Origin of Name

Click here to go to the Taj Mahal Diamond

The Mogul Emerald Necklace that was bequeathed to the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution in the year 2007 from the estate of Madeleine H. Murdock, is a historic and remarkable piece of jewelry that has enriched the National Gem Collection. The necklace gets its name from the carved flat emerald which is set as a pendant to the diamond necklace. The features in the emerald that point to its possible Mogul origin are :- 1) The rosette like floral motif carving, which is a characteristic Indian style of the Mogul period 2) The similarities in the carving style when compared to other carved emeralds of this period, eg. the 217.80-carat rectangular flat Mogul Emerald, engraved in the year 1695-96 A.D. 3) The emerald being cut into a flat almost hexagonal shape, equivalent to the natural shape of the stone, before the actual carving was carried out. 4) The presence of small drill holes on the sides of the emerald enabling it to be used as an attachment to a cloak or turban.

The Mogul period in India has gone down as a golden period in the history of India, renowned for its cultural, literary and artistic achievements. The greatest legacy of this period is undoubtedly the world renowned Taj Mahal, the architectural marvel built by Emperor Shah Jahaan, in memory of his beloved Queen Mumtaz Mahal, that still ranks among the seven wonders of the world. During this period the Mogul Emperors also supported and patronized all aspects of the jewelry industry, such as jewel crafting, cutting and polishing of gemstones and diamonds, and also carving and engraving of gemstones like emeralds. The carving of emeralds had achieved a high degree of precision as revealed by some of the carved emeralds of this period, but what is more surprising and puzzling to the modern day gem and diamond cutters, was how these Mogul craftsmen were able to engrave Arabic inscriptions on diamonds, which today can only be done using a fullerite pen or laser technology. Some of the famous diamonds of this period with Arabic inscriptions are the Taj Mahal Diamond, Akbar Shah-Jahangir Shah Diamond, and the Shah Diamond.

Madeline H. Murdock Mogul Emerald Necklace

©Smithsonian, Photography by Ken Larsen

Description of the emerald and the necklace

The emerald which has a dark grass-green color, characteristic of emeralds of the Muzo mines of Colombia, has a weight of approximately 100 carats. The shape of the emerald is approximately hexagonal, which is the natural shape of the crystal, but the emerald appears to have been cut deliberately as a flat gemstone with two parallel flat faces, similar to table-cut diamonds and other gemstones. Such a cut would have been the preliminary step before the master Mogul gem carvers took over and transformed the gemstone into a masterpiece in gem-carving with a rosette like floral motif with concentric circles of petals around the center of the motif. Small drill holes on the edge of the gemstone enabled it to be attached to a cloak or turban, in keeping with the royal fashions of the time. The emerald is heavily included and almost opaque, two characteristics that would have led to the gemstone being selected for carving in the first place, and not for faceting and polishing, had the stone been less included and more transparent.

Moghul emerald and diamond necklace and pendant

©Smithsonian, Photography by Ken Larsen

The emerald has been set in a gold framework as the centerpiece of a pendant surrounded by a row of 58 small, round and cushion shaped diamonds. The color contrast between the green emerald and the white diamonds is very striking. The pendant is attached to the two-row diamond necklace by a triangular attachment encrusted with 14 round-shaped diamonds. The double-row diamond necklace consists of hundreds of small rounded diamonds set on a platinum framework. The total weight of the diamonds is approximately 50 carats.

Position of the Madeleine H. Murdock Emerald in the list of inscribed/engraved emeralds of the Mogul period

In the List of inscribed/engraved emeralds of the Mogul period given below, the Madeleine H. Murdock Emerald, presently owned by the NMNH of the Smithsonian Institution, occupies the 4th place. According to this list the 350-carat Agra Emerald belonging to the Programa Royal Collections, in Madrid, Spain, is the largest engraved emerald in the world, followed by the 217.80-carat Alan Caplan’s Mogul Emerald bearing the Shia invocation in Arabic, which is at present exhibited in the Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar. The 3rd largest engraved emerald is the 142.20-carat Agha Khan III emerald, that is engraved with text from the Holy Qur’an, but whose present whereabouts are unknown.

