rule of Peter I the Great, from 1682 to 1721. It was Peter I the Great, who carried out a policy of modernization and expansion, transforming the Tsardom of Russia into an Empire and a major European power. Peter I the Great was proclaimed the Emperor of All Russia, on October 22, 1721. Thus, the period of rule of the Emperors of Russia, begin with Emperor Peter I the Great in 1721 and end with Emperor Nicholas II in 1917.

The Use and Appreciation of Pearls by the Tsars and Tsarinas of the Tsardom of Russia from 1547 to 1721

The Tsardom of Russia that was founded by Ivan IV in 1547 and lasted until 1721 was ruled by a series of kings known as Tsars, belonging to two main dynasties, the Rurik and Romanov dynasties. The Rurik dynasty was the oldest dynasty that previously ruled the Principality of Moscow from 1283 to 1547 and continued its rule after the creation of the Tsardom of Russia in 1547 until the year 1613. However, the latter part of its rule from 1598 to 1613, was a period of instability during which several usurpers, claiming to be from the Rurik Dynasty ruled for short periods of time, leading to the recognition of the Polish Prince, Vladyslaw IV Vasa, as the Tsar of Russia on September 6, 1610, until he was deposed on November 4, 1612, by a Council of Russian Princes who ruled until July 26, 1613, when the first Tsar of the House of Romanov, Michael I ascended the throne.

Appreciation of pearls by the Tsars and Tsarinas of the Rurik dynasty from 1547 to 1612

Ivan IV Vasilyevich, the founder of the Tsardom of Russia, was the first Tsar of the Rurik dynasty, who was proclaimed the Tsar of All Russia on January 26, 1547, after he attained his majority at the age of 16. He ruled Russia for 51 years, first as the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and later as the Tsar of All Russia from 1547, until his death in 1584. Ivan became the Grand Prince of Moscow at the age of 3 years, when his father Vasiliy III died on December 13, 1533. His mother Elena acted as his regent until her death five years later, in 1538. The regency was then taken care of by the highest Russian nobles, the Boyars, until Ivan IV attained his majority in 1547.

Ivan IV Vasilyevich turned out to become the greatest tsar of all Russia, who not only transformed his country from a medieval nation state to a mighty empire, but also introduced political and administrative changes, that had a great bearing on the future course of history in Russia, and survived until modern times, even extending into the post-revolution Communist Russia. The unique concept of “Oprichnina” in which a section of Russia in the northeast was directly ruled by Ivan and policed by his personal guard the “Oprichniki” became a powerful instrument of authoriatianism, that was faithfully adopted by subsequent monarchs of Russia, like Peter the Great and Communist dictators such as Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. Russian expansionism also began during Ivan IV’s rule, that saw the annexation of the Kazan Khanate in 1552, the Astrakhan Khanate in 1556 and Siberia in the 1570s. Ivan IV also succeeded in transforming the new title of “Tsar” into an absolute monarchy; a supreme ruler whose will was not to be challenged by anyone, and associating divinity with the title; the Tsar becoming a divine leader appointed by God to enact his will, which almost approaches powers equivalent to those held by the former Byzantine Caesars.

In the latter part of his rule he launched a seaward expansion to the west, that was not so successful and led to confrontation with Poland, Sweden, Lithuania and Levonian Teutonic Knights, a confrontation that dragged on for over 20 years, with terrible consequences for the Russian economy, further compounded by drought, famine and the deadly plague epidemic. Ivan himself became mentally unstable during the latter part of his life, that resulted in the Oprichniki getting out of control and becoming an instrument of oppression, resulting in the massacre of thousands of his own subjects in Novgorod in 1570, and the accidental killing of his own son in 1581 by striking him on the head with a pointed staff.

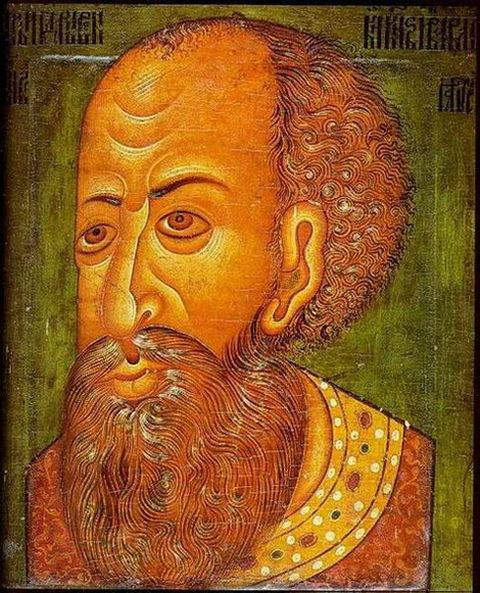

Portrait of Ivan IV in the National Museum of Denmark

The above portrait of Ivan IV in the National Museum of Denmark was drawn by an unknown artist probably around the year 1600, after the death of the great Tsar in 1584. The artist has depicted colored gemstones embroidered on the collar of the Tsar’s robe, a practice common among the monarchs of this period, the white stones probably representing pearls, popular in ornamentation during this period.

Ivan Grozny frame from the Great State Book of 1672

Ivan Grozny frame shown above is from the Great State Book of 1672, that contains portraits, coat-of-arms and official seals of the Tsars of Russia. The portrait drawn by the unknown artist depicts apart from colored stones embroidered on the upper part of the ceremonial robe, four rows of pearls, two around the neck and two around its lower end.

Ivan IV demonstrates his treasurers to the ambassador of Queen Elizabeth I of England, Jerome Horsey

The above oil on canvas painting by Alexander Litovchenko in 1875, depicts Tsar Ivan IV of All Russia, demonstrating his treasurers to the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth I of England, Jerome Horsey. Standing behind Tsar Ivan IV is his son and heir Feodor. Among the many treasurers depicted by the artist in the painting are several items incorporating pearls, as seen on the bottom right of the painting.

Ivan IV admiring his sixth wife Vasilisa Melentyeva

The above painting by Grigory Sedov in 1875 depicts Ivan IV admiring his sixth wife Vasilisa Melenteyva, the widow of a prince who died in the Livonian war. The Tsarina is shown wearing a headdress studded with pearls and other colored gemstones, and a dress embroidered with vertical rows of pearls in front. The Tsar himself is depicted by the painter, wearing a head ornament incorporating pearls, and a black robe studded with rows of white pearls, around the neck, and on either side of the yellow border of the robe. What looks like a rope of pearl beads has been placed on the top of a table on the right hand side of the painting.

1897-Portrait of Ivan IV by Viktor Vasnetsov

The above oil-on-canvas painting by Viktor Vasnetsov in 1897, depicts Tsar Ivan IV in a standing posture holding his septre. The Tsar is shown wearing a long printed robe, and carrying what looks like a rosary in his hand, made of beaded pearls.

Anastasia Romanovna Zakharyina-Yurieva – First wife (1547-1560) of Ivan IV, and First Tsarina of All Russia

Soon after Ivan IV was proclaimed the Tsar of All Russia, on January 26, 1547, earnest efforts were made to find a suitable spouse for the young Tsar. All Russian nobles were invited to present their eligible daughters at the Kremlin for a selection process, and out of over a thousand prospective brides, the lucky one to be chosen was Anastasia, the daughter of Boyar Romanov Yurievich Zakharyin-Yuriev and his wife Uliana Ivanovna. The marriage took place on February 3, 1547. Ivan IV was 16 and Anastsia 17 at the time of their marriage. The marriage turned out to be a happy one producing six childeren. Anastasia’s marriage to Ivan IV lasted 13 years, until 1560, during which period she appeared to exert a moderating influence on her husband’s volatile character. Anastasia died in August 1560 after a lingering sickness possibly caused by poisoning. Ivan IV was devastated by her death, and suspecting that the Boyars had poisoned her, got several of them tortured and executed.

Statute of Anastasia Romnovna in Veliky, Novgorod

Maria Temrjukovna – Second wife (1561-1569) of Ivan IV, and second Tsaritsa consort of All Russia

Around an year after Anastasia Romanovna’s death, the beautiful Kucenej, the daughter of the Muslim prince Temrjuk of Kabardia, was presented to Ivan IV in Moscow. Ivan was so strongly attracted by Kucenej’s beauty, that he decided to marry her immediately. Their marriage took place on August 21, 1561, soon after Kucenej was baptised and came to be known as Maria Temrjukovna. Maria was 17 and Ivan IV 31 at the time of their marriage. Though the marriage turned out to be successful, Maria was never fully integrated to the Muscovite way of life, and was generally disliked by her subjects, possibly because of her non-Christian origin and her alleged vindictiveness and manipulation of her husband. Maria gave birth to a son in 1563, who was named Vasiliy, after Ivan IV’s father Vasiliy III, but the infant died just two months after its birth. Maria died at the age of 25, in 1569, also of suspected poisoning like her predecessor Anastasia and several suspects had to face the wrath of Ivan IV for their misdeed.

