Origin of Name

The impressive emerald and diamond necklace was designed by Cartier London in 1937 after they had purchased a rare emerald cross of 45 carats from Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain, after the Spanish royal family went into exile in Europe in 1931, and subsequently Queen Victoria Eugenie and King Alfonso XIII separated, the Queen taking up temporary residence in the UK and later settling down permanently in Lausanne, Switzerland. The emerald cross carved from one single emerald crystal and named the “Andean Cross”is believed to have belonged to Queen Isabel II of Spain and later Empress Eugenie of France, the Spanish-born empress-consort of Napoleon III of France, Queen Victoria Eugenie’s godmother, from whom she inherited part of her name, the other part Victoria coming from her grandmother Queen Victoria.

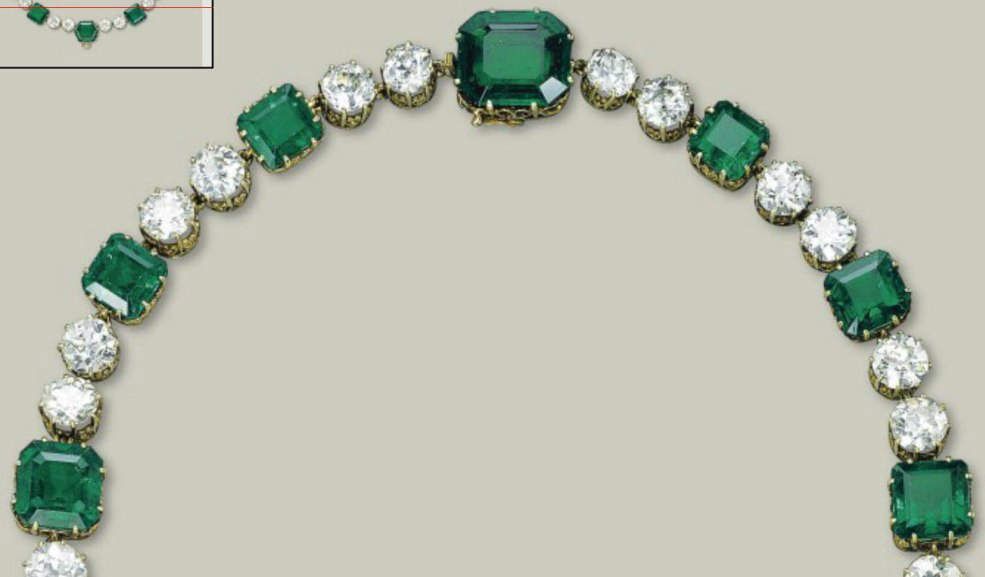

Having acquired the “Andean Cross,”Cartier decided that the extremely rare gem should be given an appropriate setting in keeping with its religious significance and royal provenance. Accordingly Cartier’s jewelry designers decided that the most appropriate setting would be for the emerald cross to be suspended as a pendant to a befitting necklace also incorporating the best of emeralds. The designers then selected over 100 carats of the best emeralds available at the time, and incorporating 12 high-quality emeralds and 24 top-quality diamonds, created the stunning emerald and diamond necklace, reflecting features of the jewelry designs of the period – Art Deco.

Simon Iturri Patiño and his wife Albina Rodriguez

Subsequently, in 1938, Simon Iturri Patiño, the Bolivian “Tin King”aka “The Andean Rockefeller”an esteemed customer of Cartier, who had previously purchased several fabulous creations of Cartier, saw the stunning necklace and the historic “Andean Cross”suspended by it, and decided to purchase it for his beloved wife, his trusted companion in his journey from rags to riches.

Magnificent Emerald and Diamond Necklace designed by Cartier

Characteristics of the Emerald and Diamond Necklace

Design features of the necklace

The emerald and diamond necklace is composed of 12 Colombian emeralds with a total weight of 108.74 carats, and 24 white/colorless diamonds with a total weight of 59.36 carats. The circumference of the necklace is 45.0 cm.

