History of the spread of the knowledge of the value and appreciation of pearls from the Persian Gulf region to countries of the west, initially to Greece and Rome, and subsequently to other western nations in the medieval period

Pearls were undoubtedly first discovered and appreciated in the Persian Gulf region, and the knowledge of their value and appreciation subsequently spread to the west, through Greece and Rome

In the webpage dealing with the “History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls – the Organic Gem Perfected by Nature – Page 1” it was shown without any ambiguity that pearls were first discovered and came to be appreciated in the East or the Orient. Several lines of evidence, both historical and archaeological were presented that consolidated this view, the most significant among which was the fact that historically the most ancient sources of pearls in the world, such as the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, were the same regions where some of the earliest human civilizations began, such as the ancient Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia, “the cradle of human civilization” and the ancient Egyptian civilization. It appears that the discovery and appreciation of pearls went hand-in-hand with the development of ancient human civilizations. The oldest pearls identified in the Persian Gulf region, a single pierced-pearl and mother-of-pearl artifacts comes from As-Sabiyah, Kuwait, dating back to the late stone age, 6,000-5,000 B.C.E. (7,000-8,000 B.P.). Another solitary pearl belonging to the same period was found among human remains at a site in Umm al-Quwain. A third single pierced-pearl near a female chin and mother-of-pearl pendants dating back to 5,200-4,200 B.C.E. (7,200-6,200 B.P.) was recovered from a site in Jebel al-Buhais, in Sharjah. Other ancient pearls ranging in age from 4,000-1,000 B.C.E. (6,000-3,000 B.P.) were also discovered from sites in Oman, Iraq, Bahrain, Iran, Kuwait and Palestine. These areas where the discoveries were made were part of the ancient Sumerian (5,900-2,350 B.C.), Akkadian (2,350-2,193 B.C.), Babylonian (2,100-1,600 B.C.) or Assyrian empires (2,000-1,800 B.C.). and the age of the pearl or pearl jewelry discovered roughly coincide with the period of these ancient civilizations. Burial of people with a pierced pearl in their right hands appear to be a common custom prevalent during these ancient periods. Thus, without any doubt the Persian Gulf region, appears to be one of the regions where pearls were first discovered and came to be appreciated. This webpage is dedicated to the history of how the knowledge of the appreciation of pearls initially spread from the Persian Gulf to the countries of the west such as Greece and Rome, where such appreciation reached unprecedented levels, and subsequently spread to other nations in Europe in mediaeval times, where the use of pearls became closely identified with the monarchies, and to cater to the increase in demand for pearls, apart from the traditional sources of the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, new sources of pearls were discovered by Columbus in America in 1498, which were then thoroughly exploited by the Spanish. The esteem with which pearls were held, by the monarchies, the rich and the well-to-do, made them the most valuable and sought after commodity since the beginning of the Christian era, and was considered more valuable than gold, a status quo that prevailed into modern times, with Cartier purchasing its multistoried headquarters in New York in 1916 for the value of just a single two-strand pearl necklace valued at $1.2 million.

The use and appreciation of pearls first spread to ancient Egypt after the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C.

The antiquity of the Persian Gulf fishery was also authenticated by other sources of archaeological evidence, such as cuneiform inscriptions, from Nineveh in ancient Assyria, and the writings of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, geographers and travelers, such as Theophrastus (371-287 B.C.), Megasthenes (350-290 B.C.), Androsthenes (300-400 B.C.), Nearchus (360-300 B.C.), Pliny (23-79 A.D.), Isidore of Charax (1st-century A.D.), Ptolemy (90-168 A.D.), and the unknown Alexandrian Greek author (1st-century A.D.) of the “Periplus of the Erythrian Sea.” The use and appreciation of pearls spread to ancient Egypt only after the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C. by Cambyses II, that lasted until 332 B.C. During this period in Egypt it is believed that the pearl resources of the Red Sea, another ancient source of pearls, were exploited to their full extent.

Knowledge of the use and appreciation of pearls was acquired by the Greeks from Persia and Egypt after Alexander the Great captured the Persian empire between 334 and 331 B.C.

Alexander the Great’s successful campaigns in the east, that led to the capture of the vast Persian empire, extending from Egypt to the Indus river in India, between 334 and 331 B.C. following the defeat of the troops of Darius III, exposed the Greeks to oriental products such as pearls, to which the Persians attached a premium value and used in ornamentation. Such knowledge of the use and appreciation of pearls was acquired not only in Persia, where many of Alexander’s officers and soldiers settled down after taking Iranian wives, but also in Egypt, which was under Persian rule from 525 B.C. to 332 B.C. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. Ptolemy I a Macedonian Greek General of Alexander the Great, took control of Egypt and founded the dynasty of the Ptolemies ruling from their new capital in Alexandria. Under the Ptolemies, the city of Alexandria showcased the power and prestige of Greek rule. Alexandria became a seat of learning and culture, centered around its famous library. The use of pearls reached a new dimension in the courts of Alexandria at the height of its power, from 323 B.C. to 30 B.C. Cleopatra was the last of the Ptolemies who was installed as the undisputed ruler of Egypt by Julius Caesar in 47 B.C. following a civil war and power struggle between her and her brothers. Caesar married Cleopatra by whom he had a son, Caesarion. After the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. Cleopatra married Caesar’s friend Mark Antony, and ruled Egypt until 30 B.C. when she and Mark Antony committed suicide after the defeat of their forces by the Romans led by Octavius, who took over power as Augustus Caesar, the first Roman emperor. The well known episode of Cleopatra dissolving a pearl worth 30 million sesterces in a glass of vinegar, which she subsequently consumed, in fulfilling a bet she had taken with Mark Antony, as reported by Pliny, reveals the extent to which pearls were held in esteem in Egypt in the 1st-century B.C., though the story itself lacks credibility. The courts of the Ptolemies in Alexandria were well known for the lavish use of pearls, and the court of Cleopatra was no exception.

Knowledge of the use and appreciation of pearls spread from the Greeks to the Romans during the 1st-century B.C.

Romans used the Greek word “margarita” or the Latin word “unio” for pearls

From the Greeks, the knowledge of the use and appreciation of pearls spread to the Romans, who referred to pearls by the Greek name, “margarita” and the more common Latin name, “unio.” Pliny (23-79 A.D.) was of the view that the word “unio” was derived from the word “unique” as every single pearl had unique properties that was different from any other pearl. However, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus (330-395 A.D.) believed that the word “unio” was given because each pearl was found singly in a shell. The French classical scholar, Claude de Saumaise, believed that the name “unio,” the common name for “onion” was given to the pearl, because of its laminated construction like onions. According to Pliny, the Roman usage of the words “unio” and “margarita” connotes two different kinds of pearls; “unio” referring to larger, more attractive, high-quality pearls and “margarita” referring to smaller, less attractive, low-quality pearls.

Military campaigns of Julius Caesar in the West and Gnaeius Pompeius Magnus in the East in the 1st-century B.C.

Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.), the Roman military and political leader, initially shared power with Gnaeius Pompeius Magnus (106-48 B.C.) and Marcus Licinius Crassus in the First Triumvirate. Both Julius Caesar and Pompey undertook military campaigns on behalf of the republic, and emerged victorious, raising their profile as powerful military and political leaders. Julius Caesar conquered Gaul, that extended the Roman empire to the North Sea and in 55 B.C. conducted the first Roman invasion of Britain. Pompey in the meantime conducted military campaigns in Sicily, the Mediterranean Sea and Africa, that ensured the grain supplies of Rome and eliminated the threat of piracy in the Mediterranean. He then conducted successful military campaigns in the East between 64-63 B.C. against Pontus, Syria, Phoenicia, and Armenia, extending the Roman empire to a distance of over 200 miles east of the upper Euphrates.

Pompey’s campaign against the wealthy kingdom of Mithridates VI in 64-63 B.C. resulted in the capture of large quantities of pearls that served to enrich the treasury of Rome and strengthen its economy

Pompey’s campaign in the East, that preceded that of Julius Caesar in the West, particularly against the wealthy kingdom of Mithridates VI of Pontus, resulted in his armies capturing large quantities of war booty, that were subsequently taken to Rome, and displayed ostentatiously during his triumphal re-entry into Rome. Among the treasures displayed in the triumphal procession in 61 B.C. in which pearls played a prominent part, were 33 crowns encrusted with pearls, numerous pearl ornaments, a large portrait of Pompey himself rendered in pearls and a grotto or shrine dedicated to the muses and decorated with pearls. Pearls were considered the most expensive of all treasures around this time, and the capturing of large quantities of pearls in the eastern campaign, was regarded as a indicator of the success of Pompey’s military campaign, and helped to elevate his profile as a successful military commander. The pearls captured in this campaign served to enrich the treasury of Rome and strengthen its economy.