Marfa Vasilevna Sobakina – Third Wife (October 28, 1571 to November 13, 1571) of Ivan IV and third Tsarina of All Russia.

Two years after the death of Maria, Ivan IV decided to take his third wife. From among 12 marriage finalists Ivan himself selected the beautiful Marfa, the daughter of a Novgorod based merchant Vasiliy Sobakin. However, soon after her selection, Marfa was affected by a mysterious illness that resulted in rapid loss of weight and weakness, that barely enbled her to stand. Yet her marriage to Ivan IV went ahead, and took place on October 28, 1571. Unfortunately, Marfa died just two weeks after her marriage, on November 13, 1571, totally devastating Ivan IV, because of the repeated misfortunes that led to the premature death of his wives. The incidence further increased the mistrust and suspicion of Ivan IV towards some of his loyal subjects, and suspecting poisoning for the third time, got several of them executed, including Mikail Temjruk, the brother of his previous wife Maria Temrjukovna. However, the actual cause of Marfa’s death was believed to be accidental poisoning by her own mother, who had given her a medicinal preparation to increase her fertility.

Forensic facial reconstruction of Marfa Sobakina by Sergei Nikitin

Anna Alexeievna Koltovskaya – Fourth wife (1572-1574) of Tsar Ivan IV and fourth Tsarina of All Russia

After the death of Marfa Sobakina, Ivan IV sought a fourth wife, but had to face difficulties in securing one, as the Russian Orthodox Church prohibited fourth marriages. Ivan claimed that his 4th-marriage was still legal as he was not able to consummate his 3rd-marriage. Hence without seeking the blessings of the Church, he married his 4th-wife, Anna Alexeievna Koltovskaya, the daughter of a courtesan Alexei Koltovski, on April 29, 1572. Subsequently the Church agreed to his marriage with certain conditions, after Ivan made a heartfelt appeal to the priests at a meeting held in the Church of Assumption. However, the marriage did not produce any issue, and after two years Ivan repudiated his wife and sent her to a convent, where she assumed the monastery name of Daria, and lived until her death in 1626.

Anna Vasilchikova – Fifth wife (1575-1576/77) of Tsar Ivan IV an fifth Tsarina of All Russia

In January 1575, Ivan IV took his fifth wife, Anna Vasilchikov. Being contrary to the laws of the Orthodox Church, Ivan did not care to seek the blessings of the Ecclesiastical Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, which even frowned on his 4th-marriage three years ago. However, like the previous marriages this marriage too did not last long, and Anna Vasilchikov is believed to have died under mysterious and violent circumstances, either in 1576 or 1577.

Vasilisa Melentyeva – Sixth wife (1579) of Tsar Ivan IV and sixth Tsarina of All Russia

Ivan IV continued to repudiate the authority of the Russian Orthodox Church, and decided to take a sixth wife in 1579. However, unlike his previous marriages, this marriage was different as his 6th-wife was a widow of a prince who served in the Livonian War. Ivan was attracted by her beauty and sweet nature, but a few months after the marriage, he discovered to his horror, that she was having an affair with a prince named Devletev. The fate of the lovers were sealed given the despotic nature of the much-feared king. He forced Vasilisa to watch her lover being impaled, and then buried her alive in a cloister.

1886-portrait of Vasilisa Melentyeva by Nikolai Vasilyevich Nevrev

Ornaments worn –

In the above portrait of Vasilisa Melentyeva drawn by the artist 300 years after her death, the Tsarina is depicted wearing the following ornaments :-

Multistrand pearl necklace.

Pearl drop earrings.

Row of pearls on the headdress.

Row of pearls equally spaced along the front midline of the dress appearing like a row of buttons, and probably used as such.

Another such row on the purple velvet-like robe over the yellow silk-like robe.

Maria Dolgorukaya – Seventh wife (1580) of Tsar Ivan IV and seventh Tsarina of All Russia

Ivan IV took his 7th-wife in 1580 totally ignoring the sensitivities of the Russian Orthodox Church. His new wife was Maria Dolgorukaya, a descendant of Prince Yuri I Dolgoruki, Prince of Kiev, Rostov and Suzdal, from whom Ivan IV also descended through his son, Vsevolod III Yuryevich. The marriage did not produce any issue, and fatefully she too was discovered to have a lover, and was ordered by Ivan to be killed by drowning.

Maria Feodorovna Nagaya – Eigth wife (1581-1584) of Tsar Ivan IV and eigth Tsarina of All Russia

Ivan IV took his eighth and last wife, Maria Nagaya, in 1581, and in 1582 she gave birth to his son Dmitry. Maria Feodorovna Nagaya was the only wife of Ivan IV, who outlived the mighty Tsar. When Ivan IV died on March 28, 1584, he was succeeded by his only surviving son, Feodor I Ivanovich, by his first wife, Anastasia Romanovna. Feodor was a simple and pious tsar, spending most of his time in prayers and taking little interest in politics. He left the task of governing the country to his able brother-in-law, Boris Godunov, who sent Maria Nagaya, her son Tsarevich Dmitry and her brothers into exile in Uglich. Maria Nagaya lived in Uglich until 1591, when her son Tsarevich Dmitry died suddenly under mysterious circumstances. Maria and her brothers were accused of “criminal negligence” that led to the incarceration of Maria’s brothers, and Maria herself was forced to become a nun and enter a monastery. Tsaraveich Dmitry was the next in line of succession to the throne after Feodor I who died without surviving issue. Thus, the death of Tsarevich Dmitry under mysterious circumstances precipitated a succession crisis, that led to the “Time of Troubles” in Russian history, not only bringing an end to the centuries-old line of Tsars of the Rurik dynasty, but also the appearance of several false Dmitrys who staked a claim to the Russian throne. Maria Najaya was forced to recognize False Dmitry I as her own son in 1605, that led to freedom for her family and the restoration of their property and ranks. However, after False Dmitry I’s death in 1606, she renounced him as his son.

Irina Feodorovna Godunova – Wife of Tsar Feodor I Ivanovich and Tsarina consort of All Russia

After Tsar Ivan IV died on March 28, 1584, he was succeeded by Feodor I Ivanovich, his only surviving son by his first wife, Anastasia Romanovna, and crowned Tsar of All Russia, at the Church of Assumption in Moscow, on May 31, 1584. Pious and religious-minded Feodor, left the task of governing to his able brother-in-law Boris Godunov. As head of the Regency Council, Boris Godunov’s achievements included, defeating a Tartar raid on Moscow in 1590; recovering towns lost to Sweden previously, in 1595; building towns and fortresses along the northeasern and southeastern borders of Russia, to keep the Tartar and Finnic tribes in check; colonizing Siberia with new settlements; freeing the Russian Orthodox Church from the influence of the Patriarch of Constantinople and encouraging trade with other nations, particularly merchants from England who were given trade concessions. His most controversial domestic reform introduced in 1597, prohibiting the peasantry from going from one landowner to another, though intended to secure revenue, eventually led to the most oppressive form of serfdom. Boris Godunov’s regency continued until the death of Feodor I Ivanovich on January 7, 1598.

Feodor the Bellringer – the last Rurikid Tsar of Russia (from the book “Story of Russia” by R. Van Bergen)

Aleksey Kivshenko painting (1851-96) titled Feodor Ivanovich presents a golden chain to Boris Godunov. Tsarina Irina Feodorovna Godunova is also depicted in the painting watching the proceedings.

Feodor I married Irina Feodorovna Godunova, sister of Boris Godunov, in 1580. Both Feodor and Irina were 23 years of age at the time of their marriage. She became the Tsarina of All Russia upon the ascendancy of her husband as the Tsar in 1584. Irina was under pressure to produce a male heir, as the future of the Rurik dynasty that ruled Russia since the 9th-century was in doubt if Feodor I died without a son. It was doubtful whether Ivan IV’s son Dimitry, by his 8th-wife Maria Nagaya, would be considered as a legitimate successor to the Russian throne, as the Russian Orthodox Church recognized only up to four marriages as legitimate. However, Dimitry too died under mysterious circumstances in May 1591, and the pressure on Irina to produce an heir further increased. Eventually after 12 years of marriage, Irina gave birth to a daughter, Feodosia in 1592, but the girl did not live long and died in 1594. Failure of Feodor and Irina to produce anymore children brought to an end the central branch of the Rurik dynasty, paving the way for the period of instability in Russian history known as the time of troubles. When Feodor I died on January 7, 1598, Irina as the reigning Tsarina could have technically taken the throne, as the male line of the Rurik dynasty had become extinct with the death of her husband. However, there had been no precedent of a woman ever ruling in Russia before, hence she retired to the Novodevichy monastery in Moscow, taking the monastic vows under the name of Aleksandra. Irina outlived her husband by five years dying in October 1603 in the same monastery.