A list of inscribed/engraved emeralds of the Mogul period

| S/N | Name of Emerald | Previous Owner | Weight of the Emerald | Type of Inscription/Carving | Present Owner |

| 1 | Agra Emerald | Unknown | 350 carats | Floral Motif | Programa Royal Collections, Madrid, Spain |

| 2 | Mogul Emerald | Alan Caplan | 217.80 carats | Shia invocation in Arabic and floral motif | Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar |

| 3 | Agha Khan III Emerald | Agha Khan III | 142.20 carats | Text from the Holy Qur’an | Unknown |

| 4 | Madeleine H Murdock Emerald | Madeleine H. Murdock | 100.00 carats | Floral motif | NMNH. Smithsonian Institution |

| 5 | Al-Sabah Emerald-1 | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait | 85.60 carats | Text from the Holy Qur’an | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait |

| 6 | Agha Khan III Emerald | Agha Khan III | 76.00 carats | Text from the Holy Qur’an | Unknown |

| 7 | Al-Sabah Emerald-2 | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait | 73.20 carats | Text from the Holy Qur’an | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait |

| 8 | Kite-shaped Mogul Emerald | Unknown | 64.99 carat | Floral Motif | Unknown |

| 9 | Al-Sabah Emerald-3 | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait | 59.60 carats | Name of Nadir Shah, and the year 1153 A.H. in Arabic | Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait |

Agra Emerald – Programa Royal Collection

© Programa Royal Collections. Agrupación Europea de Interés Económico 2006

Mughal Emerald inscribed with Shiite Invocation

© Christie’s

Floral Pattern on the Reverse Side of the Mughal Emerald

© Christie’s

Unknown 64.99-carat kite-shaped engraved emerald of the Mughal period

The chemical composition and structure of emeralds

Emeralds are beryls, that belong to the sub-class cyclosilicates, under the main class of minerals silicates, the most abundant class of minerals on the surface of the earth. In cyclosilicates six tetrahedral silicate ions (SiO4)² ¯ are linked together forming a hexagonal ring [(SiO 3 ) 6 ]² ¯ , the basic unit that is repeated, eventually forming hexagonal shaped crystals. The negative charges on the rings are balanced by the positive charges on 2 aluminum ions (Al3+) and 3 beryllium ions (Be2+), giving the formula Be 3 Al 2 (SiO 3 ) 6, known as Beryllium Aluminum Silicate. The presence of trace quantities of chromium and/or vanadium, whose atoms replace some of the aluminum atoms in the crystal structure, imparts the green color to the emeralds. When chromium atoms predominate the color is dark herbal green (eg. most of the Colombian emeralds), but when vanadium atoms predominate the color is bluish-green (eg. Zambian emeralds).

The 4 Cs of Emeralds

Like diamonds the quality of the emeralds is also based on the 4Cs, Color, Clarity, Cut and Carat weight. The top colors in emeralds are the deep vivid-green, the slightly bluish-green and slightly yellowish-green colors, all favorable colors coming out of the mines of Colombia. But, recently the vanadium-based, deep bluish-green colors of emeralds produced in Zambia, have also gained international acceptability, mainly due to their almost inclusion-free status. Clarity of emeralds are tied to the presence of inclusions. The presence of inclusions, known as “Jardin” is a characteristic feature of most emeralds, and include cracks and fissures besides actual three-phase inclusions of solids, liquids and gases. Thus their presence in acceptable quantities and treatment to hide their presence is generally accepted in the international gem trade, as finding an emerald without any inclusions is indeed a very rare occurrence. But, this conventional position regarding inclusions in emeralds is being challenged, by the production of increasing quantities of vanadium-based emeralds in some African countries like Zambia, of exceptional bluish-green color and almost free of any inclusions. Traditional emeralds which are hard and somewhat brittle, can be cut only as rectangular or square shaped step-cut stones with beveled corners, a cut developed specially for emeralds in order to reduce the mechanical strain on the gemstone during the cutting process. However, vanadium-based emeralds from certain African countries are hard and tough and could be cut in a variety of shapes besides the emerald-cut, such as cushion, pear, round, heart etc.

Characteristics of emeralds used for carving and engraving

Emeralds that are heavily included and opaque may not have gem-value, but still have good color, and might be suitable for carving and engraving such as the Madeleine H. Murdock’s Mogul emerald, and all other engraved emeralds in the above list. These emeralds in spite of their low quality have an enormous value due mainly to their antiquity and historical provenance. The 217.80-carat Alan Caplan’s Mogul emerald fetched a record price of 2.2 million dollars at a Christie’s auction held in New York in the year 2001.

History of the Madeleine H. Murdock’s Mogul Emerald

The emerald was engraved possibly during the classic period of the Mogul Empire, between 1556 and 1707

As pointed out earlier the Mogul provenance of the emerald are fairly well established, but there is no evidence to pinpoint exactly to which Mogul emperor’s period the emerald belonged to. The Mogul period in India extends from 1526, the year Delhi and Agra was captured by the first Mogul Emperor Zahir-ud-deen Muhammad who was also known as Babur, to the year 1857, when the last Emperor Bahadur Shah II, was imprisoned and exiled by the British, after the Indian rebellion of 1857. However, the most significant period of the empire, known as the classic period, extends from the year 1556, the year of accession of Emperor Jalal-ud-deen Muhammad Akbar, also known as Akbar the Great, to the year 1707, the year of death of the last great Mogul Emperor Aurangzeb. Four great Mogul emperors ruled during the classic period, and their domain included the entire Indian subcontinent and also parts of Afghanistan, with a population estimated to be around 110 to 130 million, around that time. These emperors were Akbar the Great (1556-1605), Nur-ud-deen Salim Jahangir (1605-1627), Shihab-ud-deen Muhammad Shah Jahan (1628-1658), Muhi-ud-deen Muhammed Aurangzeb (1658-1707).