Julius Caesar’s military invasion of Britain in 55 B.C. is believed by many historians to have been prompted by his desire to take control of the freshwater pearl resources of Scotland

Likewise Julius Caesar’s military invasion of Britain five years later in 55 B.C. is believed by many historians, to have been prompted by his desire to take control of the freshwater pearl resources of Britain, particularly those of Scotland which was famous for its freshwater pearls. Pearls together with gold underpinned the Roman currency during this period, and an increase of pearl reserves helped to strengthen the empire’s currency.

The transfer of the treasures of Alexandria to Rome after the capture of Egypt in 30 B.C.

The fall of Egypt to Roman armies led by Augustus Caesar in 30 B.C. and the capture of its capital Alexandria, led to the transfer of the wealth and treasures of Alexandria to Rome, a significant part of which constituted pearls.

The appreciation of pearls reach unprecedented levels in the Roman empire

Pliny’s sarcasm on the excessive use of pearls by womenfolk of Rome during his period

The great esteem in which pearls were held in the Roman empire, and the enormous value attached to them, which according to Pliny was ranked first in value among all precious things, led to an increase in demand for these valuables among the rich and the powerful, and especially among their womenfolk who yearned to possess them. The wealthy Romans not only wore ornaments set with pearls, but also pearl-embroidered dresses, that led Pliny to write sarcastically, “It is not sufficient for them to wear pearls, but they must trample and walk over them, and the women wore pearls even in the still hours of the night, so that in their sleep they might be conscious of possessing the beautiful gems.

Martial’s criticism of the unwarranted esteem in which pearls were held by the womenfolk of Rome

The extravagance of the rich womenfolk of Rome at that time, drew sharp criticism from writers of the period, such as Martial, Tibullus, Seneca and Horace. Martial, referring to a woman named Gellia, wrote, “By no gods or goddesses does she swear, but by her pearls. These she embraces and kisses. These she calls her brothers and sisters. She loves them more dearly than her two sons. Should she by some chance lose them, the miserable woman would not survive an hour.”

Seneca’s stinging criticism of the way pearl earrings were designed during his period

Seneca, criticizing the way pearls were used in ear ornaments, wrote, “Pearls offer themselves to my view, simply one for each ear. No! the lobes of our ladies have attained a special capacity for supporting a great number. Two pearls alongside of each other, with a third suspended above, now form a single earring ! The crazy fools seem to think that their husbands are not sufficiently tormented unless they wear the value of an inheritance in each ear !”

Julius Caesar intervenes and restricts the use of pearls by women

The extravagancy of the womenfolk became so serious, that Julius Caesar himself had to intervene, and interdict their use by women beneath a certain rank.

Extravagance of some Roman emperors in the use of pearls

Emperor Caligula who reigned between 12-41 A.D. was famous for granting a consulship to his favorite horse Incitatus, which he decorated with a valuable pearl necklace. He is reported to have worn slippers embroidered with pearls, and Philo, the Jewish ambassador to Emperor Caligula wrote, “The couches upon which the Romans recline at their repasts shine with gold and pearls; they are splendid with purple coverings interwoven with pearls and gold.”

It was also reported that tyrannical Emperor Nero, who ruled between 37-68 A.D. had his throne and scepter decorated with pearls. He also provided the actors in his theatre with masks and scepters decorated with pearls.

The extraordinary prices quoted for some quality pearls

Pearls were considered as extremely valuable during this period and the prices recorded for some of the choicest pearls by writers of this period give an indication of the great esteem and value in which they were held. Suetonius wrote that the Roman general Vitellius paid the expenses of a military campaign with the proceeds of one pearl from his mother’s ears. Such was the great value placed on pearls, that Pliny wrote in the 1st-century A.D. that they ranked first in value among all precious things, and reported that the value of the two famous pearls, which Empress Cleopatra wore at the celebrated banquet to Mark Antony was worth 60 million sesterces. Suetonius also reported that the value of the pearl presented by Julius Caesar as a tribute of love to Servilia, the mother of Brutus, was 6 million sesterces. Another writer Aelius Lampridius reported that an ambassador who called on the Emperor Alexander Severus presented two large drop-shaped pearls to the empress. However, the emperor instead of giving the pearls to his empress, decided to offer them for sale. But, since no purchaser could be found for such valuable pearls, the emperor ordered that the pearls be hung from the ears of the statute of Venus, saying that “If the empress should have such pearls, she would set a bad example to other women, by wearing an ornament of so much value that no one could afford to buy.”

The Greeks and Romans were end-users of the pearls produced in the Orient and were ignorant of the pearl fisheries taking place in these regions

Even though the ancient Roman and Greek writers were familiar with pearls and their properties and the characteristics that distinguished a good quality pearl from a medium or poor quality one, they hardly knew anything about the origin of pearls, and the pearl fisheries held annually in the seas where they were found. Pliny and Aelianus depended on Megasthenes, the Greek geographer and writer and later ambassador to the court of the Mauryan king Chandragupta, in Pataliputra, India, between 350 and 290 B.C., for information on the pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Mannar. In his work “Indica” he wrote about the pearl fishery of Madurai and Taprobane (Ceylon), and gave a curious story about pearl oysters living in communities like swarms of bees and governed by one single oyster remarkable for its size and great age, and protecting the smaller oysters in the community, so that the fisherman first made an attempt to catch this oyster, making it easy to catch the others. It is not known from where Megathenes got this misinformation, but if had visited the fishery on the Gulf of Mannar during his stay in India, he would not have committed to writing such a glaring untruth. Pliny and Aelianus repeated the curious story on the pearl oysters, quoting the “Indica” written by Megasthenes. This curious story on pearl oysters despite its inaccuracy has a historical significance, in that it confirms that the Greeks and Romans were actually the consumers or end-users of pearls, which were produced in the Orient thousands of kilometers away. Hence the ignorance of the Greeks and Romans on the pearl fisheries of the Orient.

Specimens of pearls and pearl ornaments from the Greek and Roman periods still in existence

Several specimens of pearls and pearl ornaments belonging to the Classical Greek period (6th-4th century B.C.), the Hellenistic period of Greece (323 B.C.- 31 B.C). and Roman periods (27 B.C.- 476 A.D.), are still in existence and in a fairly good state of preservation in some of the museums in the United States, Russia, Britain, France and other European capitals. The following is a list of such specimens :-

1) A 3rd-century B.C. Greek necklace made of pearls and gold, probably belonging to the Hellenistic period, in an excellent state of preservation, residing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

2) Several pearl earrings preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Hermitage Museum at St. Petersburg, the British Museum in London and the Louvre Museum in Paris.

3) A beautiful Tyszkiewicz bronze statuette of Aphrodite in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, with a pearl earring in each ear, consisting of a single pearl in a fairly good state of preservation, suspended by a spiral thread of gold passing through the pearl and the lobe of the ear. The statuette considered as the most beautiful bronze Venus known, is believed by some to belong to the Classical Greek period (500 B.C – 336 B.C.) and others to the Hellenistic period (323 B.C – 31 B.C.).

4) An artistic representation of pearl grape earrings shown on an intaglio of the bust of Athene Parthenos of Phidias, by Aspasios, preserved in the Gemmen Munzen Cabinet in Vienna since 1669.

Why pearls and pearl ornaments of antiquity are relatively few in comparison to crystal gems, coins and gold jewelry of the same period?

Considering the popularity of pearls and pearl ornaments in Greece and Rome from the 6th-century B.C. to the 5th-century A.D. and the large collections accumulated by the aristocracy, only a few specimens from this period are still in existence. In comparison coins, gold jewelry, crystal gems from this period, which were more durable are found in abundance. Pearls being organic in origin and less durable than crystal gems have not survived the long periods of pillage, waste and burial in the earth. This explains the relatively few specimens of pearls and pearl ornaments of this period that are found in archaeological collections and art museums, and the somewhat decayed and dull appearance of such specimens.

The case of the Stilicho pearls that demonstrated the decay of pearls due to ravages of time and burial

An instance of the decay of pearls caused by long periods of burial was well documented in the early 16th-century. The daughters of the famous Roman general Stilicho, who were successively betrothed to the Emperor Honorius, died in 407 A.D. and were buried with their pearls and ornaments. In the year 1526, more than one thousand one hundred years later, during excavations for an extension of St. Peters, the tomb was identified and opened. It was found that the metal ornaments worn by the women were in a fairly good state of preservation, but the pearls used in ornaments had turned dull and lusterless and were in a advanced state of decay. This was one of the well-documented cases of decay of pearls over long periods of burial.