Forensic facial reconstruction of Irina Feodorovna Godunova depicting her as a nun after she entered the Novodevichy Monastery

Maria Grigorievna Skuratova-Belskaya – Wife of Tsar Boris Godunov (1598-1605) and Tsarina consort of All Russia

The death of heirless Feodor I on January 7, 1598 created a power vacuum, and to fill this gap Patriarch Job of Moscow proposed that Boris Godunov,the head of the Regency Council that guided Feodor I, be elected as the new Tsar of Russia. This was followed by the National Assembly that unanimously elected him as Tsar on February 21, 1598. Boris Godunov accepted the throne of Russia from the National Assembly and was formally crowned as Tsar on September 1, 1598.

Boris Godunov, though not of royal lineage, turned out to become one of the greatest tsars of Russia, who realizing the need to catch-up with intellectual progress in the west, introduced educational and social reforms, importing foreign teachers on a large scale and sending young Russians abroad to be educated. However, his suspicion of the aristocratic boyars led to their persecution on unsubstantiated charges, and cast a shadow over his rule, that subsequently led to his wife and his son and successor, Feodor II, paying the price for his excesses.

Boris Godunov after he was crowned Tsar of Russia on 1st September, 1598

The above portrait of Boris Godunov depict him with the coronation regalia of the Tsardom of Russia, that include the coronation robes, the Monomakh’s crown, the scepter, orb, and a gold chain with a cross as pendant. The regalia appear to be heavily studded with pearls and colored stones as seen in the painting.

In the coronation robes, the flap going round the shoulders, the midline of the robes and the edges of the sleeves, are studded with colored stones and lined with row of pearls.

The Monomach’s crown used in the coronation of Russian Tsars, is also heavily studded with pearls and colored stones, and surmounted by a cross.

The Orb held by the Tsar in his left hand is also studded with colored stones and lined by rows of pearls, and surmounted by a cross.

In the period 1570/1571, Boris Godunov married Maria Grigorievna Skuratova-Belskaya, the daughter of the head of Ivan’s personal guard and secret police (Oprichnik), Malyuta Skuratova-Belskiy. The marriage strengthened Godunov’s position in Ivan IV’s court, that was further enhanced in 1580, when Ivan IV chose Godunov’s sister, Irina to be the wife of his second son Feodor Ivanovich, who eventually succeeded Ivan IV. Boris Godunov’s eldest child, a daughter named Xenia, was born in 1582. His first son, Ivan, was born in 1587, but died in infancy in 1588. His second son, Feodor, was born in 1589 and eventually succeeded his father, after his death on April 23, 1605. The 16-year old Feodor II reigned for just over a month, and was strangled to death together with his mother, by the agents of False Dmitriy I in his apartment on June 11, 1605.

Konstantin Makovsky’s 1862-painting of the murder of Feodor Godunov and his mother Maria Grigorievna Skuratova-Belskaya by the agents of False Dmitry

Konstantin Makovsky’s painting above shows Fedor II’s mother, Maria Grigorievna grieving over the body of her dead son, while one of the assassins attempts to pull her away from her dead son, before meting out the same punishment to the dowager queen. In the painting the artist has depicted the queen wearing a headdress incorporating strings of pearls as festoons, and also a multistrand pearl necklace.

Marina Mniszech – Wife of False Dmitriy I and Tsarina of All Russia from 1605 to 1606 during the time of troubles

Towards the end of Boris Godunov’s rule, around 1600, there appeared in Moscow a learned young man with aristocratic skills, like riding and literacy, and with the ability to speak both the Russian and Polish languages. The young man impressed Patriarch Job of Moscow, and claimed to be Dmitriy, the youngest son of Ivan IV by his last wife Maria Nagaya, who had escaped assassination attempts by the agents of Boris Godunov, after his mother had given him to the care of a doctor, who had hidden him in various monastaries. After the death of the doctor, he claimed that he escaped to Poland, where he worked briefly as a teacher. A number of people who had known Tsar Ivan IV also claimed that Dmitriy did resemble his father. When Boris Godunov ordered the arrest of the young man, he escaped to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where he sought the assistance of the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa and other nobleman to claim the throne of Russia. Dmitriy also converted publicly to Roman Catholicism in 1604, to obtain the support of the Jesuits and the Papal Nuncio, and probably gave an undertking to his Polish supporters to deliver Orthodox Russia to Roman Catholicism. Boris Godunov, who heard about the pretender Dmitriy, claimed that the man was a runaway monk, born as Yuri Otrepyev and given the name Grigory Otrepyev at the monastery. During this period Boris Godunov’s popularity was on the wane, and most of the boyars whom he persecuted appeared to be in favour of False Dmitriy’s claim.

False Dmitriy then successfully organized a small army of around 3,500 soldiers, and entered Russia in June 1604. Marching towards Moscow, the enemies of Boris, including the southern Cossacks joined his army. The advancing army fought two battles with the Russian forces, winning the first and capturing several important towns, and badly losing the second engagement and nearly being annihilated, when the news of the death of Tsar Boris on April 23, 1605, reached the battle field. Most of the Russian troops then defected to Dmitriy’s side, and on June 20, 1605, Dmitriy made his triumphal entry into Moscow.

Soon after the death of Boris Godunov on April 23, 1605, his 16-year old son, Feodor II was proclaimed as tsar. However, on June 11, 1605, the envoys of False Dmitriy arrived in Moscow, and read a proclamation publicly in the Red Square, announcing the removal of the tsar. Soon after this a group of boyars who supported false Dmitriy, seized control of the Kremlin and arrested Feodor II and his mother, Maria. Then on June 20, as False Dmitriy entered Moscow triumphantly, both Feodor II and his mother were strangled to death by Dmitriy’s agents.

Portrait of False Dmitriy I by unknown artistDmitriy was crowned as tsar on July 21, 1605. Soon after this he visited the sepulchre of his purported father, Ivan IV, and the convent of his purported mother, Maria Nagaya, who accepted him as his son. In return Dmitriy gave freedom to the family members of Maria Nagaya, and restored their property and ranks. He exacted revenge from the Godunov family, executing everyone of them, except the daughter of Boris Godunov, Xenia, whom he kept as his concubine. Most of the families of boyars exiled by Godunov, such as the Shuiskys, Golitsins and Romanovs were allowed to return to Moscow and their property and ranks restored to them. Patriarch Job of Moscow was exiled, as he did not recognize the new tsar.

Dmitriy restored Yuri’s Day that was abolished by Boris, once again allowing serfs to move from one landowner to another. He also sought alliances with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Roman Pope, who assisted him in claiming the Russian throne. However, it was this same policy of appeasing the Roman Catholic Church that led to his undoing barely an year after his ascendancy to the throne.

Portrait of False Dmitriy I in coronation robes by artist Szymon Boguszowicz executed around 1606

After Dmitry captured Moscow in June 1605, he sent a diplomatic mission to Poland in November of that year, seeking the hand of Marina Mniszech, the daughter of a Polish nobleman Jerzy Mniszech, in mariage. Dmitry had met Marina previously in 1604, at the court of one of the Polish-Lithuanian Magnates, and agreed to marry him. A Catholic wedding ceremony was performed by the bishop of Krakow in November 1605, at Krakow in Poland, attended by the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa himself, and Dmitriy was represented by the envoy from Moscow. Six months later, on May 8, 1605, Maria Mniszech and her father, with a retinue of aound 4,000 entered Moscow in a triumphant parade, and at a ceremony that followed Patriarch Ignatius confirmed their marriage, and crowned Maria as Tsarina by placing the Rurikid crown on her head. Maria Mniszech did not convert to Orthodox Christianity before the confirmation of their marriage, as required by age-old tradition, when a woman of a different faith married a Russian Tsar.