The Upper-half of the Emerald and Diamond Necklace

11 of the emeralds are cut in the traditional octagonal shape, the special cut invented for emeralds that reduces the strain on the stones while cutting and polishing, known as the “emerald-cut,” given the brittle nature of emeralds due to presence of cracks and fissures. One emerald, the lower central large emerald carrying a loop for the suspension of the Andean Cross is a hexagonal-cut emerald. The hexagonal shape is the natural shape of emerald crystals, and hence the hexagonal-cut is another cut that minimizes strain on rough emerald crystals during cutting and polishing.

The emeralds are set in gold collets of corresponding shape and the stones held in place by claw settings. The design of the necklace is perfectly symmetrical with emeralds of similar size and shape placed symmetrically on either side of the median line of the necklace. The two largest emeralds in the necklace, the hexagonal-cut emerald and the octagonal-cut clasp emerald are placed along the median line of the necklace.

Lower section of the Emerald and Diamond Necklace

Two old European-cut circular diamonds are placed as spacers between two emeralds on the necklace. Thus there are 12 spacers in the necklace occupied by 12 pairs of (24) old European-cut circular diamonds, set in circular gold collets and the stones held in place by claw settings.

The rear large Octagonal Emerald and clasp

The Central large hexagonal emerald with a loop for the Andean Cross

Art Deco features in the necklace

The necklace designed and created in 1937 by Cartier during the Art Deco period, obviously show features characteristic of the period. Some of these Art Deco features are :-

1) The striking symmetry in the design of the necklace.

2) The use of diamonds and emeralds in the necklace, two of the precious stones popular during this period.

3) The use of geometrical shapes in the necklace, such as the circular shape for diamonds and octagonal and hexagonal shapes for the emeralds.

The original Simon Patiño’s Emerald and Diamond Necklace was designed by Cartier, but later modified by Van Cleef &Arpels who acquired the necklace and the Andean Cross

The original Simon Patiño’s Emerald and Diamond Necklace was designed by Cartier in 1937, and contains all the features described above, except for the number of emeralds and diamond spacers. The original necklace was composed of 14 emeralds and 14 pairs (28) of diamond spacers, with a circumference slightly greater than the present 45.0 cm. Van Cleef &Arpels subsequently acquired the necklace from Simon Patiño’s family, and slightly modified the necklace, retaining all design features of the original necklace, but only reducing a pair of almost identical emeralds and two pairs of diamond spacers, giving the present necklace with 12 emeralds and 12 pairs (24) of diamond spacers.

The two almost identical octagonal-cut emeralds weighing 10.01 and 9.36 carats was used by the designers of Van Cleef &Arpels to create a matching pair of dangling earrings for the necklace. Each octagonal-cut emerald and one of the original Old-European-cut circular spacer diamonds still attached to it and retained in the gold collet and prong-setting, was surmounted with a trefoil similarly set with three old-European-cut circular but slightly smaller matching diamonds, to give the dangling pair of earrings shown in the image below. Each earring has a length of 3.7 cm.

Matching pair of emerald and diamond earrings created by Van Cleef &Arpels from the original Simon Patino emerald and diamond necklace

The SimonPatiño’s Emerald and Diamond Necklace and the matching pair of earrings were sold as separate lots at the Christie’s Geneva Magnificent Jewels Sale held on November 12, 2013, the necklace bearing lot no. 214 and the earrings bearing lot no. 215

Source of the emeralds ?

A lab report issued by the Swiss Gemological Institute (SSEF) bearing no. 69531 dated August 22, 2013, stated that the 12 emeralds are of Colombian origin, 8 with indications of minor oil, 4 with no indications of clartiy modification.

An Appendix Letter also issued by the SSEF for an “Exceptional Emerald Necklace”indicated that “The described necklace is very impressive in its classic design and contains twelve natural emeralds alternating with colourless diamonds of remarkable size. The emeralds for this necklace have been carefully selected and exhibit an attractive and highly matching green colour combined with a fine purity.”

The exact Colombian mine from which the emeralds originated is not known. However, given the fact that the green color of Colombian emeralds seem to vary slightly with the source, one may make an intelligent guess on the mine of origin of the emeralds.

Well-saturated, vivid green Muzo emeralds with a slightly yellowish undertone

An extract from Ron Ringsrud article “THE COSCUEZ MINE: A Major Source of COLOMBIAN Emeralds”

Emeralds in the Simon Patiño’s emerald and diamond necklace most probably originated from the Muzo emerald mine ?