The sources of pearls that satiated the appetite for pearls in the Roman empire

The Persian Gulf was one of the sources of pearls that supplied the Roman Empire, and reference to the Persian Gulf pearl fishery were made by several Greek and Roman geographers, travelers and writers of the period

The unprecedented demand for pearls in the Roman Empire between 27 B.C. and 476 A.D. was met by supplies originating from the traditional sources of pearls in ancient times, such as the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar. During the Hellenistic period of Greece (323 B.C. – 31 B.C.) and the period of the Roman Empire (27 B.C. – 476 A.D.) numerous references were made to the pearl industry based around the Island of Tylos (Bahrain) in the Sinus Persicus (Persian Gulf), by Greek and Roman geographers, travelers and writers of the period. The Greek Philosopher Theophrastus wrote in 315 B.C. that pearls came from the waters off the coast of India and certain islands in the Red Sea and the Sinus Persicus (Persian Gulf). Androsthenes and Nearchus, who explored the eastern Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf during the period of Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.), reported about the pearling Island of Tylos (Bahrain) in the Persian Gulf and the Island of Stoidis in the Strait of Hormuz. Pliny in his 1st-century A.D. book “Historalis Naturalis” referred to the pearl fisheries at Tylos (Bahrain) and Catifa (Al-Qatif) and said, “But the most perfect and exquisite pearls of all others be they that are gotten about Arabia within the Persian Gulf. Isidore of Charax, a Greek geographer, wrote in the 1st-century A.D. that “in the Persian Gulf is found a certain island, where pearls are found in abundance.” The certain island referred to by Isidore is believed to be the Island of Bahrain around which the most lucrative pearl banks were situated. Ptolemy, the Alexandrian Roman geographer and astronomer wrote in the 1st-2nd century A.D., that a thriving pearl fishery existed from time immemorial around the Island of Tylos (Bahrain) in the Persian Gulf. The “Periplus of the Erythrian Sea” written by an unknown Alexandrian-Greek author in the 2nd-half of the 1st-century A.D. refers to a place not far beyond the mouth of the Persian Gulf, where there were many pearl fisheries. The fact that the Greek and Roman geographers, travelers and writers of the Hellenistic period and the period of the Roman Empire, were well acquainted with the Persian Gulf pearl fishery, provides indirect evidence for the Persian Gulf as a source of pearls during this period.

How supplies of pearls from the Persian Gulf reached the Roman Empire?

Supplies of pearls from the Persian Gulf reached the Roman Empire either by land or the sea route. During the period of the Roman Empire, Roman ships from ports in the Red Sea were sent out to the Persian Gulf and across the Indian Ocean to the Gulf of Mannar, in quest of pearls, one of the most treasured commodities in the Roman empire, not only for ornamentation but also like gold a valuable reserve that strengthened the currency of the Roman empire. The ships sailed along the Arabian coast past Yemen and Oman and entered the Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz, and sailed to the Island of Tylos (Bahrain) where purchases were made, before returning by the same route.

Pearls from the Persian Gulf also reached the Roman Empire through the medium of Jewish, Syrian and Armenian traders along the land route through northern Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Greece.

The Gulf of Mannar was another source of pearls that supplied the Roman Empire, and reference was also made to this pearl fishery by writers of the period

The Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery was also a prolific source of pearls, that supplied the pearl-hungry Roman Empire between 27 B.C. and 476 A.D. Greek and Roman geographers, travelers and writers of this period also referred to this pearl fishery. Pliny the Elder, in the 1st-century A.D. referred to the Gulf of Mannar pearl fishery, as the most productive of all fisheries in his famous book “Historia Naturalis.” Ptolemy, the 2nd-century A.D. Alexandrian-Roman geographer and astronomer referred to the rich pearl-fishing grounds near the Island of Epidorus (Mannar) in Taprobane (Sri Lanka), a land also famous for its variety of gemstones, such as beryls, rubies and sapphires. The most detailed account of the pearl fishery of the Gulf of Mannar, comes from the Periplus of the Erythrian Sea, by the unknown Alexandrian-Greek author of the 1st-century A.D. The account describes a sea-journey undertaken in the 1st-century A.D. that explored the coastal areas of southern India, the Malabar coast in the west and the Coromandel coast in the East. Reference is made to the domain of the Pandyan kingdom.; the region known as “Paraha” occupied by the Parawa community, who were professional pearl divers and fisherman; Kolkhoi (Korkai) the second largest city in the Pandyan kingdom and the center of the pearl fishery on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar; Komar (Cape Comorin) at the tip of the Indian sub-continent; the “Coast Country” beyond Kolkhoi, a reference to the pearl fishery coast and Argaru, a center for piercing pearls.

Direct evidence for the thriving trans-Indian Ocean trade between the Roman empire and the Pandyan kingdom of South India and the Sinhalese kingdom of Sri Lanka comes from Strabo, the Greek traveler, historian and geographer

It is from Strabo, the Greek traveler, historian and geographer, we have direct evidence of the thriving trans-Indian Ocean trade between the Roman Empire and the Indian sub-continent and Sri Lanka, that employed about 120 vessels during the time of Augustus Caesar (27 B.C.- 14 A.D.), originating from Myos Hormos, the Roman port on the western shores of the Red Sea, and making use of the seasonal monsoonal winds. Strabo also reported about the arrival of an Indian Embassy in Egypt, from king Porus of the Pandyan kingdom, on their way to pay their respects to Emperor Augustus Caesar, carrying several gifts that included a collection of pearls. During the period 14 A.D. to 361 A.D. nine Roman emperors are believed to have received embassies from India or Sri Lanka.

The Roman empire’s eastern trade with India, accounted for 50% of the annual trade of the empire, worth about 50 million sesterces. A significant part of this trade was on pearls originating from the Gulf of Mannar, for which there was an unprecedented demand in the Roman empire. Apart from pearls, other commodities included in the trade, were spices, pepper, ivory, ebony, sandalwood, muslin and precious stones.

Popularity of pearls in the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium, whose capital was Constantinople

The knowledge of the use and appreciation of pearls reached Byzantium and Greece in the 4th-century B.C. long before it reached the Western Roman empire

The unprecedented demand for pearls that was seen in the Western Roman empire, with its capital at Rome, was also a feature of the Eastern Roman empire or Byzantium, with its capital at Constantinople. In fact the use and appreciation of pearls reached Byzantium and Greece, long before it reached the Western Roman empire and Rome, following the military campaigns of Alexander the Great against the Persian empire between 334 and 331 B.C. The Eastern Roman empire was mainly Greek-speaking as opposed to the Western Roman empire, which was mainly Roman-speaking. In 324 A.D. Emperor Constantine of the Eastern Roman empire transferred the capital from Nicomedia in Anatolia to Byzantium on the Bosphorus, which came to be known as Constantinople or “New Rome,” and was well positioned astride the trade routes that passed through the Baltic and the Mediterranean, linking the East and the West. After the collapse of the Western Roman empire in 476 A.D. the emperors of Byzantium considered themselves the successors of the Western Roman empire, and entertained hopes of re-conquering Rome occupied by the Goths.

Justinan I, the greatest of the Byzantine rulers who was a prolific builder and a patron of learning, art and literature

Justinian I, also known as Justinian the Great, who reigned between 527 and 565 A.D. was the greatest of the Byzantine rulers who sought to revive the greatness of the Roman empire, and re-conquer the lost western half of the classical Roman empire. But, he was only partially successful in recovering the territories of the Western Roman empire, including the city of Rome itself. The greatest legacy left behind by Justinian I, was the revision and uniform compilation of Roman Law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. He was a prolific builder, who built the famous Hagia Sophia, which became the center of Eastern Orthodox Christianity for many centuries. Other architectural masterpieces of his period include, the Church of Holy Apostles; the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, featuring two famous mosaics representing Justinian and his empress Theodora. Learning, art and literature also flourished during his period. After the pillage of Rome by the Goths, who also plundered its treasures, including large collections of pearls and pearl ornaments, the Byzantine empire with Constantinople as the capital, became the focus of all arts, and pearls were the favorite ornaments of the aristocracy.