This act of False Dmitry, aroused the resentment and anger of the Russian Orthodox Church, the boyars and the general population, and led to the formation of anti-Dmitriy movement, opposed to his policy of close co-operation with Poland, headed by the boyar Prince Vasily Shuisky. Popular support for the movement increased, as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth forces, still stationed in Moscow and guarding Dmitriy, were involved in various criminal activities. Finally on May 17, 1606, just two weeks after the controversial marriage ceremony, anti-Dmitriy conspirators stormed the Kremlin. Dmitriy made an attempt to escape through a window, and in the process had a fall and broke his leg, and was shot dead. Thousands were killed including many members of the Polish entourage that accompanied Marina Mniszech to Moscow. Marina Mniszech and her father were taken prisoner. Marina’s life was spared and sent back to Poland the following year, but her father was exiled to Yaroslavl. Prince Vasily Shuisky, the leader of the popular movement against False Dmitriy then ascended the throne as the new Tsar of Russia.

Portrait of Tsarina Marina Mniszech in coronation robes executed by Szymon Boguszowicz in oil on canvas around 1606, currently in the State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Ornaments worn by Marina Mniszech

Two strands of pearls as head band.

Single large spherical pearls topping the upturned lobes of her headdress.

Pearl drop earrings.

Single-strand pearl necklace.

Single-strand of large pearls decorating the bodice of her dress like a festoon.

A stomacher incorporating a ring of eight large drop-shaped pearls.

Crown incorporating rows of large spherical pearls.

A second portrait of Tsarina Marina Mniszech in coronation robes by Szymon Boguszowicz currently in the Wawel Royal Castle, Krakow, Poland

Ornaments worn by the tsarina-

Two strands of pearls as headband.

Pearl drop earrings.

Single-strand pearl necklace.

Single strand of pearls forming a festoon-like decoration on the bodice of the dress.

Stomacher made up of a ring of pearls.

Crown studded with pearls.

Tsar Vasiliy IV – Tsar of Russia from 1606 to 1610

As head of the popular revolt that ousted and killed False Dmitriy I, Prince Vasiliy Shuisky ascended the throne as the new tsar of Russia, on May 19, 1606. Prince Vasiliy was a skilled manipulator and was able to gain the confidence of not only tsar Feodor I but also his successor Boris Godunov. Thus, during this period he became one of the leading boyars of the Tsardom of Russia. It was to Prince Vasiliy Shuisky that Tsar Boris Godunov entrusted the important task of inquiring into the circumstances of the death of Tsarevich Dmitriy Ivanovich, the youngest son of Ivan IV, at Uglich in 1591, where he lived with his mother, Maria Nagaya. Shuisky’s finding was that Tsaraveich Dmitriy commited suicide by cutting his throat during an epileptic seizure. However, soon after the death of Boris Godunov and the accession of his son Feodor II, when it became clear that False Dmitry I would take over the throne, Shuisky went back on his own findings to gain the favour of the pretender, and in fact went to the extent of recognizing the pretender as the “real’ Dmitriy, even though his finding previouly was that the boy had committed suicide. The shrewd Shuisky toed the line of False Dmitriy as long as he was popular, but when False Dmitriy committed the blunder of choosing a Polish princess as his wife and married her without converting her to Orthodox Christianity, and thus earned the wrath of the Russian Orthodox Church, the boyars and the general population, Shuisky quickly seized the opportunity, and gave leadership to the anti-False Dmitriy faction. This timely move on his part put him on the throne of Russia soon after False Dmitriy was killed on May 17, 1606, and Shuisky once again declared that the real Dmitriy had indeed been killed, and False Dmitriy was an impostor.

Prince Vasiliy Shuisky ascended the throne of Russia as Tsar Vasiliy IV, and reigned for just over four years, from May 19, 1606 to July 19, 1610. Tsar Vasiliy IV was a weak ruler, and his authority was not recognized all over Russia. Even in Moscow itself he had little or no authority. It was surprising that he was able to continue for four years. This was probably because the boyars had no suitable candidate to takeover the mantle of leadership, or they could not agree on a single person, as all of them were ambitious. However, towards the latter half of his rule, Vasiliy IV got the backing of his cousin, Prince Mikhail Skopin-Shuisky, who together with Jacob de la Gardie commanded a Russio-Swedish army that defended Moscow against the armies of False Dmitriy II and the Polish King Sigismund III Vasa. Eventually the Russio-Swedish army was routed by the Polish forces, under Stanislaw Zolkiewski, at the battle of Klushino on July 4, 1610. Vasili Shuisky was then overthrown by the Council of Seven Boyars on July 27, 1610, who elected the 15-year-old Wladyslaw IV Vasa, son of the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa, as the new Tsar of Russia. The Poles entered Moscow on September 21, 1610, sparking riots in Moscow that were brutally suppressed and the city set on fire. Vasili IV was forced to take on the robes as a monk, and eventually ended up as a prisoner in the Gostynin Castle in Warsaw, where he died in 1612. Vasili IV was the last ruler of the Rurikid dynasty to rule Russia. He did not get married and was 60 years at thetime of his death.

Portrait of Tsar Vasiliy IV of Russia by Viktor Vasnetsov in 1897

The above portrait of Vasily IV of Russia, painted by Viktor Vasnetsov in 1897, depicts the tsar wearing the ceremonial robes, the Monomakh’s crown and the royal scepter in his right hand. Apart from colored stones, the upper part of the ceremonial robe is embroidered with four rows of pearls, two rows around the neck and two rows around its lower edge.

False Dmitriy II, second pretender to the Russian throne, who claimed to be Tsarevich Dmitriy Ivanovich of Russia

During the reign of Tsar Vasili IV around July 1607, there appeared at Starodub, a highly educated young man, with aristocratic skills, who spoke both Russian and Polish languages and an expert in liturgicl matters. The man claimed to be the Muscovite boyar Nagoy, but later confessed under torture to be Tsarevich Dmitry, the youngest son of Ivan the Terrible. The young man was taken at his word and soon became the nucleus of an anti-Russian alliance, that included the Cossacks and Poles, and even ordinary muscovites who were attracted by the promise of wholesale confiscation of the estates of Boyars. As the popularity of False Dmitriy II increased, the ambitious Jerzy Mniszech, the father-in-law of False Dmitriy I, approached the new False Dmitriy and got his consent to marry his daughter Marina Mniszech, the widow of the first False Dmitry. The marriage of False Dmitriy II to the Polish princess, Marina Mniszech, earned the support of the magnates of the Polish Luthunian Commonwealth, who had previously supported False Dmitriy I. They made funds avilable for his campaign and gave him an army of 7,500 soldiers. False Dmitriy II’s army quickly captured many important towns in Russia, that was taken over and reinforced by the Polish-Lithuanian army, and in the spring of 1608 his army advanced towards Moscow, routing the army of Tsar Vasily Shuisky at Bolkhov. False Dmitriy II set up camp at the village of Tushino, just outside Moscow, where an army of over 100,000 men assembled, consisting of Polish, Cossack and other soldiers. He also won the allegiance of more cities, such as Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Vologda and Kashin. However, when the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa arrived at Smolensk, most of his Polish soldiers deserted his army and joined the forces of the king. Around this time, a strong Russio-Swedish army under the joint-command of Prince Mikhail Skopin-Shuisky and Jacob de la Gardie approached Tushino, and false Dmitriy II was forced to flee tushino, disguised as a peasant. He escaped to Kostroma where he was joined by his wife Marina Mniszech who was now pregnant with his child. False Dmitriy II made another unsuccessful attack on Moscow, and with the help of his Cossack forces held on to territory in south-eastern Russia. However, on December 11, 1610, after he had drunk deeply with his boyar friends, he was killed by a young Tartar prince, Peter Ursov, whom he had punished by flogging previously.

Marina Mniszech widowed for the second time gave birth to False Dmitriy’s son, Ivan Dmitriyevich, posthumously in January 1611. Marina Mniszech then married her third spouse Ivan Zarutsky, who took upon himself the task of supporting the nomination of her son, Ivan Dmitriyevich, for the Russian throne. However, by the summer of 1613, after the Poles had been expelled from Moscow and Michael Romanov, the son of Patriarch Filaret had been elected as the new tsar, Marina Mniszech and Ivan Zarutsky, having lost their supporters fled to Astrakhan. The people of Astrakhan, did not like the pretender and his family staying in their city, and when they rose against them in 1614, they escaped into the steppes. Ivan Zarutsky failed to get support for another Cossack uprising, and was finally captured by the Cossacks around June 1614 and handed over to the government. Ivan Zarutsky and Marina Mniszech’s 3-year-old son, Ivan Dmitriyevich were executed in 1614, and Marina Mniszech died in Prison in Moscow soon afterwards.

