History of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery from 7th-century A.D. to modern times.

This webpage is a continuation of the History of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery after the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th-century A.D. to modern times

This webpage is a continuation of the previous webpage, “History of the Discovery and Appreciation of Pearls – the Organic Gem Perfected by Nature – Page 1 – dedicated mainly to the history of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery from pre-historic times dating back to around 6,000 years to around the 6-7th-century A.D., the period in which the world’s largest bejeweled carpet incorporating Persian Gulf pearls, known as the “Winter Carpet” was produced by Khusrau II, the Sassanian king of Persia, who ruled from his Imperial Palace at Ctesiphon, from 590-628 A.D. Archeological evidence in the form of cuneiform inscriptions from Nineveh in ancient Assyria, writings of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, geographers and travelers, such as Theophrastus (371-287 B.C.), Megasthenes (350-290 B.C.), Androsthenes (300-400 B.C.), Nearchus (360-300 B.C.), Pliny (23-79 A.D.), Isidore of Charax (1st-century A.D.), Ptolemy (90-168 A.D.), and the unknown Alexandrian Greek author (1st-century A.D.) of the “Periplus of the Erythrian Sea,” were considered in detail, authenticating the antiquity of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery. The use and appreciation of pearls by ancient Egyptians, a civilization that originated in the Nile valley, closer to another ancient source of pearls, the Red Sea, was also considered, and it was shown, that such use and appreciation spread to Egypt only after the Persian conquest of Egypt in 525 B.C. After the conquest and rule of Egypt by the Greeks from 332 to 30 B.C. and later the Romans from 30 B.C. to 4th-century A.D. the use and appreciation of pearls acquired a new dimension, spreading to the western nations, who attached a premium value to these rare creations of nature, which were considered more valuable than gold and precious stones. The Greeks and Romans went all out to acquire the valuable pearls, sending their ships to the sources of pearls, such as the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar. The demand for pearls and their value saw a phenomenal increase, benefiting the countries situated around the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar. The Webpage ended with an assessment of the Persian Gulf region, as the most probable region where pearls came to be first discovered and appreciated. This webpage is a continuation of the history of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery, from the time of the Islamic conquest of the Persian Gulf in the 7th-century A.D. to modern times.

Status of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in pre-Islamic Persia and Arabia

Evidence for the prolific nature of the pearl banks of the Persian Gulf around the beginning of the Christian era

Reference was made in the previous webpage to the military campaigns of Pompey, the commander of the Roman armies in the east, who in 64-63 B.C. attacked and captured the wealthy kingdom of Pontus, the last remnant of the Selucid empire of Persia, ruled by Mithridates VI. Pompey’s armies in this campaign took large quantities of spoils-of-war, that were later taken in procession during his triumphal entry into Rome. Among the treasures of Pontus taken in procession, were 33 crowns encrusted with pearls, a grotto or shrine dedicated to the muses and decorated with pearls, and a large portrait of Pompey himself rendered in pearls. It is believed that the enormous quantities of pearls taken by Pompey in his campaigns in the East, originated undoubtedly in the Persian Gulf, the most prolific source of pearls in the region at that time. This provides indirect evidence for the prolific nature of the pearl banks in the Persian Gulf and the exploitation of these banks in the first century B.C.

Persian Gulf from outer space

Map of Persian Gulf

Large scale pearling activities first took place during the Sassanid period, that led to the development of Persian Gulf towns associated with the pearl trade, such as Rishahr on the Bushehr peninsula

The Selucid empire of Iran founded by Selucus I, after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. lasted until 247 B.C. when it was overthrown by the Parthian empire founded by Arsaces, that ruled for four centuries until 224 A.D. In 224 A.D. Ardashir I defeated the last king of the Parthians, Artabanus V, and founded the dynasty known as the Sassanid dynasty that ruled Iran for the next four centuries, until the Islamic invasion of 640 A.D. It is believed that large scale pearling activities first took place during the Sassanid period, giving a boost to the economy by generating capital, that encouraged the growth of trade and commerce in general. The growth of the pearling industry during the Sassanid period led to the development of several Persian Gulf towns, which became centers of long distance maritime trade. One such town was Rishahr on the Bushehr peninsula, that became the leading port city and center of the pearl trade in the Persian Gulf, during the Sassanid period, where excellent pearls were found and could be purchased. Another important market for pearls originating from Bahrain, that became famous during the Sassanid period, was the town of Ubulla, near Basra, that is identified by historians with the port of Vanishtabadh Ardashir, that flourished until the 13th-century A.D.