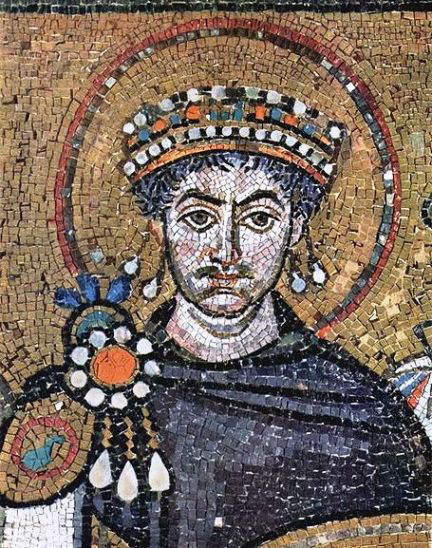

Mosaic at Basilica of St. Vitale in Ravenna showing Emperor Justinian I

The popularity of pearls in the Byzantine period is seen in the mosaics depicting Emperor Justinian 1 and Empress Theodora in the basilica of San Vitale

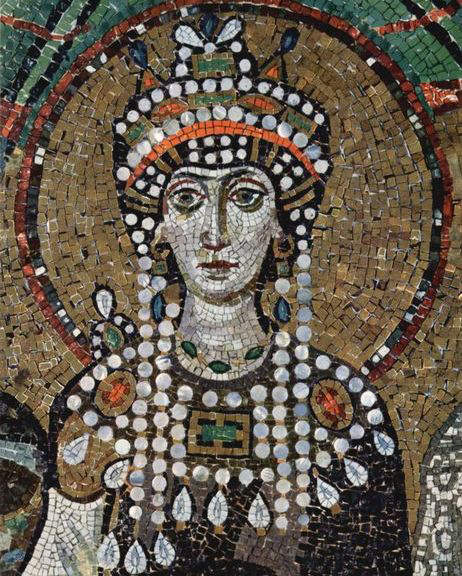

The popularity of pearl ornaments during this period, is shown in the famous mosaic in the basilica of San Vitale depicting Justinian with his head covered with a jeweled cap, consisting of at least two rows of pearls, and two drop-shaped pearls on either side, appearing to hang from it, and what looks like a corsage hanging from one side of his shoulder, with an orange-colored crystal gem in the center, surrounded by a row of near-spherical pearls, with three drop-shaped pearls hanging from it. Empress Theodora is shown in a mosaic in a standing posture wearing a tiara encircled by two rows of pearls, and at least two strings of pearls hanging down from it up to the region just below her chest, and wearing a long robe embroidered with pearls in the chest region.

Ravenna mosaic showing Empress Theodora and her attendants

Empress Theodora in a mosaic at St. Vitale in Ravenna.

Another evidence for the popularity of pearls in the Byzantine period are the coins minted during the period of different emperor’s showing them wearing diadems, collars and necklaces etc. incorporated with pearls

Depiction of Byzantine emperors in coins from around 330 A.D. to 1204 A.D. when Constantinople was captured and pillaged by Venetian and Latin adventurers during the 4th-crusade, show them wearing diadems, collars, necklaces etc. incorporating pearls, providing another source of evidence for the great quantity of pearls used by them.

The following tremissis and coins of the period of Emperor Justinian, show him wearing a diadem or jeweled cap incorporating strings of pearls, and pearl drops hanging from them.

1) Tremissis of Emperor Justinian show him wearing a head covering with two strings of pearls and two drop-shaped pearls hanging from behind.

Tremissis of Emperor Justinian I

2) Justinian was one of the first emperors to be depicted wielding a cross on the obverse of a coin. The emperor is shown wearing a diadem incorporating strings of pearls, and a pair of drop-shaped pearls hanging from it on either side of his face.

Coin of Emperor Justinian showing him wielding a cross

3) A gold coin of Justinian excavated in India, probably in the South, providing evidence for the thriving Indo-Roman trade during that period(527-565 A.D.). The emperor is shown wearing a diadem incorporating strings of pearls, and a pair of drop-shaped pearls hanging from it on either side. As in the previous coin the emperor is shown wielding a cross.

Gold Coin of Justinian I excavated in South India

The oldest existing crown in the world, the Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen incorporating pearls is of Byzantine workmanship having features of Byzantine crowns.

The oldest existing crown in the world, believed to have been created during the reign of King Bela III of Hungary, between 1172 and 1196, has strong Byzantine influence, as the king himself was brought up in the Byzantine court, and was for sometime the official heir to the Byzantine throne. The crown known as the “Holy Crown of Hungary” or the “Crown of Saint Stephen” is identical to the Kamelaukion-type of crowns with closed tops first introduced in the Byzantine empire. The lower diadem known as the Corona Graeca, being decorated with enamel pictures is also a typical feature of Byzantine crowns. The crown has three parts :- 1) the lower diadem (Corona Greca) 2) the upper intersecting bands (Corona Latina) 3) the cross on the top. Four hanging pendants dangling from chains are situated on each side of the diadem, with a single dangling chain on its back.

Holy Crown of Hungary- Crown of St. Stephen

The Holy Crown of Hungary provides indirect evidence for the extensive use of pearls in the 12th-century in the Byzantine empire

The crown is made of gold and the Corona Graeca, which is 5.2 cm wide and has a diameter of 20.5 cm, is decorated with 19 enamel pictures, with two rows of pearls on either side. The Corona Latina is made up of two intersecting bands of gold 5.2 cm wide, arising from the upper edge of the Corona Graeca and welded at the top to the edge of a square central panel 7.2 cm wide, decorated with a square cloisonne enamel picture depicting Christ Pantokrator. The bands were also decorated like the Corona Graeca, with the pictures of Christ’s apostles, with two pictures of standing apostles in each band, making eight apostles, as listed in Acts 1.13. There are twelve pearls on the square-shaped central panel and 60 pearls on the bands, making a total of 72 pearls on the Corona Latina, symbolizing the number of Christ’s disciples, according to Acts 10.1. The crown is also known as the “Crown of St. Stephen” as according to legend, Stephen I, the first king of Hungary, who was later canonized as St. Stephen, was crowned as king using this crown, which was sent by Pope Sylvester II. The Crown of St. Stephen was the coronation crown of the kingdom of Hungary, which was used for the coronation of more than 50 kings in the history of Hungary. The Hungarian coronation insignia consists of the Holy Crown, the scepter, the orb and the mantle. The 12th-century “Holy Crown of Hungary” of Byzantine origin, incorporating pearls, provides indirect evidence for the extensive use of pearls in the Byzantine empire during that period.

Coronation Insignia of Hungary

Photo: CSvBibra cc

Enormous treasures plundered from Rome in 410 A.D. eventually ended-up in the Citadel of Carcassone of the Visigothic kings in 453 A.D.

With the downfall of the Roman empire in the fifth-century A.D. and the pillage and plunder of Rome, the accumulated treasures of Rome, that included gems and jewelry and large collections of pearls, were carried away by the conquering Goths, and scattered among the great territorial lords of western and northern Europe. The Visigoths and Ostrogoths were the two main branches of the Goths, who were among the Germanic peoples that spread through the late Roman empire. The Visigoths first emerged as a distinct people in the Balkans in the 4th-century, from where they participated in several wars with Rome. It was a Visigothic army under Alaric I, who first invaded Italy and sacked Rome in 410 A.D., pillaging and plundering its enormous treasures, part of which were believed to be jewels from the Temple of Jerusalem, previously plundered by the Romans during the sacking of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

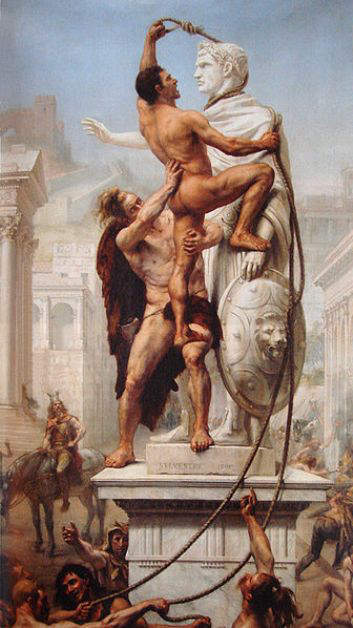

Sack of Rome by Visigoths in 410 A.D.

Citadel of Carcassone

Photo: cc

The Visigoths were eventually settled in southern Gaul as a foederati of the Romans, but soon the Visigoths asserted their independence and established their own kingdom with its capital at Toulousse. Narbonne also developed as another major city in southern Gaul, under the Visigoths. The Visigothic king, Theodoric II, attacked and captured the well fortified Citadel of Carcasonne, situated near Narbonne in southern Gaul, from the Romans in 453 A.D. Theodoric II built more fortifications at Carcassone, converting it to an almost impregnable fortress, that subsequently was able to withstand several assaults by the Franks in the early 6th-century. In the year 462 A.D. the Romans officially ceded the Citadel of Carcassone to Theodoric II, and the enormous treasures plundered from Rome in 410 A.D. eventually came to be lodged in this mighty citadel.

The plunder of Narbonne and Toulouse after Visigoths were expelled from southern Gaul by Clovis I, the first Frankish king in 507 A.D.

The rule of the Visigoths in southern Gaul was cut short in 507 A.D. at the Battle of Vouille, when they were defeated by the Franks under Clovis I. However, In 508 A.D. the Visigoths successfully foiled attacks by the Frankish king Clovis on the well fortified Citadel of Carcasonne, in Septimania. Thus, Clovis I, the first king of all Franks was able to establish Frankish hegemony over most of Gaul, after expelling the Visigoths from southern Gaul, except Septimania. In his campaign against the Visigoths the Franks, sacked and pillaged the main cities of Narbonne and Toulouse in southern Gaul, carrying away the treasures in the same way the Visigoths and Ostrogoths carried away the treasures of Rome. The kingdom of the Visigoths was now limited to Hispania, with Septimania, the only territory north of the Pyrenees held by them.