Sketch of False Dmitriy II by unknown artist around 1610

The above sketch of False Dmitriy II by unknown artist, probably drawn around 1610, depicts him wearing a woolen cap, with a hair ornament affixed to it on the side. The hair ornament appears to be made up of a large oval-shaped pearl, with a smaller drop-shaped pearl hanging from it, and a plume of feathers rising from above.

Nominal rule of Wladyslaw IV Vasa as Tsar of Russia from September 6, 1610 to November 4, 1612

After Tsar Vasili IV was deposed by the Council of Seven Boyars on July 27, 1610, they elected the 15-year-old Wladyslaw IV Vasa, the son of the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa, as the new Tsar of Russia, on September 6, 1610. The Poles entered Moscow on September 21, 1610, suppressing brutally riots that broke out in the capital city, which was set on fire. King Sigismund III Vasa refused to accept the suggestion of the Council of Seven Boyars to send his son Wladyslaw to Moscow to accept the throne after converting to Orthodox Christianity. This was because of the unsettled conditions in Moscow where anti-Polish feelings were running high, and King Sigismund III Vasa’s ultimate aim of converting Moscow’s population from Orthodox Christianity to Catholicism. However, the Council of Seven Boyars continued to recognize, Wladyslaw IV Vasa as the Tsar of Russia, and struck Muscovite silver and gold coins in the mints of Moscow and Novogrod, with his titulary, “Tsar and Grand Prince Vladislav Zigimontovich of all Russia.”

The Polish occupation of Moscow, provoked a national uprising against the invasion in 1611 and 1612. In opposition to the “Council of Seven Boyars” and the Poles, a “Council of All the Land” was formed in April 1611, headed by Prince Dmitriy Mikhailovich Pozharsky. A volunteer army was formed led by Prince Dmitriy Pozharsky and the merchant Kuzma Minin. This army fought with the occupying Polish forces and finally expelled them from the capital on November 4, 1612. The activities of the Council of Seven Boyars and the nominal rule of Wladyslaw IV Vasa ended with the expulsion of Poles from Moscow on November 4, 1612.

Portrait of Prince Wladyslaw IV Vasa by Peter Paul Rubens, executed on oil on canvas in 1624, during his visit to Brussels as the personal guest of Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain

The above portrait of Prince Wladyslaw IV Vasa before he was elected king of Poland, depict him wearing a hat with a hat-ornament affixed to one side. The hat ornament incorporates a large drop-shaped pearl and several smaller spherical pearls. The prince also appears to be wearing another vertical pearl ornament just below the collar of his coat.

Appreciation of pearls by the Tsars and Tsarinas of the Romanov dynasty

The Time of Troubles in Russian History that began with the death of the heirless Feodor I Ivanovich on January 7, 1598, marking the end of the main line of Tsars of the Rurik dynasty, was actually a period of succession struggles, resulting in civil wars and foreign intervention, further compounded by the Russian famine of early 17th-century, caused by extremely cold summers that wrecked crops, and increased social disorganization. This period of instability finally came to an end in February 1613, with the expulsion of Poles from Moscow, and the election of the 16-year-old Michael Romanov, the son of Patriarch Filaret who was living in captivity in Poland, as the new Tsar of Russia, by a National Assembly constituted of representatives from around fifty cities in Russia. This marked the beginning of a new dynasty of Tsars in Russia, known as the Romanov dynasty, that ruled Russia until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

Tsar Michael Fyodorovich Romanov – First Tsar of the House of Romanov from 1613 to 1645

Michael Romanov was crowned Tsar of All Russia on July 22, 1613. The new Tsar with the help of his counsellors immediately set about restoring law and order in the vast country, and one of his first tasks was the elimination of gangs of robbers who devastated the country side. He then made peace with Russia’s former enemies, Sweden and the Polish-Lithunian Commonwealth, with whom he signed peace treaties in 1617 and 1619 respectively. The signing of the peace treaty with Poland, enabled the Tsar’s father, Feodor Nikitich Romanov (Patriach Filaret) to return from captivity in Poland in 1619, and take over the affairs of the government, on behalf of his young son, Tsar Michael Romanov, a position which he held, until his death in 1633. Tsar Michael became famous as a gentle and pious Prince, who gave little trouble to anyone, preferring to rule from behind the scenes, effacing himself behind his counsellors.

Portrait of Tsar Michael I of Russia by unknown artist depicting him with the coronation regalia of the Tsardom of Russia

Coronation regalia depicted on the portrait –

Coronation robes heavily embroidered with rows of pearls.

The Orb set with pearls and colored stones.

Monomakh’s Cap or Crown, set with pearls and colored stones.

The royal scepter.

“Millennium of Russia” monument in Veliky, Novgorod depicting Michael I being offered the Monomakh’s Cap and scepter by Kuzma Minin and protected by Dmitriy Pozharsky

Eudoxia Streshneva – Second wife (1626-1645) of Tsar Michael Fyodorovich Romanov (1613-1645)

Tsar Michael Romanov married twice. His first wife was Maria Vladimirovna Dolgorukova, whom he married in late 1624, but died four months later in 1625. His second wife was Eudoxia Streshneva, whom he chose himself from an array of fair noble maidens, and married on February 5, 1626. The marriage proved to be a very successful one, producing 10 children, out of whom only five survived into adulthood. The second surviving child, Tsarveich Alexis succeeded his father, as the second tsar of Russia of the Romanov dynasty. Eudoxia Streshneva died just five weeks after her husband in 1645.

Potrait of Eudoxia Streshneva second wife of Tsar Michael I

Ornaments worn by the Tsarina –

Robes embroidered with pearls.

Brooch used as a pin holding together ends of the outer robe.

Crown set with rows of pearls and colored stones.

Earrings probably set with pearls.

Tsar Michael I choosing his bride from several fair maidens in 1626

The above painting by Ilya Yefimovich Repin executed between 1884 and 1887, depict Tsar Michael I choosing his bride from an array of fair maindens in 1626. The tsar chose Eudoxia Streshneva as his second bride, whom he married on February 5, 1626. All the maidens assembled appear to be heavily bedecked with ornaments incorporating pearls, such as pearl drop earrings, pearl necklaces, brooches and stomachers, and bracelets. The tsar himself is depicted wearing some form of pearl ornament on the upper part of his robes.

Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich Romanov – Second Tsar of the House of Romanov from 1645 to 1676

When Tsar Michael Romanov died on July 12, 1645, he was succeeded by his eldest and only surviving son, Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov who ascended the throne at the age of 16 as Tsar Alexis I. During the early years of his rule, Tsar Alexis I’s chief advisor and minister was boyar Boris Morozov, who adopted a cautious foreign policy, securing a truce with Poland and avoiding any conflicts with the Ottoman empire. By abolishing many unnecessary and expensive court offices, and limiting privileges given to foreign traders he relieved the public burden. In 1648, Boris Morozov successfully procured the marriage of the 19-year-old tsar to his relative, the 23-year-old Maria Miloslavskya. In fact the Tsar was required to choose his bride from among hundreds of noble girls, but the selection was managed by Boris Morozov, who manipulated the selection to favour his relative, Maria Miloslavskya, whom the Tsar married on January 17, 1648. Ten days later, Boris Morozov himself married a sister of Maria Miloslavskya, a marriage that enhanced his power in the court. However, Boris Mozorov soon became unpopular that led to the Moscow Salt Riots of May 1648, leading to his dismissal and exile to a monastery.

After a period of disturbances all over the Tsardom following the Salt Riots, patriarch Nikon who had displayed tact and courage during the disturbances at Novgorod, was appointed the Tsar’s chief minister in 1651. After peace was restored all over the tsardom, Tsar Alexis diverted his attention towards Russia’s neighbour and longtime enemy, the Polish-Lithunian commonwealth who had annexed Russian lands during the Time of Troubles. He took advantage of Poland’s weakness and disorder following the Khmelnitsky uprising, and having got the approval of the national assembly, ordered the Russian army to attack lands held by the commonwealth. The campaign led to a series of wars involving Russia, Poland and Sweden, that eventually led to the Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667, in which Poland accepted the loss of Left-bank Ukraine, Kiev and Smolensk to Russia. Tsar Alexis was outraged by the killing of King Charles I of England in 1649, by the Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell. In retaliation, he broke off diplomatic relations with England, banned all English merchants from entering Russia, provided financial assistance to the widow of Charles I and accepted all royalist refugees in Moscow.