Pearls adorned the thrones, crowns, diadems and other royal paraphernalia of the Sassanid emperors like Khusrau I and Khusrau II

Pearls were an important component in the jewelry of Persia at that time. Pearls adorned not only the jewelry of the Sassanid emperors, but also their thrones and other royal paraphernalia. According to Faustus of Byzantium, in the 4th-century A.D. the Sassanid emperor’s sword belt was set with pearls. Again Ammianus Marcellinus reported that in the Roman campaign against the Sassanian king, probably Bahram V, from 420 to 422 A.D. in response to the ruthless persecution of Persian Christians, in which the Sassanian king was successfully defeated, a Roman soldier discovered a leather jewel-case full of pearls in a deserted Persian camp. Procopius Caesarensis in his book “History of the Persian Wars” written in the 5th-6th century A.D. reports that the Persian king Firuz, who fell in a battle against the barbaric Hephthalites in 483 A.D. was wearing a famously large pearl when he was killed. According to the “Chronicle of Se’ert” Khusrau I, the most powerful of the Sassanid kings, who extended his territory up to the Black Sea and the Caucasus, after two wars with the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, sent the Nestorian Bishop Ezekiel with divers to fish for pearl oysters in the Persian Gulf, suggesting some form of official involvement in the pearl fishery. During this period, it was reported that the Emperor of Persia adorned his throne with pearls, and according to the historian Sebeos, the carriage of Khusrau I was also set with pearls. The extensive use of pearls in royal crowns and diadems in Persia, was again reported during the rule of Khusrau II, the grandson of Khusrau I, who ruled between 590 to 628 A.D. Khusrau II was reported to have commissioned a crown set with pearls, after he ascended the throne in 590 A.D. Sebeos reported that Khusrau II was given a diadem and stockings set with pearls. Al-Tabari reported in the period 9-10th-century A.D. that the pearls in Khusrau II’s diadem were as of the size of eggs, and his tunic and weapons were also set with pearls.

Reference to pearling in the Persian Gulf, by pre-Islamic Arab poets

Two renowned pre-Islamic Arab poets, Al-Musaib bin Adas and Al-Mukhabbal bin al-Sa’di, in their compositions refer to the age-old profession of pearl-diving in the Persian Gulf, and the numerous hazards faced by the pearl divers. Al-Musaib bin Adas also reported the use of oil by divers to improve visibility. Few drops of oil were apparently poured into the divers eyes before he took the plunge. He also reported about a diver being attacked by a man-eating shark. Al-Baladhuri also reported that during the Arab conquest of Persia, at Nihavand, the Sassanid booty included two chests of pearls. The famous “Winter Carpet” of Khusrau II at the Imperial Palace of Ctesiphon, was also dismantled and taken as booty during the conquest of Persia.

Pearling in the Persian Gulf during the early Islamic period

In the early Islamic period Siraf became the leading port and market for pearls in the Persian Gulf, a position previously held by Rishahr during the Sassanid period

Pearling in the Persian Gulf continued in the Islamic period, and as pointed out in the previous webpage there are six references to pearls in the Holy Qur’an, the sacred text of Islam revealed to Prophet Muhammad by God almighty through the medium of archangel Jibreel (Gabriel). During the early Islamic period, “Siraf,” still on the Persian side of the Gulf, became the leading port and principal market for pearls, in the Persian Gulf, a position that was previously held by Rishahr on the Busheshr peninsula, also on the Persian side of the Gulf, during the Sassanid period.

Disruptions to the pearl fishery on the Arabian side of the Gulf in the mid-8th century and late 9th and 10th centuries

After the death of Ali ibn Abu Talib in 661 A.D., the 4th and the last rightly guided caliphs, political control of the Islamic empire passed to the Umayyad dynasty founded by Abu Sufyan, with its capital in Damascus, Syria. The Umayyad caliphate was overthrown in 750 A.D. by the Abbasids who shifted the capital to Baghdad in Iraq. The Abbasid caliphate fell in 1258 after the Mongol invasion. The pearl fisheries on the Arabian side of the Gulf was partly disrupted due to political instability during the transition period from Umayyad rule to Abbasid rule, in the mid-8th century A.D. Again during the late 9th and 10th centuries, the Abbasid state lost control of eastern Arabia to the Zanj rebels followed by the Qarmathians, resulting in some disruption to the pearl fishery on the Arabian side of the Gulf. The Qarmathians are said to have taxed Bahrain’s pearl trade highly during this period, and also the trade in the nearby mainland port of Al-Uqair.