The 14 emeralds in the Simon Patiño’s emerald and diamond necklace and matching pair of earrings have a well saturated slightly yellowish-green color, clearly evident from the image of the matching pair of emerald and diamond earrings created by Van Cleef &Arpels. Hence the emeralds in the necklace most probably originated in the Muzo emerald mines. Muzo emeralds are known for their beauty, and within the trade they are known for their color and size.

The fact that 8 out of 12 emeralds in the necklace and both emeralds in the earrings show evidence of minor oil treatment, indicates the clarity of the emeralds is average, which is in keeping with the clarity of Muzo emeralds. The best emeralds in terms of clarity are the Gachala emeralds.

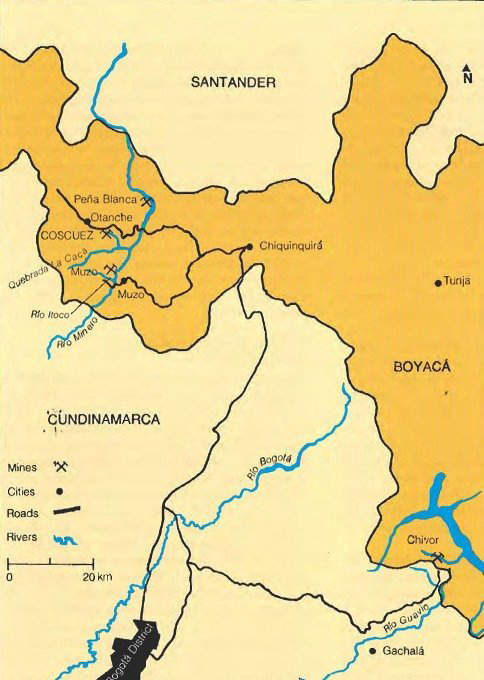

Location of the ancient mines of Muzo, Coscuez and Chivor

The ancient and historic Muzo mines is situated at the northwestern end of the NW-SE emerald belt in the branch of the Andes Mountains, known as the “Cordillera Oriental” in Boyaca Department. The other two ancient and historic emerald mines are the Coscuez mines situated about 10 kilometers north of the Muzo mines and the Chivor mines situated at the southeastern end of the emerald belt, also in the Boyaca Department. Gachala mines are also situated at the southeastern end of this belt, south of Chivor in Cundinamarca Department.

Map of Boyaca Department of Colombia, showing the emerald mining regions of Coscuez, Muzo and Chivor. Gachala in the Cundinamarca Department is also shown.

Map showing the three branches of the Colombian Andes Cordillera Occidental, Cordillera Central and Cordillera Oriental.

Discovery of the Muzo Mines by the Spanish Conquistadors in 1594 A.D.

The Spanish who had captured Chibchaland, had heard about another ancient emerald mine in Muzoland about 200 km northwest of the Chivor mines, but attempts to subdue the Muzo Indians failed, as they were a war like tribe and fiercely and successfully resisted Spanish attacks for almost 20 years, and were only partially subdued in the year 1555. Attempts made by the Spanish to locate the ancient Muzo mines proved unsuccessful due to the policy of non-co-operation adopted by the Muzo Indians. However 40 years later, in the year 1594, the Spanish on their own were able to locate the original Indian workings, closer to the present site of the Muzo mines. Production in the Muzo mines started almost immediately and the output was prolific during the first few decades, but later declined rapidly due to the cruel conditions in the mines, long working hours imposed on the workers, and compulsory labor enforced on the neighboring tribes, forcing the people to flee the immediate neighborhood of the mines. In the middle of the 17th century a disastrous fire engulfed the Muzo mines, and mining activity came to a complete standstill. The mines were abandoned and resuscitated only after Colombia gained independence from the Spanish in 1819.

Exploitation of the Muzo Emerald Mine after independence in 1819 until year 1909

After independence, the new Colombian government lacked the organization and managerial skills needed for running the mines, but realizing the potential of the mines as a revenue generator, opted for private exploitation taking 10% of the profits. Accordingly, the mines were given out on lease to private companies from 1824 to 1848, until the Congress in Bogota decreed that all emerald deposits in the country should be worked under the direction of the nation. From 1848 to 1909, the Muzo mines were worked almost continuously, but the development of the mines suffered due to lack of a sustained policy of management, technical skills, and sound geological knowledge and advice.