Portrait of Tsar Alexis I of Russia by unknown west European artist in the 17th-century

Royal regalia depicted on the portrait

The above portrait of Tsar Alexis I of Russia by an unknown west European painter, probably executed in the 17th-century, depict the tsar wearing his royal regalia, that includes the following :-

Royal robes heavily bedecked with pearls.

Monomakh’s cap or crown set with pearls and colored stones.

The royal scepter set with pearls and colored stones.

Portrait of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in the Hermitage Museum by unknown artist

Coronation regalia depicted on the portrait

The above portrait of Tsar Alexis I by an unknown artist depict him with the following coronation regalia

Coronattion robes heavily bedecked with colored stones and rows of pearls

A necklace with a cross hanging as pendant.

Monomakh’s cap or crown set with colored stones and rows of pearls.

The Orb set with colored stones and rows of pearls.

The royal scepter incorporating pearls at one end.

Tsar Alexis of Russia choosing his bride

The above painting of Tsar Alexis I choosing his bride, drawn by Grigory Sedov in 1882, over two hundred years after its occurrence, depicts the young Tsar Alexis choosing his bride before his marriage in 1648. Tsar Alexis I married Maria Miloslavskaya, who was four years his senior, and daughter of boyar Ilya Danilovich Miloslavsky, a relative of Boris Morozov. The six princesses depicted in the painting are all wearing a tiara or a headdress studded with pearls. At least two of them are depicted wearing multistrand pearl necklaces. Some of them are wearing drop earrings incorporating pearls. The dresses of at least two of the princesses are studded with pearls. The 19-year-old tsar is also depicted wearing a necklace incorporating pearls and a cap lined with pearls. The artist Grigory Sedov has attempted to recreate the mode of dressing and the type of ornaments worn by princesses in Russia two hundred years earlier, in the mid-17th-century. The expressions on the faces of the princesses in the painting are perfectly natural, and speaks of the artist’s ability in depicting the true nature of things in a bygone era.

Maria Ilynichna Miloslavskya – First wife (1648-1669) of Tsar Alexis I (1645-1676) and Tsaritsa consort of All Russia

Maria Miloslavskya was the first wife of Tsar Alexis of Russia, whom he married in 1648. Maria was four years senior to the tsar at the time of the marriage. The marriage turned out to be a happy one and produced 13 children in 21 years of marriage, out of whom two sons and six daughters survived into adulthood. The eldest son became Feodor III of Russia and the second son, Ivan V of Russia, who co-ruled with his half-brother Peter I of Russia. The third surviving dughter, Sophia Alekseyevna acted as regent to Peter I during his minority. Maria Miloslavskya died a few weeks after her 13th childbirth in 1669.

Portrait of Maria Miloslavskya drawn by Ivan Saltanov probably in the 1670s

Ornaments worn by the Tsaritsa –

A crown or headdress studded with pearls and colored stones.

A broad collar lined by a single row of pearls at its edges.

Broad bands studded with pearls and lined by rows of pearls at its edges, wrapped around each hand.

Natalia Kirillovna Naryshkina – Second wife (1671-1676) of Tsar Alexis I and Tsarina of All Russia

Two years after the death of his first wife, Tsar Alexis I decided to marry again, and took as his second wife, the 20-year-old Natalia Kirillovna Naryshkina , whom he married on February 1, 1671. Natlia was the daughter of a petty nobleman, Kirill Poluektovich Naryshkin, but was brought up in the house of the western-leaning boyar Artamon Matveyev who had married the Scottish-descended Mary Hamilton. The marriage produced three children, a son, who became Peter the Great of Russia and two daughters, out of whom only one survived into adulthood. Natalia was widowed when Tsar Alexis I died in 1676, but was treated with affection by her stepson Feodor, who ascended the throne as Tsar Feodor III of Russia. When Feodor III died in 1682, his brother Ivan V became co-Tsar with Natalia’s son Peter. Natalia acted as regent for Peter, who was still a minor, with her foster Artamon Matveyev serving as advisor. However, her regency was short-lived, as she was soon replaced by Feodor III’s elder sister, Sofia Alekseyevna, during the revolt of the Streltsy on May 15, 1682, in which two of her own brothers and her foster-father were killed, and her own father, Kirill Naryshkin was forced to take-up robes as a monk. Until August 1689, Natalia almost lived in poverty with her son, Peter the co-Tsar, in Alexei’s summer palace, about 5 km. from Moscow. Peter, who reached the age of 17 in August 1689, overthrew his half-sister Sofia, who had been ruling as an autocrat for 7 years in his name, and took control of his kingdom, and continued to rule as co-Tsar with his half-brother Ivan V. Sophia was forced to enter a convent, and Peter’s mother was restored to her rightful position as nominal leader of the court.

Portrait of Natalia Narishkina, second wife of Tsar Alexis I and mother of Peter the Great

In the above portrait of Natalia Narishkina drawn by an anonymous artist in the 18th-century, the former Tsaritsa is depicted almost dressed like a nun, and significantly without any ornaments decorating her person.

Feodor III Alexevich – Romanov Tsar of Russia from 1676 to 1682

Feodor was the eldest surviving son of Tsar Alexis I and his first wife, Maria Miloslavskya, and succeeded his father as Tsar in 1676 at the age of 15. Feodor was educated by the most learned Slavonic monk, Simeon Polotsky and thus possessed a fine intellect and noble disposition, eventhough he was disfigured and paralyzed by a mysterious disease from the time of his birth. Yet in spite of his physical disabilities he soon demonstrated that he was capable of ruling on his own, just as any other normal human being. A remarkable feature of his court was the lack of an oppressive atmosphere, leniency in the application of penal laws and a new sense of liberalism that pervaded his court. His notable achievements included the founding of the Academy of Sciences, and merit being made the main criteria for all appointments to the civil and military services, that replaced the former system of mestnichestvo, in which special preference was given to people of noble birth. Fedor III’s chief advisor in running the affairs of the state was Artamon Matveyev, foster father of Natalia Narishkina, mother of Peter I.

Tsar Feodor III took as his first wife an Ukranian noblewoman, known as Agaphia Simeonovna Grushevskaya, whom he married on July18, 1680. Feodor was 19 and Agaphia 17 at the time of their marriage. Agaphia was as learned as Feodor, and could speak and write languages like Polish, French and Latin. Agaphia turned out to be an angelic wife and Tsarina to Tsar Feodor, merciful and loyal to the disabled tsar and concerned about public welfare. She shared the radical views of her husband, and being well informed about western European life styles, she was the first to advocate beard-shaving and the use of western attire in the Russian court. She herself was the first tsarina to expose her hair and to wear a western dress in the Russian court.

She gave birth to her first child, a son, the expected heir to the throne on July 11, 1681, but unfortunately Agafya died three days later, due to complications of childbirth. Six days later, the nine-day old infant tsarevich also died, totally devastating Feodor III, who deeply mourned their passing away.

Portrait of Tsar Feodor III of Russia by unknown artist executed in the late 1600s

Coronation regalia depicted on the portrait :-

The above portrait of Tsar Feodor III of Russia, executed by an unknown artist, in the late 1600s depict the Tsar wearing coronation regalia. The components of the regalia, incorporating pearls are as follows :-

The Monomakh’s cap or crown heavily studded with pearls.

The coronation robe with its upper flap going round the shoulders, heavily studded with pearls.

The Orb depicted on the lower right-hand end of the portrait, also studded with rows of pearls.

A cross hanging as pendant from a necklace, probably made up of a double-strand of pearls.

Marfa Matveyevna Apraksina – Second wife (February 24, 1682 to May 7, 1682) of Tsar Feodor III and Tsarina of All Russia

Seven months after the death of his first wife, Feodor III took as his second wife Marfa Apraksina, daughter of Matvey Vasilyevich Apraksin, on February 24, 1682. However, just three months after this marriage, Feodor III died on May 7, 1682, at the age of 21, without a surviving issue, that sparked the Moscow uprising of 1682, as rumours spread that the Naryshkins in their desire to promote Natalia Naryshkin’s son Peter to the throne of Russia, strangled to death, the mentally and physically disabled Ivan, Tsar Feodor III’s younger brother, who was next in line of succession to the throne. The uprising subsided only when Ivan appeared in front of the rampaging crowds, to show that he was still alive and well.

Portrait of Marfa Apraksina by unknown author

Ornaments worn by the Tsarina :-

Headdress studded with pearls.

Drop earrings incorporating pearls.

Several necklaces around the neck, one of which appears to be a single-strand choker necklace, and the longest a multistrand pearl necklace, with a zig-zag lower strand.