Interesting account of pearl-fishing in the Persian Gulf is given by the 10th-century Arab traveler, historian and geographer al-Masudi in his book on world history and geography “Muruj adh-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jawhar” (The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems)

Ali bin al-Hussain al Masudi (896-956 A.D.), the renowned early Arab traveler, historian and geographer of the Abbasid period, known as the “Herodotus of the Arabs,” was one of the first to combine history and scientific geography in one of his famous works, known as “Muruj adh-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jawhar” – The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems. Al-Masudi traveled most of his life beginning in 915 A.D. when he was just 19 years old. He traveled widely through Arabia, Syria, Egypt, Persia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and other regions of the Caspian Sea, the Indus valley and other parts of India and China. He also sailed in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas. Sailing through the Indian Ocean he reached ports on the east-African coast, the west coast of India and Sri Lanka. He spent his last years in Syria and Egypt where he wrote his famous works. He is believed to have written over 20 books, but his major work written in 30 volumes was known as Akhbar-az-zaman (The History of Time), an encyclopedic work including political history, and other branches of human knowledge and activities, followed by Kitab-al-awsa (Book of the Middle) a supplement to Akhbar-az-zaman. The two works did not have much impact possibly because of their extraordinary length. So he rewrote the two works combining them into a single abridged edition, known as “Muruj adh-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jawhar” (The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems), that was completed in 947 and revised just before his death in 956. The combined book became very famous, and established Masudi’s reputation as a leading historian towards the end of the first millennium.

The book consists of 132 chapters and two halves of which the second half was a history of Islam, beginning with the Prophet Muhammad and dealing with the Caliphs, the four rightly guided caliphs immediately after the prophet, The Ummayad Caliphs and the Abbasid Caliphs up to his own time. The first-half of the Muruj adh-dhahab was enormous dealing with the history of the world, beginning with the creation of the world, Jewish history and the history of ancient civilizations, followed by chapters describing the history, geography, social life and religious customs of both Islamic and non-Islamic lands, such as Greece, Rome, India etc., including accounts of the oceans, the climate, the solar system, the calendars of various nations, great temples etc. Some of the sections of interest in his account include those on pearl diving in the Persian Gulf, amber found in east Africa, burial customs of India, the land route to China, and navigation in general, with its hazards such as storms and water spouts. According to al-Masudi pearl-fishing in the Gulf begins in April and continues for six months until September. He mentions the waters around Bahrain and Qatar as areas rich in pearls.

Pearling in the Persian Gulf from the 11th-century until the arrival of the Portuguese in the early 16th-century

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni in his book “Kitab al-Jawahir” refer to the pearl fishery of the Persian GUlf

One of the first references to pearling in the Gulf comes in the 11th-century by Nasir-i-Khusrau in his book the “Safarnama.” According to him the Sultan of al-Hasa collected only half the pearls of that collected by the divers of Bahrain, on the opposite side of el-Qatif in eastern Saudi Arabia. This is a comparison of the harvest of pearls taken around the island of Bahrain with that of el-Qatif on the opposite side of it, and confirms the fact that the pearl banks around the Bahrain island was the most lucrative in the Persian Gulf. Another reference to pearling in the Gulf in the 11th-century, comes from Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, the renowned scientist, mathematician, geographer, historian and traveler, in his book “Kitab al-Jawahir” (The Book of Precious Stones), that was considered the most complete book on mineralogy in his time, describing various minerals and cataloguing them by color, odor, hardness and density. A section on pearls in this book, gives Persian Gulf as a source, and indicates the location and depth of the pearl banks. Details are given on the timing of pearl fishing and the mode of opening oysters, that were left overnight after harvesting.

Reference to the pearl fishery of the Persian Gulf, by the Spanish Jewish Rabbi, Benjamin Tudela, who traveled across the known world at that time from 1160-1173

The next reference to the pearl fishery of the Persian Gulf comes from the Spanish Jewish Rabbi, Benjamin of Tudela, the medieval traveler who visited Europe, Asia and Africa in the 12th-century. His travels included voyages by sea as well as overland journeys, and was probably undertaken with the intention of visiting Jewish holy lands and meeting Jewish communities scattered across the globe. He began his journey around 1160 from northeast Spain traveling northwards to France, and reaching Marseilles embarked on a ship that took him along the northern coast of the Mediterranean, visiting cities like Genoa, Pisa, Rome, various towns in Greece, Anatolia and Constantinople. Leaving Constantinople he sailed along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean visiting the port cities of Gallipoli, Kilia and the islands of Samos, Rhodes and Cyprus. Then on the mainland he visited Antioch, Tripoli, Beirut, Sidon, and lands in present day Israel, such as Jaffa, Samaria, Nablous, and the Holy City of Jerusalem. After visiting all sacred places associated with Judaism in Jerusalem, he went to Bethlehem and Hebron. Then through Jordan he visited Damascus in Syria. From Damascus, through Baalbec, Hamah, he reached the ruined city of Nineveh near Mosul in northern Iraq.