Visigothic rule confined to Hispania with Barcelona and later Toledo as capital, and continued until the arrival of the Moors in 711 A.D

The center of Visigothic rule shifted first to Barcelona and then inland and south to Toledo. In 531 A.D. Childebert I, one of the four sons of Clovis I, who was the Frankish king of Paris, received a plea from his sister, Chrotilda, wife of King Amalaric of the Visigoths, that her husband, the Arain king of Hispania, was grossly mistreating her, a Catholic. Childebert I mobilized an army against the Gothic king Amalaric, who was defeated and killed in Barcelona. The churches of Barcelona were sacked by Childebert’s army. In another expedition against the Visigoths in 542 A.D. he took possession of Pamplona and besieged Zaragoza, but was forced to retreat. During this expedition he brought back to Paris a precious relic, the tunic of Saint Vincent, in honor of which he built at the gates of Paris, the famous monastery of St. Vincent.

Statuette of Childebert I from the monastery of St. Vincent in Paris

Votive Crown belonging to Visigothic King Recceswinth

Visigothic rule continued in Hispania until 711 A.D. when finally the kingdom collapsed when their king and most of their leading men were killed in the Battle of Guadalete, by a force of invading Arabs and Berbers. Visigothic crowns and crosses and other beautiful objects of their period of rule are still in existence in the Musée de l’Hôtel de Cluny, Paris, and the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, out of which the most beautiful is the votive crown belonging to Visigothic king Recceswinth, who ruled between 653 and 672 A.D. Button-shaped, white pearls appear to be the predominant gemstones on this crown, placed in symmetrical positions around the colored gemstones.

The Franks of the Merovingian dynasty become the successors to the Western Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic religion becomes the main religion of western Europe

The Frankish kingdom of the Merovingian dynasty, founded by Clovis I became the dominant political force in Western Europe from the 6th to 8th centuries, effectively becoming the successor to the Western Roman Empire that collapsed in the late 5th-century A.D. The baptizing of Clovis I and 3,000 of his soldiers in 496 A.D. led the Frankish aristocracy and people converting to the Roman Catholic religion, which eventually became the dominant religion in Western Europe by the end of the 8th-century A.D. The Merovingian dynasty of Frankish rulers was replaced by the Carolingian dynasty in 751 A.D. founded by Pepin the Short, that ruled western and central Europe until 843 A.D.

Statute in the Cathedral of Reims showing baptism of Clovis by Saint Remi in 496 A.D.

The splendor of the courts of early Frankish kings like king Dagobert and the great treasures of jewels collected in the churches

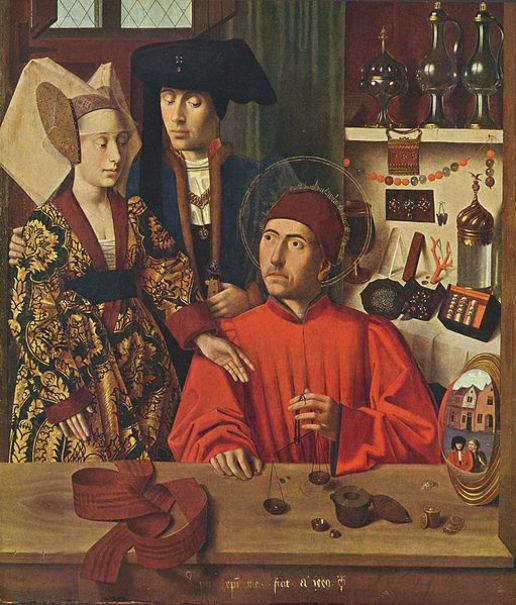

The military successes of the Franks in the 6th and 7th centuries A.D. led to the accumulation of treasures of jewels that enriched the palaces of the kings and their great churches. The people of Gaul under Frankish rule developed a taste for objects of art, rich costumes and personal decorations, and the demand for such items were met by the trade carried on by Jewish and Syrian merchants. The courts of some of the early Frankish kings rivaled in magnificence even those of the oriental monarchs of Persia and India. One such king was King Dagobert I, the king of all Franks from 629 to 639. who ruled from Paris, and built the famous Altes Schloss in Meersburg (in modern Germany), and the Saint Denis Basilica, where he was buried after his death. Dagobert raised his skilful jeweler, Eligius to the bishopric of Noyon, and later appointed him as his chief adviser. Eligius under the name of St. Eloi (Saint Eligius), became one of the most popular saints in Gaul. It is said that under the supervision of Saint Eligius, the artistic bishop, the ancient churches, received shrines, vestments and reliquaries, decorated with pearls and other gems. Since the time of Saint Eligius for several centuries, the greatest treasures of jewels appear to have been collected in the churches.

Representation of Dagobert I on gold coin minted at Uzes

Legend of Saint Elgius by Petrus Christus

The use of pearls and other gemstones in enriching coronation regalia advanced greatly during the reign of Emperor Charlemagne (768-814 A.D.)

Charlemagne (Karlmein) meaning “Charles the Great” was the greatest of the king of Franks, who ruled between 768 A.D. and 814 A.D., belonging to the Carolingian dynasty and the son of the founder of the dynasty, Pepin the Short (751-768 A.D.). He transformed the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of western and central Europe, including Italy. He was crowned Emperor of the Romans, by Pope Leo III in December 800 A.D. The Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of art, religion and culture through the medium of the Catholic Church, associated with his reign, encouraged the formation of a common European identity, uniting most of Western Europe for the first time since the Romans, leading many historians to consider him as the “father of Europe.”

Charlmagne wearing the sacred regalia

During the reign of Charlemagne the use of gems and pearls in enriching the coronation regalia, vestments and reliquaries in Europe advanced greatly, and the sacred regalia of Emperor Charlemagne are among the most remarkable pieces preserved among the imperial treasures in Vienna. The above portrait by Albrecht Durer show him wearing the gem-studded coronation vestments and regalia. Out of these, it is the Crown of Emperor Charlemagne that incorporates the greatest number of pearls. In fact, pearls are the predominant gemstones in this crown, which though smaller, are interspersed symmetrically around the other colored gemstones, contributing to the overall beauty of the crown.

From the 7th to 11th centuries pearls and other valuable gems and jewels were offered at churches by the faithful. leading to the build-up of treasures of jewels in the churches of western Europe

Since the time of Saint Eligius (Eloi) in the 7th-century A.D. pearls and other valuable gems became objects of offering at the churches by the penitent and fear-stricken subjects. As Kunz and Stevenson put it in the “Book of the Pearl,” “The heart of man, filled with the love of God, laid its earthly treasure upon the altar in exchange for heavenly consolation. Pious faith dedicated pearls to the glorification of the ritual; altars, statutes, and images of the saints, priestly vestments, and sacred vessels were surcharged with them.” The practice continued well into the 11th-century, and during this period the greatest treasures of jewels appear to have been collected in the churches of Western Europe.

Accumulation of pearls in the treasuries of churches led to an alternative and artistic use of pearls in decorating the covers of bindings of sacred manuscripts

With large quantities of valuable pearls accumulating in the churches, an alternative and artistic use for pearls developed during this period, that involved the use of pearls and gold, in the rich and elegant bindings of the splendidly written missals and chronicles, finished in the highest degree of excellence at great expense. The art of writing manuscripts and binding them into books, with their covers enriched with gold, pearls and colored stones developed into an exacting art, that an artist might sometimes devote his whole life to completing a single manuscript. It is said that Julio Clovio took nine years to paint 26 miniatures in the Breviary of the Virgin, presently in the royal library at Naples. A monk of St. Andoen is said to have labored for 30 years to produce the large missal in the library at Rouen. Several of this superbly bound manuscripts are still in existence, such as in the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice; in the treasury of the cathedral at Milan and among the Imperial Russian collections in Moscow.

The Ashburnham manuscript of the Four Gospels with an elegantly designed cover decorated with colored stones and 98 freshwater pearls

The Ashburnham manuscript of the Four Gospels, that was once the property of J. P. Morgan is a remarkable specimen of the elegantly bound manuscripts that originated in western Europe between the 7th-11th centuries. The manuscript belonged to the Abbey of the Noble Canonesses, founded in 834 A.D. at Lindau on Lake Constance. Careful examination of the manuscript by Alexander Nesbit led to the conclusion, that the rich cover of the manuscript was probably designed and executed between 896 and 899 A.D. by order of Emperor Arnulf of the Carolingian dynasty of Frankish kings. The elegantly designed cover of this manuscript is an interesting example of the jeweler’s art of this period, and one of the few remaining pieces of the magnificent ecclesiastical jewelling of that period.

The elegantly designed cover of the Ashburnham manuscript of the Four Gospels, enriched with gold, colored stones and pearls,

The cover is made up of gold, colored stones, and pearls. There are around 98 pearls on the cover, most of them freshwater pearls probably originating from rivers in Europe. Freshwater pearls were re-discovered from the rivers of Scotland, Ireland, France and the headwaters of the Danube, probably during the 7th-11th centuries, after Julius Caesar’s invading legions discovered them for the first time and carried them in large quantities to Rome in the 1st-century B.C. The river pearls did not have the luster and orient of saltwater pearls originating from the Orient, nevertheless due to the ease with which they were obtained, they were used extensively in ecclesiastical decorations, the principal use of pearls in western Europe from the 7th-11th centuries. This explains the use of freshwater pearls in the elegantly designed cover of the Ashburnham manuscript.