Rings incorporating pearls.

Ivan V Alekseyevich Romanov – co-Tsar of Russia with his younger half-brother Peter I from 1682 to 1696

When the childless Feodor III died on May 7, 1682, a dispute arose between the families of his two wives, Miloslavsky and Naryshkin families, as to who should inherit the throne. Ivan, the second surviving son of Tsar Alexis I by his first wife, Maria Miloslavskya, was the next in line of succession to the throne, but was chronically ill and of infirm mind, and it was doubtful whether he had the mental ability for such a challenging task as ruling a vast country like Russia. Hence, the Boyar Duma (Council of Russian nobles) overlooked Ivan, and instead chose his half-brother, the ten-year-old Peter, Alexis I’s next son by his second wife, Natalia Narishkina, to be the next Tsar of Russia, with his mother appointed as regent. This arrangement was apparently ratified by the people of Moscow, but members of the Milolavsky family who were not happy with the decision of the Boyar Duma, spread the rumour that the Naryshkins had strangled to death, the mentally and physically disabled Ivan, in order to promote the chances of Peter, sparking off riots all over Moscow. The ambitious Sophia Alekseyevna, the third surviving daughter of Tsar Alexis I, then led a rebellion of the Streltsy, the Russian elite military corps, during which two brothers of Natalia Naryshkina and her foster father, Artamon Matveyev were killed, and her own father, Kirill Naryshkin was forced enter a monastery. The ultimate outcome of the uprising was that Ivan and Peter were proclaimed as joint Tsars, with Ivan being recognized as the senior of the two, and Sophia Alekseyevna replacing Natalia Naryshkina as Regent during the minority of the two tsars. Sophia ruled as an autocrat during the next seven years, in the name of both co-Tsars.

Ivan had a close relationship not only with his half-brother Peter, but also his stepmother Natalia Naryshkina. In fact he was not interested at all in becoming the Tsar, but was persuaded by his ambitious elder sister, Sophia Alekseyevna, who ruled as an autocrat in his name. In 1689, when Peter had turned 17, he planned to takeover power from his regent and half-sister Sophia, who was now unpopular due to two unsuccessful Crimean campaigns. When Sophia heard of Peter’s plans, she attempted to raise another riot, by misleading the Streltsy and the people of Moscow, that the Naryshkin’s had destroyed Ivan’s crown, and were about to set his room on fire. But the plan failed as Ivan himself declared his allegiance to his half-brother Peter, who had escaped in the middle of the night to the impenetrable monastery of Troitsky, from where he gathered his supporters and moved against Sophia, who was overthrown and forced to enter a convent. Peter I and Ivan V then continued there rule as co-Tsars, with Peter’s mother, Natalia Naryshkina being restored to her former position in court, exercing power on behalf of her son and stepson. Natalia died five years later in 1694, when Peter took complete control of his kingdom, with his brother Ivan V continuing nominally as a co-Tsar. When Ivan V died in 1696, at the age of 29 years, Peter became the sole ruler of his kingdom.

Portrait of Tsar Ivan V by unknown artist

Ornaments depicted on the portrait :-

A brooch rhomboidal in shape and studded with cabochon cut colored stones or black pearls.

A collar set with equally spaced large pearls in the center and lined at the edges by a single row of pearls.

Praskovia Saltykova – Wife of Tsar Ivan V and Tsaritsa consort of All Russia from 1684 to 1696

Two years after ascending the throne as co-Tsar, Ivan V married Praskovia Saltykova, the daughter of Fyodor Petrovich Saltykov, who was chosen by Ivan himself from an array of maidens parading before him. Ivan was 18 and Praskovia 20 years of age at the time of their marriage. Despite his physical and mental disabilities, Ivan’s marriage to Praskovia produced five robust daughters, one of whom would ascend the throne of Russia, as Empress Anna Ivanovna. However, by the age of 27, Ivan V was described by foreign diplomats, as senile, paralytic and almost blind. Ivan V died two years later, in 1696 at the age of 29 years.

After Ivan V’s death, Praskovia lived as a dowager Tsarina, holding court in Moscow and later Saint Petersburg, functioning as the first lady of the Russian court, as Peter had no legal wife at that time, until he officially married his second wife Catherine, at Saint Isaac’s Cathedral on February 9, 1712. Peter’s two daughters Elizabeth (future empress) and Anna (mother of future emperor, Peter III) were also educated at Praskovia’s court. Praskovia died in October 1723, a little over an year before Peter the Great’s own death in February 1725.

Portrait of Tsaritsa Praskovia Saltykova by artist Ivan Nikitin executed in the early 18th-century

Ornaments worn by the tsarina :-

A headdress or hairdo, incorporating three rows of large white spherical pearls on either side, and a single row of pearls radiating on either side of a centerpiece, set with colored stones.

Peter I the Great – Tsar of All Russia from 1682 to 1721 and later Emperor of All Russia from 1721 to 1725

Peter I who was co-Tsar with Ivan V from 1682 to 1696, became the sole Tsar of Russia after Ivan V’s death on February 8, 1696. Peter, who grew to become the tallest monarch in Europe during his period, with a height of 6 ft. 8 ins. also became one of the greatest Tsars in the history of Russia, assuming the title of Emperor of All Russia during the latter part of his rule from 1721 to 1725. His policy of expansion and modernization, learning from west European countries, eventually transformed the tsardom of Russia into a great empire not only in extent but also in terms of political power.

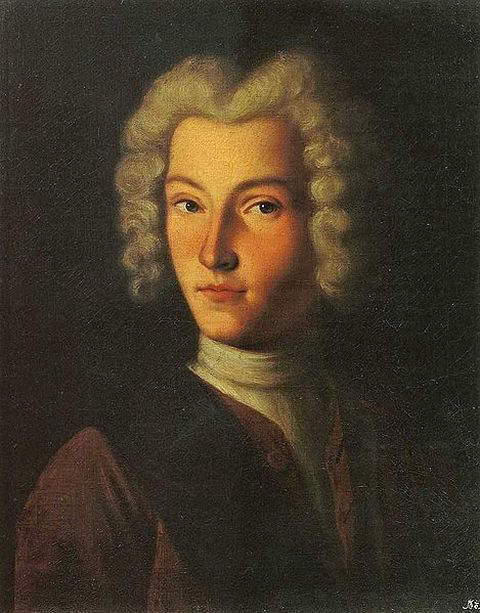

Portrait of young Peter the Great executed by unknown artist in the late 17th-century

Ornaments depicted on the portrait :-

A single-strand pearl necklace.

A large oval-shaped brooch set with colored stones and pearls, at the end of a V-shaped black garland, at the point where the outer red cloak splits, revealing the inner black robe.

Three smaller brooches on the red cloak in the space between the necklace and the black garland. These brooches are also set with colored stones and pearls

————————————————————————

Peter modernized the Russian army along western lines, and consolidated his authority by brutally suppressing all rebellions against his rule, going to the extent of disbanding the Streltsy, the Russian elite military corps, that always constituted a threat to any incumbent tsar. Russia had only one outlet to the sea, at the time he took control of the country, in the north on the White Sea at Arkhangelsk, whose harbour was frozen for nine months in a year. This was a serious limitation for the expansion of trade with the outside world and the setting up of a modern navy. Peter realized that possible outlets for his country were situated in the Baltic Sea in the north, which was under the control of Sweden and Black Sea in the south, controlled by the Ottoman Empire. After an unsuccessful attempt to capture the fortress of Azov from the Ottomans in 1695, he finally succeeded in July of 1696, and established the first Russian naval base at Taganrog in 1698.

In 1697 he undertook a journey to Europe with a large Russian delegation, visiting France, England, the Netherlands, Austria and cities such as Dresden and Leipzig, with the intention of forging a broad anti-Ottoman alliance, but received poor response, as there was little enthusiasm in Europe for such a move. However, Peter made use of this opportunity to learn first-hand about life in western Europe, and various skills such as shipbuilding in Amsterdam and the techniques of city building in Manchester, knowledge which he subsequently used in the building up of the Russian navy and the building of his new capital city at Saint Petersburg. During this tour he also engaged the services of shipwrights, seamen, builders of locks and fortresses, and others with useful skills, who would later follow him to Russia, and help build his country. Peter was forced to cut short his European tour and return to Russia, because of a rebellion by the Streltsy which was fortunately crushed even before he returned home. However, soon after his arrival in Russia, he executed over 1,200 rebels, disbanded the Streltsy and forced his half-sister Sophia, whom the Streltsy wanted to instal on the throne, to become a nun. It was during his visit to England in 1698, that Sir Godfrey Kneller painted Peter’s portrait in battle dress, that was subsequently presented to King William III of England.