Exploitation of the Muzo Emerald Mine by the British-based Colombian Emerald Mining Company Ltd. from 1909 to 1913

In 1909, the Colombian Government signed a partnership contract to exploit the Muzo mines, with a British-based company, The Colombian Emerald Mining Company Ltd. controlled by South African diamond interests. The company using the knowledge, experience and technical skills gained by the exploitation of diamonds in South Africa, actively exploited the Muzo emerald deposits for a few years, but unfortunately the Government rescinded the contract and took over the sole control of the mines. Operations in the Muzo mines came to a complete standstill in January 1913, as the appropriations allocated by the Government was insufficient for re-establishing mining activity. Moreover the outbreak of World War I had a serious impact on the precious stone market that prevented the profitable exploitation of the mines.

Production at Muzo resumes after World War I

Production in the Muzo mines resumed after World War I, but the mines were again closed down in 1925, due to poor funding by the government. In 1933, the Muzo mines reopened under the direction of Peter W. Rainier, and an American group marketed production on a commission basis for the government.

In 1946, the mining rights to the Muzo mines were sold by the government to Banco de Republica, Bogota, which ran the mine profitably until the end of 1947, but subsequently incurred losses for about an year from 1948 to 1949.

Government sponsored company ECOMINAS granted authority to mine Muzo in 1968

Exploitation of the Muzo mines continued in the 1950s and 1960s, until in the year 1968 the government sponsored company ECOMINAS was granted authority to mine Muzo and also to buy stones from private parties as well as to cut and sell stones.

Muzo mines leased to the Sociedad de Mineros Boyancences for ten year periods begining from 1978

Following a period of anarchy in the Muzo mines and other government mines between 1976 and 1977, the Muzo mines were leased to the Sociedad de Mineros Boyancences for a ten year period. Since then the Muzo mines are leased by the government for 10-year periods. The Muzo mines are still under production, and the current lease is still held by the Sociedad de Mineros Boyancences. The Muzo mines were at one time the most prolific emerald mines in the world.

Muzo International, a branch of Texma Group, awarded exclusive mining rights in November 2009, and has elevated mining to global standards with full commitment to highest social, ethical and environmental standards

In November of 2009, Muzo International, a branch of Texma Group, was awarded exclusive mining rights to the Muzo mines. Shortly thereafter, the company launched a new global operation which is now mining, cutting, and polishing all newly produced Colombian emeralds from Muzo, within Colombia. Today, approximately 75% of the population of Muzo is involved in the emerald industry.

Muzo International is unique in the emerald business in that it has complete control of the value chain from mine to market. This controlled trail ensures that both the stones themselves and the methods by which they have been processed are of the highest quality, and is the foundation for the three pillars differentiating Muzo emeralds:

– Quality: Muzo International’s quality policy ensures that only non-permanent cedar oil is used to embellish the stones, whenever necessary.

– Certified Muzo origin: Unique in the gemstone industry, each Muzo International emerald is accompanied by a certificate confirming its authenticity from a highly respected independent gemological laboratory in Switzerland.

– Traceability: Each Muzo emerald is individually numbered and can be traced back to the rough it originates from.

History

A biography of Simon Iturri Patiño

Simon Iturri Patiño, “The Tin King”and “The Andean Rockefeller”

Simon Iturri Patiño, the greatest industrialist Bolivia had ever produced, from humble beginnings in early life, built up a fortune by acquiring a major part of the tin industry of Bolivia, eventually expanding his activities to other parts of the world, investing in the tin industries of Chile, England, Germany, Malaysia, Canada, Indonesia, Thailand, Nigeria and the Netherlands, and by the end of the 1930s, more than 60% of the world’s tin output was being processed at his foundries. By the 1940s he controlled the international tin market and was believed to be one of the five wealthiest men in the world. Hence he acquired the nicknames “The Tin King”and “The Andean Rockefeller.”