The colored stones incorporated in the cover are most probably oriental in origin; the red stones probably Ceylon rubies or spinels from Badakshan, and the green stones, emeralds probably from India, the only sources of these gems during the 9th-century.

Pearls used by the successor states to the Western Roman empire, controlled by the Visigoths, Ostrogoths and the Franks in the decoration of coronation regalia etc. of monarchs appear to have come from enormous treasures plundered from the Roman empire

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 A.D. the thriving trans-Indian ocean trade between it and the ports of southern India and Sri Lanka, a significant portion of which constituted pearls originating from the Gulf of Mannar, came to a halt. However, the trade with the Eastern Roman empire continued as seen from the coins of Emperor Justinian unearthed in southern India. Likewise, pearls originating from the Persian Gulf reached only the Byzantine empire, but not the successor states to the Western Roman empire, controlled by the Visigoths, Ostrogoths and later the Franks. Hence, the pearls used by the Visigoths, Ostrogoths and the Franks, in the decoration of the regalia of monarchs, vestments, reliquaries etc., most probably came from the enormous treasures plundered during the declining years of the Roman Empire, including the infamous sacking of Rome in the year 410 A.D. In the successor states to the Roman Empire pearls were not a priority and did not receive the great esteem and appreciation afforded to them by the rich and the powerful, especially their womenfolk, as in the Roman empire. Thus, the popularity of pearls in personal ornamentation in the Frankish empire controlled by Emperor Charlemagne, that constituted western and central Europe had declined to a great extent, and the status quo continued after the death of Emperor Charlemagne, when internal dissensions, separations, and division of the empire into nations of Europe destroyed commerce and impoverished the arts. However, as pointed out earlier, pearls and pearl ornaments were offered by the faithful at the altar for the glorification of the churches and their rituals.

The popularity of pearls in personal decoration in Europe increased mainly after the returning crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries

The popularity of pearls in personal decoration in Europe only increased after the returning crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries, who had seen the esteem in which they were held in the invaded countries of Byzantium and Arabia, and returned not only with riches of pearls, gold and precious stones, but also acquiring the latest knowledge of the decorative arts from the Moorish and Byzantine craftsmen. In England, though pearls well known and valued in ancient times, they do not seem to have been much used before the 12th-century. By the 13th and 14th centuries pearls became very popular as personal ornaments throughout Europe, and were worn both by men and women, as ornaments and as decoration or embroidery on their formal dresses, on all occasions, be it a marriage, the consecration of a bishop, the celebration of a victory in battle or a famous sporting event. Around this time diamonds and colored stones were not popular as ornaments in Europe, as faceting of crystal gems was not known. The only type of cutting and polishing known at that time for crystal gems was perhaps cutting en cabochon, which was used in the setting of only royal regalia such as crowns, diadems, scepters etc. The popularity of pearls in ornamentation since ancient times, was mainly due their ready-made finish, at the time of their discovery in oysters, with a natural luster and brilliance, that does not require any human intervention.

During the middle ages, kings, emperors, princes and nobles carried their valuables into the battle field, where they were easily lost or destroyed

During the middle ages, the tradition had been for kings, emperors, princes and nobles to carry their valuables, such as pearls, diamonds and other precious stones into the battle field as ornaments or fixed onto their battle dress, due to the strong belief held by them on the mysterious power of precious stones. In fact jewels constituted a large portion of their portable wealth, and hence kings, emperors, nobles and knights usually went into battle superbly arrayed. As a result of this practice valuable treasures were easily lost or destroyed on the battle field. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why only a few personal ornaments of the monarchy of this period have been preserved up to this time.

The lavish use of pearls in the 14th and 15th centuries by the monarchies of Europe

The lavish use of pearls in the 14th and 15th centuries was reported among the noble and royal houses of Europe, such as the Ducal Houses of Burgundy, Bavaria, the noble houses of Valois and Anjou of France, and the sovereigns of England and Scotland. The greatest lovers of pearls in the Ducal House of Burgundy were Philip the Bold (1342-1404), the fourth and youngest son of King John II of France; Philip the Good (1396-1467), the Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death in 1467, whose court was the most extravagant in Europe at that time and during whose reign Burgundy reached the height of its prosperity and prestige and a leading center of arts; and Charles the Bold (1433-1477) the son of Philip the Good and Isabella of Portugal, who succeeded his father as Duke of Burgundy, from 1467 to 1477.

Philip the Bold – Duke of Burgundy 1342-1404

Philip the Bold in later life

Philip the Good – Duke of Burgundy – 1396-1467

Portrait of probably Isabella of Portugal, wife of Philip the Good

Charles the Bold – Duke of Burgundy – 1433-1477

In the year 1473, when Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, one of the wealthiest and most powerful nobles in Europe at that time, attended the Diet of Treves, to negotiate the terms of the marriage of his only daughter and heiress apparent, Mary, to Maximilian, son of Emperor Frederick III, he was accompanied by 5,000 splendidly equipped horseman, and Charles himself was attired in a cloth of gold garnished with pearls valued at 200,000 golden florins. However, due to the mutual distrust of both parties the negotiations did not produce the desired results.

Lavish use of pearls at the historic Landshut Wedding in Bavaria in 1475

The historic Landshut wedding that took place in the medieval period in 1475, in Bavaria was another occasion that saw the lavish use of pearls. The marriage that signified a strong alliance between Poland and Bavaria against the Ottoman Turks, was between George the Rich, the Duke of Bavaria and Hedwig Jagiellon, daughter of King Casimir IV of Poland. The marriage took place in St. Martin’s Church, Bavaria, and was officiated by the Archbishop of Salzburg. Soon after the marriage ceremony, the bridal procession proceeded through the old town to the Town Hall. Around 10,000 people who attended the wedding were provided with food and drink by the young duke’s father. The occasion has gone down in history for its lavish use of pearls not only by the wedded couple, but also by the invited guests. Among the ornaments worn by Duke George was a pearl chaplet valued at 50,000 florins, which the duke wore on his hat and a clasp worth 6,000 florins. Today, the historic Landshut Wedding is commemorated every four years in Landshut, Bavaria, in which more than 2,000 participants in mediaeval costumes, bring the festival to life to recreate the late middle ages.

Duke George the Rich of Bavaria

Princess Hedwig Jagiellon, daughter of King Casimir IV of Poland

One of the most remarkable pieces of pearl decoration in the 15th-century was the headdress of Margaret of Denmark, Queen of Scotland

The famous 1483-portrait of Margaret of Denmark, wife of King James III of Scotland, by Hugo van der Goes, now preserved at Hampton Court depicts the queen wearing wonderful pearl ornaments, of which her pearl-studded head-dress is considered today as one of most remarkable pearl decorations of the 15th-century. It is quite possible that some of the pearls used in her ornaments were actually freshwater pearls that originated in the rivers of Scotland.

Margaret of Denmark, Queen Consort of Scotland (1469-1486)

Pearl-studded headdress of Queen Margaret of Scotland

In the 16th-century pearls were used by Henry VIII of England to enrich the appearance of his court

In England in the 16th-century, Henry VIII (1491-1547), the second monarch of the House of Tudor, well known for his role in the separation of the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church, and taking six wives in his desperate desire for a male heir, used pearls lavishly in enriching the appearance of his court as well as his queens. Portraits of Henry’s wives by Hans Holbein (1497-1543) depict them wearing elaborate pearl ornaments and decorations as seen below.

Catherine of Aragon – 1st wife of Henry VIII

Anne Boleyn – 2nd wife of Henry VIII

Jane Seymour – 3rd wife of Henry VIII

Anne of Cleves – 4th wife of Henry VIII

Catherine Howard – 5th wife of Henry VIII

Catherine Parr – 6th and final wife of Henry VIII

The use of pearls by the clergy in the 16th-century

Hans Holbein’s portraits show the use of pearls not only by the monarchy but also by members of the clergy as well. For eg. in his 1527 portrait of William Warham (1450-1532), the Archbishop of Cantebury, the pearl-encrusted miter of the Archbishop is also depicted in the background.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, with his pearl-encrusted miter in the background

Following the discovery of pearls in the New World by Christopher Columbus towards the end of the 15th-century, international attention on the pearl industry shifted to the New World for the next one and half centuries

In 1498, following the discovery of pearls by Christopher Columbus on his third voyage to the New World, off the Island of Cubagua, near Venezuela, the hub of the international pearl industry which was hitherto based around the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, shifted to the New World. Subsequently, other sources of pearls were also discovered in the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), and off the Pacific coast of Panama. The Spanish conquistadors soon exploited these vast pearl resources, and in fact pearls became the first natural resource of the New World, that brought in large returns for the colonizers, especially the Spanish, whose empire was enriched for the next two centuries, by the great wealth obtained from the industry. Until the development of mines to exploit other natural resources of the New World, such as gold, silver and emeralds, in regions such as Mexico, Peru and Colombia, the value of pearls exported from the New World exceeded that of all other exports combined together. According to Humboldt, until the year 1530, the average annual returns from pearls exceeded 800,000 piastres.