Mughal Padishah Akbar the Great (1556-1605) – Portrait by Manohar, Artist of the Mughal school

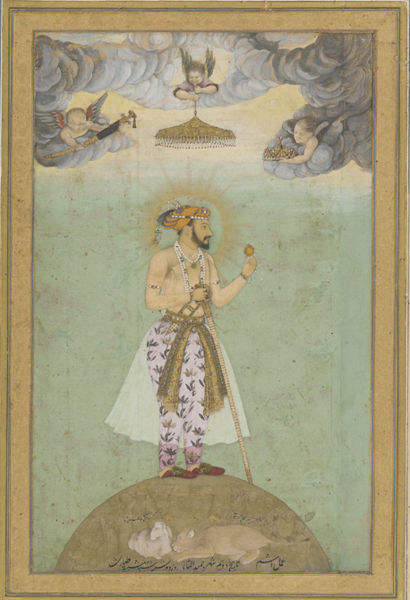

Portrait of Shah Jahangir (1605-1627) by Abu’l Hassan in 1617

Most of the significant monuments of the Mogul empire, the most visible legacies of the empire, such as the Taj Mahal, date back to this great period. The cultural, literary, artistic, and architectural achievements of this period are unparalleled in the history of the subcontinent, and the empire perhaps was the richest kingdom in the world, during this period. The courts of the Mogul emperors of the classic period reached extravagant levels of pomp and pageantry, with the mighty emperors wearing fabulous clothing, bedecked with the most exquisitely crafted gem-studded jewelry, and presiding over from splendorous jewel studded thrones. The emperor Shah Jahan is reputed to have carried this extravagance to the extreme when he ordered that all precious stones in his treasury such as diamonds, emeralds, pearls, rubies and sapphires be used for the design and construction of the most splendorous jewel-studded throne ever made in any kingdom in the history of mankind. Shah Jahan’s line of thinking seemed to be that jewels stacked in the treasury for safe keeping would not serve any purpose, and would be better utilized if studded on the throne of the monarch so that he would shine with increased brilliance in the presence of his subjects.

Emperor Shah Jahan

Emperor Aurangzeb holding court seated on a golden throne.Shaista Khan stands behind prince Muhammad Azam. The Emperor is holding a hawk with his right hand.

The turban worn by the Mogul emperors was also bedecked with jewelry, such as gem-studded aigrettes, sarpechs, and other ornaments. The Shah Jahan table-cut diamond for example was believed to be one of the valuable pink diamonds that was once worn by Shah Jahan as a turban ornament as indicated by the drill holes on the sides. Likewise, the Madeleine H. Murdock’s Mogul emerald with its drill holes on the sides could possibly have been used as turban ornament either by an emperor or a dignitary of his court during this period.

Was Colombia the source of the emerald ?

The extravagance displayed at the Mogul courts was no doubt an indicator of the vast amount of wealth concentrated in the empire, and the Spanish colonialists who controlled the emeralds mines of Colombia during this period were well aware of this. Thus it might not be surprising why the Spanish preferred to send a significant quantity of the annual production of emeralds from the mines of Colombia to the courts of the Mogul empire rather than the courts of European monarchies, as this was where the wealth of the world seem to be concentrated at that time. The Spanish received gold and silver bullion in exchange for the emeralds from the Mogul empire, which was indeed “hard currency” for the Spanish government. Enormous quantities of emeralds from Colombia, thus ended up in the Mogul empire, where they were cut and polished or engraved and set in jewelry by Indian craftsmen, for the Emperor and members of the royal household, the noble classes and other rich families. The emperors extended their patronage to the jewelry crafting industry, and several townships sprung up in the empire, such as the city of Jaipur, where the craftsmen settled and engaged in their trade.

Modern oxygen isotope analysis techniques are available for verifying the country and mine of origin of emeralds. It would have been very interesting if the Smithsonian Institution carried out such an analysis on the Madeleine H. Murdock emerald to verify the actual country of origin and perhaps the mine of origin of the emerald. Researches have prepared a table of O18/O16 ratios of 62 emerald deposits from 19 countries around the world. After finding the O18/O16 ratio of the Madeleine H. Murdock emerald using Gaston Giuliani’s technique, the value obtained is compared with the reference table, which would pinpoint the exact mine and country of origin of the emerald. Such a study would confirm the country of origin of the emerald as Colombia. But, studies carried out on four emeralds from the treasury of the Nizam’s of Hyderabad (1724-1948) using this technique had shown that three of these emeralds actually originated from Colombia, but the 4th emerald originated from a deposit in Afghanistan. Thus, it was quite possible that some of the emeralds in the Mogul treasury could possibly have originated from Afghanistan.