Simon Iturri Patino

His early life

Born in 1860 in Santiváñez (formerly Caraza), Cochabamba Department, Bolivia, Simón Itturi Patiño is the son of Eugene Itturi, his father of Spanish Basque origin and Mary, one of seven children of a well-known family of Cochabamba. He was christened Simon as he was born on the day of St. Simon, the 1st day of June every year.

After an early monotonous life as a member of a working family living in the isolated villages of this vast region, Patiño was admitted to the first year of seminary religious school at the age of eight years, after the family moved to Cochabamba. His adolescent period at school was passed in an eerie atmosphere of uncertainity, anxiety and near anarchy, as tensions between united Bolivia and Peru and neighboring Chile arose over the mineral-rich provinces of Antofagasta in Bolivia and Tarapaca, Tacna, and Arica provinces of Peru, which were exploited by Chilean enterprises, and now faced the threat of nationalization. Eventually, war broke out between Chile and United Bolivia and Peru in 1879, known as the “Saltpeter War”or the “War of the Pacific”that lasted until 1883. Bolivia was defeated at the Battle of Tacna on May26, 1880 and withdrew from the war, eventually signing a truce with Chile in 1884, after Peru was defeated and the war ended in 1883

His work with mining companies where he gains experience in the mining business

After completing his secondary education at the Seminary of Cochabamba he worked from 1882 to 1884 as a clerk in a small import business at Oruro, belonging to Cincinnatus Virreira, a Cochabamba merchant. It was at Oruro that young Patiño experienced for the first time the working of mineral mines such as Pie de Gallo, Itos and San Jose, and the pungent smells emanating from such mines.

After 1884, Patiño moved from Oruro to Huanchaca Pulacayo mining center, where he earned a modest job in the administrative section of the silver company, Compañía Hunanchaca de Bolivia. He then secured a job with the thriving German commercial firm Herman Fricke and Company, where he had on-the-job training and experience about the complicated procedures of purchasing, handling, sale and export of minerals.

His marriage to Albina Rodriguez who becomes his trusted partner in the early days of his mining venture

On May 1, 1889 Patiño married Albina, daughter of Thomas Rodriguez and Epiphany Ocampo Rodriguez. Patino was 29 and his wife 16 at the time of their marriage. The marriage turned out to be a successful one producing five children. Albina Rodriguez became Simon Patiño’s trusted companion, especially during the difficult early days of his mining venture, giving moral encouragement to her husband to continue despite all odds, staying with him in the hills, and going to the extent of selling her jewelry, to support her husband’s venture.

Simon Patiño and his family

Simon Patiño continues his work with Herman Fricke &Co. and make the acquaintance of Sergio Porto, owner of the “Salvadora”mine

Simon Patiño continued with his job at Herman Fricke &Company, and made friends with miner Sergio Porto, owner of the “Salvadora”mine, and a supplier of tin ore to their company. There are times when Sergio Porto received advances from the company against future deliveries of tin ore. There was a time when Sergio Porto ran short of funds for continued exploitation of his mine. He needed food, explosives and money to pay wages for his five workers. He approached Simon Patiño for more advances which was refused as he had not settled his previous loans.

Sergio Porto requests for financial advance from the Company to keep his mine running, but Simon Patiño makes an alternative suggestion to form a joint company which Porto accepts

Instead Simon Patiño made an alternative offer to Sergio Porto to help him out of his difficulties and keep the mine running. He suggested that both of them should form a joint company to further exploit the “Salvadora”mine. He said that he is prepared to invest 5,000 bolivianos in the company, money he had saved since he started working, to invest in a mining venture of his own. This would take care of the expenses for wages, supplies and materials. Porto was requested to go back to the mine immediately and begin work under his direct personal supervision. In return Porto would be under obligation to send a minimum of 40 hundredweights of tin ore monthly. Simon Patiño would continue working for Herman Fricke &Co. The proceeds of the sales monthly, after deducting all expenses, and setting aside a percentage for reinvestment, would be divided equally between them.

Simon Patiño said that if Sergio Porto agreed to his proposal, he would ask his Notary to prepare the partnership deed, while Porto returned to the mine immediately. Porto agreed and a legal partnership was formed to exploit the “Salvadora”in 1894.