The increase in international production of pearls in the two-centuries following the discovery of the New World fisheries, coincided with an unlimited extravagance in personal decoration in the European courts leading to an unprecedented demand for pearls

Throughout the 16th-century and until the mid 17th-century, the intensive exploitation of the pearl resources of the New World, by the Spanish, led to an increase in international production of pearls, providing Europe with large quantities of pearls, to satisfy the unprecedented demand generated by the extravagance in personal decoration, not only of the European courts, but also by persons of rank and fortune. The pearl fishery in the Gulf of California, based in Baja California, became the only source of high-quality black pearls in the world, for which their was great demand among the monarchies of Europe.

Pearl ornaments used by the spouses of Austrian Hapsburg rulers from 1612 to 1780

The evidence for the extravagant use of pearls in the European courts during the 16th and 17th centuries come from paintings and engravings of the time, and especially portraits of members of the royal family, belonging to the various ruling dynasties of Europe, such as the Hapsburgs, the Valois, the Medicis, the Borgias, the Tudors, and the Stuarts. Perhaps the largest treasures of pearls were in the possession of the Hapsburg dynasty, one of the most important royal houses of Europe, that provided all the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors from 1438 to 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian and Spanish empires and several other countries. The following portraits of the spouses of Austrian Hapsburg rulers, who were Archdukes of Austria and Holy Roman emperors, from Ferdinand I (1556-1564)) to Archduchess Maria Theresa (1740 to 1780), show the extent to which pearls and pearl ornaments were used during this period.

Anne of Bohemia and Hungary – Wife of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor (1556-1564)

Anne of Bohemia and Hungary – wife of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor

Ornaments worn – Necklace with a centerpiece consisting of an oval-shaped colored stone and drop-shaped white pearl.

Three drop-shaped pearls on a hat ornament.

A gold chain.

Pearl ear-drops.

Maria of Spain – Wife of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor (1564-1576)

Maria of Spain – Wife of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor (1564-1576)

Ornaments worn – Pearl ear-drops.

Double-stranded pearl rope as necklace and vertical loop hanging from it.

Anna of Tyrol – Wife of Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor (1612-1619)

Anna of Tyrol – wife of Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor (1612-1619)

Ornaments worn – tiara set with pearls, stomacher with a drop-shaped pearl hanging from it.

Portrait by – Frans Pourbus the Younger

Maria Anna of Bavaria – Wife of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1619-1637)

Maria Anna of Bavaria – wife of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1619-1637)

Ornaments worn – Pearl necklaces, pearl-studded brooches

Portrait by – Joseph Heintz the Elder (1564-1609)

Eleonora Gonzaga – Wife of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1619-1637)

Eleonora Gonzaga – wife of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1619-1637)

Ornaments worn – pearl necklace, pearl ear-drops, pearl strands around the head.

Portrait by – Frans Luycx

Maria Anna of Spain – Wife of Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor (1637-1657)

Maria Anna of Spain – wife of Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor (1637-1657), with her son in 1634

Ornaments worn – two strands of pearls forming a V-shaped decoration over the upper part of her dress.

Pearls encrusted on the baby’s dress.

Portrait by – unknown artist

Claudia Felicitas of Austria – Wife of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor (1658-1705)

Claudia Felicitas of Austria – wife of Leopold 1, Holy Roman Emperor (1658-1705)

Ornaments worn – Pearl necklace made of perfectly spherical pearls, that looks like a choker under the modern classification of pearl necklaces.

Pearl ear-drops and stomacher with three drop-shaped and three spherical pearls.

Portrait by – Unknown artist

Eleonor Magdalene of Neuburg, Wife of Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor (1658-1705)

Eleonor Magdalene of Neuburg, wife of Leopold 1, Holy Roman Emperor (1658-1705)

Ornaments worn – Single strand pearl necklace, pearl ear-drops, stomacher with a single large drop-shaped pearl and pearl bracelets or bangles on both hands

Portrait by – Unknown artist

Maria Theresa (1740-1780) – Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia – Wife of Francis I Stephen, Holy Roman Emperor

Maria Theresa at the age of 10 years

Ornaments worn – Pearl ear-drops.

Stomacher set with colored stones and pearls.

a V-shaped pearl belt

Portrait by – Andreas Moller

Maria Theresa (1740-1780) – Archduchess of Austria, wife of Francis 1, Holy Roman Emperor

Ornaments worn – Pearl ear-drops, pearl-studded hair decoration

Pearl-studded crown on one side of the portrait

Portrait by – Martin van Meytens

The Pearl-Studded Imperial Crown of the Austrian Empire made in 1602

The Imperial Crown of the Austrian Empire made in 1602 by order of Archduke Rudolph II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1576 to 1612

Rudolph II, Archduke of Austria and Holy Roman Emperor (1576-1612)

Pearl ornaments used by the spouses of the kings of the House of Valois-Angouleme in France

The House of Valois, that provided the kings of France from 1328 to 1589, were descendants of Charles of Valois, the fourth son of King Philip III of France, who reigned from 1270-1285. Portraits of the spouses of Valois-Angouleme kings from Francis I (1515-1547) to Henry III (1574-1589), reveal the great esteem in which pearl ornaments were held by the monarchy of Europe during this period.

Eleanor of Austria – Wife of King Francis I of France (1515-1547)

Eleanor of Austria, wife of King Francis I of France (1515-1547)

Ornaments worn – Pearl ear-drops, three drop-shaped pearls in each earring.

Pearl head band with a drop-shaped pearl hanging from each side.

Pearl-studded necklace.

Pearl embroidered neckline on the dress.

Portrait by – Joos van Cleve

Catherine de Medici – Wife of King Henry II of France (1547-1559)

Catherine de Medici – Wife and Queen consort of King Henry II of France (1547-1559)

Ornaments worn – Pearl-studded head band, pearl earrings, pearl embroidered bodice of dress, with clusters of pearls around the neck and across the chest and shoulders.

Portrait by – Miniature attributed to Francois Clouet in 1555

Mary, Queen of Scots – Wife of King Francis II of France (1559-1560)

Francis II of France (age 15) with his wife Mary, Queen of Scots (age 17) soon after Francis ascended the throne in 1559

Ornaments worn – Pearls incorporated on the crowns of both the king and queen.

Single strand of pearls worn as a head band by the Queen.

Pearl ear-drops worn by the Queen.

Pearl strand and clusters of pearls around the collar of her dress.

Pearl decorations on the bodice of her dress.

Portrait by – Francois Clouet

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1567)

Ornaments worn – Strings of pearls as head band

Pearl ear-drops

Long rope of pearls around the collar, knotted in front, and the remaining part of the rope hanging vertically downwards from the knot

Portrait by – Unknown artist after Francois Clouet

Mary Stuart at the age of 13

Ornaments worn – Pearl incorporated head bands.

Pearl ear-drops; single strand of pearls around the neck in the bodice of her dress.

Long rope of pearls on the bodice of her dress, forming a W-shaped decoration, with the remaining part of the rope hanging from the depression in the center.

Portrait by – Francois Clouet in 1555

Elizabeth of Austria – Wife of Charles IX of France (1560-1574)

Elizabeth of Austria, wife of Charles IX of France (1560-1574)

Ornaments worn – Pearls incorporated on the head band

Clusters of pearls on the band around her neck on the bodice of her dress.

Clusters of pearls across her chest.

Pearls incorporated intermittently on the loops of the bodice, with a drop-shaped pearl hanging from the center.

Pearls incorporated intermittently on the hands of her dress.

Portrait by – Francois Clouet

Louise of Lorraine – Wife of Henry III of France (1574-1589)

Louise of Lorraine – Wife and Queen Consort of Henry III of France (1574-1589)

Ornaments worn – Two-strand pearl necklace.

Three drop-shaped pearls on the forehead.

Strands of pearls as loops and double-strand hanging from the center on the bodice of her dress.

Clusters of pearls across the chest.

Portrait by – Unknown artist

The use of pearl ornaments by Tudor Kings or their spouses

The use of pearls by the wives of King Henry VIII, the second monarch of the House of Tudor, was already dealt with in detail elsewhere on this webpage.