Portrait of Peter the Great painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller during his visit to England in 1698

Ornaments depicted on the portrait :-

What looks like a single row of pearls, along the edges of a belt connecting the ends of the outer cloak, which too appears to be embroidered wirh rows of pearls.

————————————————————————-

Soon after his return from the West, Peter was determined to do away with age old Russian traditions and adopt west European customs. He ordered his courtiers and officials, either to trim their long beards or be clean shaven, and discard their robes and wear western attire. He abolished arranged marriages and encouraged men and women to select their own partners, resuting in more durable relationships. Towards the end of the year 1699, Peter ordered that new year should be celebrated in Russia not on September 1 but January 1, and that the old Russian calendar be replaced by the Julian Calendar with effect from January 1, 1700, which was year 7207 in the old Russian calendar.

Desirous of taking control of an outlet in the Baltic Sea, which was controlled by Sweden, Peter tried to forge an alliance with Sweden’s other enemies, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Denmark-Norway and Saxony. Peter’s first attempt to seize the Baltic coast ended in disaster in the Battle of Narva in 1700, in which the Russian army was badly defeated by the forces of Charles XII of Sweden. Having defeated the Russians, Charles XII directed his forces against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, giving Peter time to re-organize his army. As the war continued between Sweden and the Commonwealth, Peter began the construction of a new capitl city known as Saint Petersburg, named after St. Peter, the Apostle, in 1703, in a province of the Swedish empire which he had captured earlier, known as Ingermanland. As construction of the new capital continued, in 1707, Peter secretly married Martha Skavronskaya, who converted to Orthodox Christianity and took the name Catherine. In 1706, after suffering repeated defeats at the hands of Charles XII, the Polish king August II abdicated. Charles then invaded Russia, hoping to march towards Moscow, and defeating Peter’s army on the way, at Golovchin in July, 1708. However, Charles’ army was stopped at the next encounter at Lesnaya, by Peter’s forces, who inflicted heavy losses on Charles’ forces, after stopping Swedish reinforcements from reaching them. Charles then abandoned his march to Moscow, and instead invaded Ukraine. Peter then made a tatical withdrawl to the south of Ukraine destroying everything that could assist the Swedes, along their way. Deprived of local supplies, in the winter of 1708-1709 the Swedish army was forced to halt its advance, but resumed again in the summer of 1709. On June 27, 1709, Peter’s forces intercepted the Swedish army at Poltava, resulting in a battle in which the Swedish forces were routed, and forced Charles to seek refuge in the Ottoman empire.

Portrait of Peter the Great by artist Jean-Marc Nattier executed around 1710

Description of above portrait :-

Peter the Great is depicted on the above portrait, wearing battle dress and holding a staff in his right hand, that rests on his helmet, and his left hand holding the hilt of a gem-studded sword.

————————————————————————

Having defeated Charles XII, Peter restored August II to his throne in Poland, and diverted his attention towards the Ottoman empire, initiating the Russio-Turkish war of 1710. However, Peter’s campaign in the Ottoman empire proved to be disastrous, forcing him to sign a treaty in which he had to return the Black seaports seized in 1697, and guarantee safe passage to Charles XII back to Sweden. Peter’s northern armies then captured the Swedish province of Livonia, driving the Swedes into Finland. The Russian naval fleet then inflicted a defeat on the Swedish fleet at the Battle of Gangut in 1714, and the Russians occupied most of Finland. In his confrontation with Charles XII, Peter also obtained the assistance of the electorate of Hanover and the kingdom of Prussia, but Charles XII refused to yield. In 1718, Charles XII was killed in battle, and Sweden which was at war with all its neighbours, made peace with them by 1720, except Russia. Peace with Russia finally came in 1721, by the Treaty of Nystad, that ended the Great Northern War, and Russia was granted four provinces south and east of the Gulf of Finland, and Peter secured the much wanted access to the sea.

Immediately after peace was made with Sweden, in recognition of his conquests, Peter was officially proclaimed Emperor of All Russia on October 22, 1721 and the Russian Tsardom officially became the Russian Empire. During the last years of his rule he introduced reforms in the Russian Orthodox Church, replacing the Patriarchate with a collective body known as the Holy Synod, a council of ten clergymen. He replaced the Council of Nobles, known as the Boyar Duma, with a nine member Senate, which became the supreme council of state. He divided the country into new provinces and districts, and enhanced tax revenues, by placing tax collection under the overall supervision of the Senate. He created the famous “Table of Ranks” a new order of precedence, in which merit and service to the emperor were criteria instead of birth, that deprived most of the boyars of their high ranks and positions. He introduced compulsory education in the sciences and mathematics, for the children of nobility, and all government officials including clerical staff. In 1724, Peter had his second wife, Caherine, crowned as Empress of All Russia, although he still remained the actual ruler. This was a move on his part to ensure a smooth succession after his death, as all his male issues had predeceased him, including his eldest son, Alexei by his first wife Eudoxia, who was tortured and killed on Peter’s orders in 1718, because the boy had disobeyed him and opposed his policies.

Peter the Great died on February 8, 1725 of Uremia, at the age of 52 years, having reigned for 42 years, 28 years as sole ruler and 14 years as co-ruler with his half-brother Tsar Ivan V.

Diamond Order of Peter the Great

The above Diamond Order of Peter the Great is studded with diamonds of different sizes, shapes and cuts, mostly preserving the original natural facets and characteristic octahedral crystalline shapes.

Eudoxia Lopukhina – First wife of Tsar Peter I of Russia and Tsaritsa Consort of All Russia from 1689 to 1698

Peter the Great married his first wife, Eudoxia Lopukhina in 1689, soon after he wrested power from his half-sister and regent, Sophia Alekseyevna in August of that year. The marriage was arranged by his mother, Natalia Naryshkina, who was restored to her former position in court by Peter, after being ignored and living in isolation for seven years during Sophia’s regency. Eudoxia was senior to Peter by two years, at the time of her marriage, and was chosen by Natalia mainly because of Eudoxia’s mother’s relationship to the well known boyar Fyodor Rtishchev. Eudoxia was crowned Tsarina of All Russia soon after her marriage. Eudoxia gave birth to her first child Tsarevich Alexi Petrovich in 1690. She gave birth to two more sons, Alexander and Paul in 1692 and 1693. Out of the three children only Tsarevich Alexi Petrovich survived into adulthood, and was the next in line of succession to the throne. However, their marriage soon ran into trouble, aggravated by Eudoxia’s conservative relatives, whom Peter hated. Peter soon abandoned Eudoxia and took a Dutch beauty, Anna Mons as his mistress.

In 1697, just before Peter embarked on his European tour, he asked his Naryshkin relatives to persuade Eudoxia to enter a monastery, which she refused. However, soon after Peter returned from his European tour in 1698, he decided to end his unhappy marriage, by divorcing Eudoxia and forcing her to enter the intercession convent of Suzadal. Eudoxia who entered the convent, managed to live there as a lay person and even find a lover by the name of Stepan Glebov, who was executed by quatering when the tsar was informed of the relationship. Eudoxia and her son and heir apparent Tsarevich Alexi Petrovich, soon became the center of opposition to Peter’s reforms, around whom disgruntled Church officials rallied. Tsar Peter soon brutally suppresses this opposition, putting his son and former wife on trial, executing all bishops who supported them, and transferring Eudoxia to another convent in Ladoga. Tsarevich Alexi Petrovich suspected of plotting to overthrow his father, confessed on torturing, and was convicted and sentenced to be executed. But, Peter was hesistant in authorizing his execution, and the tsarevich died in prison, probably of injuries suffered during his torture.

when Catherine I, Peter’s second empress consort, ascended the throne after, Peter’s death, Eudoxia was secretly moved to the Shlisselburg fortress in St. Peterburg, but in 1727, when Eudoxia’s grandson, Peter II ascended the throne, Eudoxia was released from incarceration, and returned to Moscow with great pomp and pagentry, where she kept her own court at the Novodevichy Convent, unitl her death in 1731.

Portrait of Eudoxia Lopukhina by artist Pintor Desconhecido in the 18th-century

Marfa Skavronskaya later Catherine I of Russia – Unofficial second wife from 1703 to 1712 and Official second wife and Tsaritsa/Empress consort of Peter the Great from 1712 to 1725. Empress of Russia from 1725 to1727