After three years, in 1897 Simon Patiño purchases Sergio Porto’s share in the company and becomes the sole owner of “Salvadora.”

Sergio Porto became the manager of the mine. Production at the mine could not meet the target earmarked for a month. Simon Patiño while continuing to work with Herman Fricke &Co. at Oruro, sent money, food and supplies to the “Salvadora”mine. Three years passed, but “Salvadora”would not make any headway as envisaged. In frustration Sergio Porto suggested that they sell the mine, but Simon Patiño flatly refused. “You sell your part if you want, but I will not sell mine”said Simon Patiño. Eventually, Simon Patiño purchased outright Sergio Porto’s shares in the company in 1897, freeing Porto of all liabilities and assuming the debts of the company, and becoming the sole owner of “Salvadora.”

Simon Patiño resigns from Herman Fricke &Co and devotes his entire energy to develop “Salvadora”mine

Simon Patiño resigned from Herman Fricke &Co. “Salvadora”still owed money to the company, debts incurred by Sergio Porto, the previous supplier of tin ore to the company. Arthur Fricke, owner of Herman Fricke &Co. was convinced of the seriousness and honesty of Simon Patiño, the new owner of “Salvadora”and eventually Patiño’s enthusiasm and conviction won the support of Fricke, who felt that the only way to recover what “Salvadora”owed the company, was to give the necessary support to keep the mine working.

Simon Patiño moves to Salvadora mine, situated 4,000 meters above sea level. He lived in a tiny crudely built cottage, his working place as a miner. He had a servant working for him, and the Menendez foreman hired by him carried provisions by mule to the summit of Llallagua mountains.

The early period of his mining life was the most trying period of his life, but Simon Patiño was determined to continue despite all odds

This was the most trying period of Patiño’s life. He was now living at the top of a cold mountain, separated from his wife, in a makeshift cottage, facing an uncertain future. But, Patiño was determined to continue working hard and had barely anytime to relax and reflect about the future. He had only the basic equipment for mining, such as hand drills, pickaxes, hammers, and hand crushes for crushing the ore. Pieces of mineral were also handpicked and transporting the ore to the nearest railway station took 2 to 3 days. But, despite all odds, Patiño was determined to continue.

Mining suspended during the civil disturbances of the late 1890s

Besides this, the cost of operation of the mine was also rising and future prospects looked very bleak when civil disturbance broke out in the mining regions, and owners and managers of mines and trading houses sought asylum in Oruro. But, Simon Patiño remained undaunted at the top of Llallagua. His mule driver, who was also a local chief advised him to go to the safety of the city, promising to take care of the mine during his absence. In the absence of workers and disruption of supplies to the mine, Patiño was left with no choice but to agree.

Mining resumed after restoration of peace. Patiño’s young wife Albina joins her husband at the top of the summit, bringing with her money realized by selling her jewels

Peace was soon restored in the mining regions, and Simon Patiño returned to his mine, the enforced resting period having reinforced his confidence in the mining of “Salvadora.”His workers returned to the mine and exploitation continued as usual. One day his mule driver who went to Oruro to bring supplies returned to the summit with an unexpected and pleasant surprise. Patiño’s young wife Albina reached the summit on the returned journey with the mule train. Albina was worried about the solitude of her husband at the top of the summit, having understood the difficult task her husband was engaged in, at the mine. She also realized the financial difficulties her husband was facing, and sold her jewels and brought with her a few thousand bolivianos, which she gave to her husband. Simon Patiño was moved to tears by his wife’s kind gesture.

Discovery of the rich tin vein at “Salvadora”in 1900, the richest tin vein in Bolivia

Days and weeks passed with the usual daily routine at the mine. Nothing of significance transpired at the mine. One fine day in 1900, when Simon Patiño and his wife were having tea and snacks during a break, the foreman came running towards them shouting loudly, “Don Simon, come and see what we found…………. it must be pure silver. It’s a wide streak.”