Possible routes by which the Colombian emeralds reached India

Emeralds mined from the historic Muzo, Somondoco and Cosquez mines of Colombia were eventually loaded on to the Galleons of the Spanish Atlantic fleet from the port city of Cartagena. The fleet then called at the port city of Portebello on the Atlantic coast of Panama, where gold and silver from Peru – that had reached the city from Panama City on the west coast by mule train, after off loading from the Spanish Pacific fleet that operated on the west coast between Peru and Panama City – were loaded. Galleons of the Atlantic fleet then sailed to Havana in Cuba, where they joined ships coming from the Port City of Vera Cruz, in the Gulf coast of Mexico, carrying gold and silver from Mexico, and silk and porcelain from China, that was brought to Mexico by the Pacific fleet from China, via the Philippines. The combined Atlantic fleet then sailed through the straits of Florida, and across the Atlantic to Spain, before the onset of the hurricane season in the Caribbean.

After the emeralds reached Spain, and the Royal family of Spain had taken their share of the emeralds, the remainder was exported to countries in Europe, and the three Islamic monarchies of the Middle East and India, the Ottoman Empire, the Persian Empire and the Mogul Empire. Emeralds bound for the Mogul Empire in India, would have been carried by vessels around the Cape and across the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea to ports on the west coast of the Indian sub-continent. Another possible route for the emeralds would have been across the Pacific from the port city of Acapulco in Mexico, by the Pacific Fleet which reached China and later the east coast India via the Philippines.

The journey of the Mogul emerald from India to the west

There are two possible ways in which jewels and jewelry from the Mughal treasury eventually ended up in the capital cities of the West. One was after the capture of Delhi and Agra by the Iranian conqueror Nadir Shah in 1739, whose forces sacked Delhi and Agra, and eventually carried away an enormous booty, that included most of the crown jewels of the Mughal empire, including some famous diamonds, like the Koh-i-Noor, Darya-i-Noor, Nur-ul-Ain, and also the renowned Peacock throne of Shah Jahan. When Nadir Shah was assassinated by his own bodyguards in 1749, most of the jewels in the Iranian treasury were stolen by his commanders and close associates. The Peacock throne was dismantled and the encrusted jewels stolen. It was possible that the Mughal emerald, like the Akbar-Shah diamond also fell into unauthorised hands and eventually found their way out of the country. Jewels that fell into the hands of ordinary soldiers of Nadir’s Afghan bodyguard were never recovered, and eventually appeared in the capital of western nations, through Istanbul, in Turkey.

Portrait of Nader Shah from the collection of the Victoria-Albert Museum

The second possible way in which jewels and jewelry from the Mughal treasury found their way in large quantities from India to London and other capitals of European nations, was after the decline and fall of the Mughal empire in the mid 19th century and the British Raj gaining ascendancy. After the suppression of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, now celebrated as India’s First War of Independence, the City of Delhi, which was under the rule of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Zafar Shah II, who was proclaimed the Emperor of the whole of India by the rebels, was captured by the British. Bahadur Zafar Shah II was arrested, tried for treason and exiled to Rangoon. The British troops who entered the city, went on the rampage killing most of the civilians hiding in their houses, and looting the entire Mughal treasury. Most of the valuable jewels and jewelry in the treasury fell into the hands of rampaging British soldiers. Most of the looted jewelry eventually ended up in London and other capital cities of Europe.The Mughal emerald, like the Agra diamond, might have been part of this loot, and appears to have reached Paris, the capital of France, one of the international centers of the gem and jewelry trade. According to a hallmark on the Mogul emerald necklace, it appears that the engraved emerald was set into the pendant and necklace by a jewelry firm in France, either during the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century.

Bahadur Zafar Shah II – Last Mughal Emperor of India

It is not known exactly when Mrs. Madeleine H. Murdock of New Jersey came into the possession of the emerald necklace. It appears that the necklace had remained in her family for a considerable period of time. Madeleine H. Murdock died on March 3, 2006, and the emerald necklace was bequeathed from her estate to the NMNH of the Smithsonian Institution in the year 2007, according to her last will.

You are welcome to discuss this post/related topics with Dr Shihaan and other experts from around the world in our FORUMS (forums.internetstones.com)

Back to Famous Diamonds,Gemstones and Pearls

Related :-

2) Emeralds of the Programa Royal Collections

References :-

1.New Acquisitions – Mogul Emerald Necklace – Department of Mineral Sciences, Website of the Smithsonian Institution

2.The Mughal Empire – From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.