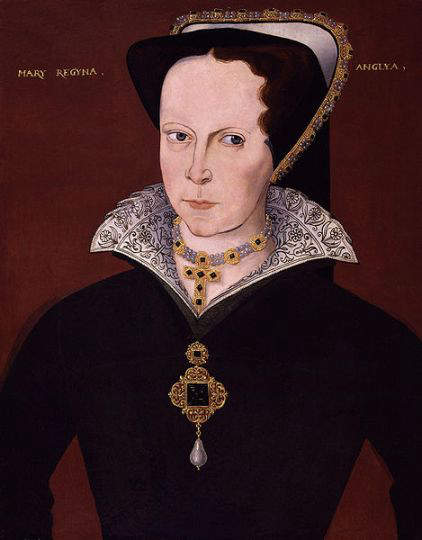

Mary 1 – Fourth Monarch of the Tudor dynasty

Miniature portrait of Mary Tudor (Mary 1) at the time of her engagement to Charles V in 1522

Ornaments worn – Pearl rope twisted into a double strand.

Head band with single strand of pearls

Portrait by – Lucas Horenbout

Mary 1 in 1544

Ornaments worn – Head band with single strand of pearls.

Head band with clusters of pearls.

Belt encrusted with pearls.

Necklace with pearls and colored stones.

Portrait by – Master John

Mary I in 1554

Ornament worn – A jeweled pendant bearing the famous drop-shaped pearl known as La Peregrina, set beneath two diamonds

Portrait by – Hans Eworth

Queen Mary 1 around 1555 wearing the pendant bearing the famous La Peregrina pearl

She is also shown wearing a choker composed of alternating pearls and colored stones, whose centerpiece is a cross set with colored stones.

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Elizabeth I – 5th and the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty

Elizabeth 1 was the 5th and the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty, during whose rule the use of pearls in projecting the image of the monarchy was carried to new heights unprecedented in the history of any monarchy in Europe. The following portraits of the great queen done at different periods in her life time provides ample evidence for this view.

Elizabeth I of England and Ireland – Darnley Portrait (1575)

Ornaments worn – Two-strand pearl necklace, pearl incorporated tiara

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Elizabeth I as Princess around 1546

Ornaments worn – Long pearl rope twisted twice around the neck as necklace, with a centerpiece containing three drop-shaped pearls.

Single pearl strand as head band.

Strand of clusters of pearls interspersed with colored stones, as a second head band.

Stomacher of colored stones with three drop-shaped pearls.

Band of alternating clusters of pearls and colored stones as a border for the neckline.

Band of alternating clusters of pearls and colored stones as a sagging belt.

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Elizabeth I as Princess around 1546

Ornaments worn – A band of colored stones and pearls around the neck.

A second band of colored stones with a single row of pearls on either side, the lower row interspersed with drop-shaped pearls.

A V-shaped bands of alternating pearls and colored stones around the hip.

Coronation scepter with three spherical pearls mounted at its end.

Coronation crown studded with colored stones and pearls.

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Full length portrait of Elizabeth 1 by Steven van der Meulen around 1563

Ornaments worn – Pearl strands as head band.

Long double-stranded pearl rope around the hip.

Stomacher with a drop-shaped pearl.

Armada Portrait of Elizabeth 1 commemorating the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588

Ornaments worn – Seven-strand pearl necklace.

Pearl embroidered dress.

Pearl embroidered robes around the shoulders.

Pairs of drop-shaped pearls mounted on the headdress.

Crown mounted with pearls and colored stones in the background.

The Queen’s hand rests on a globe symbolizing her international power

Portrait by – George Gower

Portrait of Elizabeth 1 being Carried in Procession around 1600

The Queen wears a pearl embroidered dress with rows of pearls along the edges of the hands and the V-shaped front piece. Pearls are also incorporated in her elaborate hair-do. A brooch attached to one hand has colored stones and a drop-shaped pearl incorporated on it. The gem-studded white dress with an elaborate collar and hair-do, gives an out-of-the-world, fairy like appearance to the great queen.

Portrait by – Robert Peake the Elder

Use of pearl ornaments by the Stuart Kings of England

Anne of Denmark, spouse of first Stuart King of England, James I (1567-1625)

Anne of Denmark – Wife of King James I of England

Ornaments worn – Double-strand pearl necklace.

Pearl ear-drops.

Strand of pearls along the edge of neckline.

Drop-shaped pearl hanging from forehead.

Portrait by – John de Critz

Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles 1, the second Stuart king of England (1625-1649)

Henrietta Maria as a young princess of France

Ornaments worn – Double strand pearl necklace.

Pearl ear-drops.

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Henrietta Maria – 1638

Ornaments worn – Single strand pearl necklace.

Pearl ear-drops with two drop-shaped pearls in each earring.

Stomacher with spherical and drop-shaped pearls.

Shoulder band encrusted with pearls and colored stones.

Portrait by – Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Henrietta Maria by John Hoskins around 1632

Ornaments worn – Choker encrusted with colored stones and drop-shaped pearls hanging fro it at regular intervals.

Hair ornament set with pearls.

Earrings with drop-shaped pearls.

Portrait by – John Hoskins

Henrietta Maria by Anthony van Dyck in 1638

Ornaments worn – Single strand pearl necklace with a drop-shaped pearl as centerpiece.

Pearl ear-drops.

Pearl strand around the hair

King Charles I, the second Stuart king of England

Triple portrait of Charles I by Anthony van Dyck around 1636

In the above triple portrait of King Charles 1, the king can be seen wearing a single drop-shaped pearl on his left ear, in the angle showing the left side of his face, on the extreme right of the portrait. Wearing a single pearl on one ear had been a fashion during this period, and can be seen in the portraits of the kings of France, such as Francis I, Henry II, Charles IX and Henry III. King Charles I was reported to have worn this single pearl at the time he was executed by beheading on January 30, 1649.

Charles 1 as Prince of Wales

The above is a portrait of Charles 1, as Prince of Wales, executed by Isaac Oliver in 1615. Please note the single drop-shaped pearl on the left ear of the youthful prince, a hallmark of the king until the time of his death by beheading.

Catherine of Braganza – Wife of King Charles II, the third Stuart king of England (1660-1685)

Catherine of Braganza – Wife of King Charles II

Ornaments worn – Single-strand pearl necklace.

Pearl ear-drops.

Pearl hair ornament.

Several strands of black pearls on the chest.

Portrait by – Jacob Huysmans

Anne Hyde – Wife of James II, the fourth Stuart king of England (1685-1688)

Anne Hyde – Wife of King James II

Ornaments worn – Single pearl necklace consisting of large spherical pearls.

Pearl strand across the chest partially visible.

Portrait by – Unknown Artist

Queen Mary II, the fifth Stuart ruler of England (1689-1694)

King William III and Queen Mary II – Co-rulers of the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1689 to 1694

Ornaments worn by Queen Mary II – Single-strand pearl necklace.

Crown set with pearls.

Earrings with drop-shaped pearls.

Two strands of pearls hanging from shoulder brooch or clip.

King William III also wears a crown set with pearls.

Painting from the ceiling of the painted hall, by Sir James Thornhill

Photo by – James Brittain

Queen Anne, the first Queen of Great Britain and the last monarch of the House of Stuart (1702-1714)

Princess Anne at the time of her marriage in 1683

Ornaments worn – Only a pair of pearl ear drops. Simplicity in her mode of dressing appear to be the hallmark of the Queen, and in most of her portraits she doesn’t appear to wear any jeweled ornaments at all. The 1705-portrait of the Queen below, appears to confirm this observation.

1705-portrait of Queen Anne

Portrait by – Michael Dahl

1702-Portrait of Queen Anne after she ascended the throne as Queen

Ornaments worn – Even after coronation as Queen, Anne appeared to have maintained her simplicity in dressing. In the portrait above she is not wearing a pearl necklace or a pair of pearl ear-drops, as her predecessors had done before her. The only pearl ornament she appears to be wearing is a belt encrusted with a few pearls. The coronation regalia she is wearing or holding, such as the crown, the scepter and the orb, are of course studded with pearls.

The Use and Appreciation of Pearls in Europe in the Middle Ages and after will be continued in the next webpage

The use and appreciation of pearls by monarchies of other dynasties and countries of Europe in the middle ages will be considered in detail in the next webpage “The Use and Appreciation of Pearls in the Middle Ages – Page 7.”

You are welcome to discuss this post/related topics with Dr Shihaan and other experts from around the world in our FORUMS (forums.internetstones.com)

Related :-

1) History of the discovery & appreciation of Pearls- Part 1

2) History of the discovery & appreciation of Pearls- Part 2

References :-

1) Pearls Among the Ancients – Chapter 1, The Book of the Pearl – by Kunz and Stevenson.

2) Medieval and Modern History of Pearls – Chapter 2, The Book of the Pearl – by Kunz and Stevenson.

3) Byzantine Empire – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

4) Roman Empire – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

5) Holy Crown of Hungary – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

6) Goths – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

7) Ostrogoths – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

8) Visigoths – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

9) Carcassonne – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

10) Franks – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

11) Dagobert I – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

12) Charlemagne – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

13) Childebert I – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.