Patino rushed to the tunnel followed by foreman Menendez, who carried a little lamp that lit their way. They arrived at the spot that was just blasted with dynamite where his four workers were relaxing, chewing coca. He asked his workers to go out of the tunnel and take rest, while he examined the wide streak and collected samples to be tested and analysed the following day. He left instructions with the foreman that no one should enter the tunnel until his return from Huanuni. He carried the samples to a British firm Penny &Duncan, who analysed them and gave the results to Simon Patiño, congratulating him warmly. The three samples tested showed that one contained 58% tin, the second 56% tin and the third 47% tin. It apeared that the vein of tin discovered was the richest discovered so far in the region.

Simon Patiño breaks the news of the results of the analysis of test samples confirming the richness of the tin vein, to his wife Albina, who is overjoyed by the good news

Simon Patiño returned to the mine immediately and broke the news of the find to his beloved wife, who had been close to him and supported him during his difficult days. She was overjoyed with the news of the find. Their change of fortune was not the result of chance, but the result of six years of work and sacrifice, faith and tenacity and concentration of their efforts.

Exploration of the new tin vein begins and Patiño settles in Oruro where he sets up his office, appointing a manager to run the mine and a co-ordinator to liase between the mine and the office

The operation of the mine began on a large scale as more workers were recruited for the exploitation. Business expanded rapidly and his fortunes accumulated as the prices of tin ore soared. In 1903, Simon Patiño settled in Oruro in order to take care of the company’s business and address other legal issues related to his expanding business. He appointed Alberto Nanetti as the manager and administrator of the mine and his brother Ernesto G. Quiroga as Co-ordinator between the mine and his office in the town, also addressing issues at the Llallagua mine.

The Tin King – Simon Iturri Patino

Acquiring other mines in Bolivia and the founding of the Commercial Bank of Bolivia in 1906

Simon Patiño won new concessions of land adjacent to the Llallagua mine, where further explorations were conducted. As his empire expanded he bought other mines in Bolivia, such as the Japo mine in 1905;the British-owned Uncia Mining Company in 1910;Huanuni, Kami and Canutillos mines in 1912, and later Gallofa and Colavi mines;acquired shares in the Colquechaca mine in 1919;acquired the Empresa Minera Catavi mine in 1924;the Viloco mine in 1926;the Agricultural and Mining Company of Bolivia Oploca in 1930. However, one of Simon Patiño’s first investments in Bolivia was the founding of the Commercial Bank of Bolivia in 1906 with a capital of one million sterling.

Expansion of his company to the outside world, acquiring tin smelting companies and investing in operations in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Nigeria and the Netherlands.

With the participation of British capital the “Patino Mines &Enterprises Consolidated Inc.” was registered in Delaware, United States on June 5, 1924, which allowed him to participate in mining and related activities throughout the world. This enabled him to buy one of the largest tin smelting companies in the world, Harvey Williams &Co. of England in 1929. In 1934 he gained control of Consolidated Tin Smelters Limited, formed by the merger of Harvey Williams, Cornish Tin Smelting, and Smelting and Eastern, with over 40% of global production capacity. Eventually Patiño controlled eight tin smelters spread across the world. In Bolivia Patiño gained control of 20 stanniferous operations, and eight operations in Malaysia, then the world’s largest producer of tin. Other operations were located in Indonesia, Thailand, Nigeria and the Netherlands.

Simon Patiño’s Cochabamba Palace

Simon Patiño’s accumulated fortunes make him the fifth richest man in the world and the richest in Latin America

The bulk of the wealth amassed by Patiño was between 1903 and 1929, both from his mines in Bolivia and his companies and interests located abroad. In 1925, the New York Times categorized him as one of the ten richest men on the planet. In 1940, Patiño’s fortune was estimated to be around 1,000 million dollars, considered to be the fifth richest man in the world and the richest in Latin America. In 1968, his son, Antenor stated that his fortune had reached 3,000 million dollars, while the national product of Bolivia was less than a quarter of that figure. Simon Patiño has gone down in history as the only Latin American billionaire who had the clout to enter British finance, the heart of European Capitalism until World War I. His financial clout made him the most powerful figure in Bolivia in half a century, making him an arbiter of economic life, wielding enough power either to delay the payment of taxes or bring down a government or using less drastic methods to assert his personal opinion, such as preventing the appointment of a minister.

Following a heart attack in 1924, doctors advise Simon Patiño not to return to Bolivia. He settles first in Paris, then New York and finally in Buenos Aires

Patiño had been living between Europe and Bolivia since around 1912. In 1924, following a heart attack, his doctors told him not to return to Bolivia, saying that there was no way he could live long in Bolivia, at a height of 2,500 meters above sea level. In keeping with his doctor’s advice he moved abroad permanently, first to Paris, then to New York and finally towards the end of his life, to Buenos Aires in Argentina, closer to his homeland he was so fond of and wanted so desperately to return to. While living in Paris he was appointed Minister to France and represented Bolivia in 1938 at the Evian Conference.

His death in Argentina on April 20, 1947 and his burial at Pairumani in Bolivia

Simon Patiño was now 86 years old. He was now living in a hotel suite in Argentina. He was now weak, and often spent time sitting in an armchair in his hotel suite, his beloved wife, and constant companion always by his side, taking loving care of him. Finally, at the age of 86 years, in the early hours of April 20, 1947, he passed away peacefully without any suffering. His wife, two daughters, his son Antenor and two grandchildren carried his remains to Bolivia by rail. The government declared a day of national mourning. His remains were buried in Pairumani in the presence of a large crowd. His death was reported by the press in Bolivia, Argentina, Chile and the United States under a similar title – “Death of the King of Tin.”Simon Patiño returned at last to the land he loved, the land that made him one of the richest men in the world. His wife died six year later in 1953, and was buried by the side of his grave in Pairumani.

Sale of the Simon Patiño’s magnificent emerald and diamond necklace and matching pair of emerald and diamond earrings by Christie’s at the Geneva Magnificent Jewels sale in November 2013

Simon Patiño’s Magnificent Emerald and Diamond Necklace and the matching pair of Emerald and Diamond Earrings, which was said to be the property of an important European collector, was put up for sale at the Christie’s Magnificent Jewels Sale held in Geneva on November 12, 2013. They were sold as separate lots at the auctions. The necklace was allocated lot no. 214 and the pair of earrings lot no 215.

A pre-sale estimate of US$7,183,674 – US$10,231,293 was placed on the necklace, which eventually sold within the pre-sale estimate for US$9,935,280 one of the highest achieved for such a necklace at an auction. The history, provenance and outstanding quality combined with the signatures of two of the oldest and greatest jewelry houses no doubt had a bearing on the sale price of this rare necklace from the Art Deco period.

A pre-sale estimate of US$ 413,605 – US$ 620,408 was placed on the matching pair of earrings, created from Cartier’s original necklace by Van Cleef &Arpels. The lot eventually sold for US$ 1,207,477 which was almost 3 times the lower estimate and twice the upper estimate. Here again history, provenance and the signature of the designing jewelry houses no doubt served to enhance the selling price.

You are welcome to discuss this post/related topics with Dr Shihaan and other experts from around the world in our FORUMS (forums.internetstones.com)

Related :-

1) Catherine the Great Emerald and Diamond Necklace

2) Godman Emerald and Diamond Necklace

3) Princess Faizas Art Deco Emerald and Diamond Necklace

4) Countess Alina de Romanones Emerald and Diamond Demi-Parure

External Links :-

1) https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/jewelry/a-magnificent-emerald-and-diamond-necklace-by-5738805-details.aspx2)https://www.christies.com/about/press-center/releases/pressrelease.aspx?pressreleaseid=6674

References :-

1) Bolivian Mining. Their Reality – Jorge Espinoza Morales

2) The fortunes of Simon I. Patiño – Jorge Espinoza Morales

3) War of the Pacific – From the Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

4)Simon Iturri Patiño – From the Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

5) Simon I. Patiño – Mi Llallagua- www.oocities.org/espanol/mi-llallagua/patino

6) Christie’s Press Release – The Patiño Collection to be Offered at Christie’s Geneva on November 12, 2013 – www.christies.com

7) An Important Pair of Emerald and Diamond Earrings – Sale 1400, Lot 215 – www.christies.com/LotFinder/searchresults

8) A Magnificent Emerald and Diamond Necklace, by Cartier – Sale 1400, Lot 214 – www.christies.com/LotFinder