Benjamin of Tudela

While sailing through the Persian Gulf Benjamin of Tudela observes at first hand pearl fishing activities taking place around the island of Bahrain and the waters of El-Qatif

Then moving downwards along the banks of the Eupharates, he reached Baghdad, the capital city of the Abbasid caliphate. He pays a glowing tribute to the Abbasid Caliph at that time for his just treatment of all his subjects including the Jews, who were granted a special hospital, describing him as a model sovereign in all respects. From Baghdad he reached the ruined city of Babylon and eventually Basra on the Tigris, at one end of the Persian Gulf. From Basra he entered Persia, visiting the towns of Kuzestan, Hamadan, Isfahan, and Shiraz, and then appeared to have returned to Kuzestan on the Tigris. From Kusestan he boarded a vessel, traversing the Persian Gulf and reaching El-Qatif, a pearling town on the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf, opposite the Island of Bahrain, the main center of pearling in the Gulf. Then from El-Qatif he appears to have taken a vessel that sailed through the remaining part of the Persian Gulf, and passing through the Strait of Hormuz entered the Gulf of Oman, and sailing across the Indian Ocean reached Quilon on the Malabar coast, and then the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). It was while sailing through the Persian Gulf that he observed at first hand the pearl fishing activities around the island of Bahrain and the waters of El-Qatif.

Benjamin of Tudela’s work, “The Travels of Benjamin” is considered as an important work on the status of the Jewish community in the 12th-century and also the geography and ethnography of the middle ages

It is not certain whether he sailed round the island of Ceylon on his way to China across the Bay of Bengal. On his return journey from south Asia, he reaches the Persian Gulf again and sailing along the coast of Oman and Yemen reach the Red Sea, which he crosses at the entrance to reach Abyssinia (Ethiopia). From Abyssinia he crosses into Egypt, where he visited the Cairo, Giza, Ain Schams, Boutig, Zefita, Damira and finally Alexandria, the port city on the Mediterranean. From Alexandria he boarded a vessel that took him across the Mediterranean landing in Messina near Rome. Before returning to Spain, he appears to have traveled northwards from Rome reaching Germany and then France before returning to Spain in 1173 A.D. He characterized the city of Paris as friendly and hospitable to the Jewish people. He described his travels and experiences in his book “Masa’ot shel Rabi Benjamin” (The Travels of Benjamin), with emphasis on the Jewish communities he visited, giving details of their populations, customs and traditions and about their community leaders. According to Benjamin Tudela’s computation the number of Jews in the lands he visited totaled 768,165. Benjamin Tudela’s work is considered by historians as trustworthy and reliable, and an important work not only on the status of the Jewish community scattered across the world at that time, but also the geography and ethnography of the middle ages.

The emergence of Julfar as a second pearling center after Bahrain in the 12th-century A.D.

Al-Idrisi, the renowned Arab geographer of the 12th-century A.D. based in Andalusia of Islamic Spain, was the foremost authority on geography of the period, and was hired by the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II to complete the geographical information obtained in his age. The king having made a ball of silver to represent the globe, requested Al-Idrisi to mark on this ball all his findings about the earth, which he did to the satisfaction of the king. Al-Idrisi is credited with the discovery of the upper sources of the Nile, and wrote the book “Trip by a Traveler Eager to Explore the Horizons,” after his travels in the 12-century A.D. Al-Idrisi in his book of travels referred to Julfar, situated north of Ras al-Khaimah, along with the island of Qays as another pearling center in the Gulf, though it did not rival Bahrain in terms of the scale of fishing. Julfar maintained its status as an important pearling center up to the time of Portuguese control in the 16th-century. Julfar was somewhere midway between the pearl banks on the Arabian side of the Gulf and Hormuz the main market for pearls during that period, a significant fact that influenced its development as an alternative pearling center to Bahrain. Al-Idrisi described the area between Bahrain and Julfar as having a great number of desert islands frequented only by birds, such as the small islands in the Abu Dhabi emirate like Sirr Bani Yas, Zirku. Qarnain, Das and Dalma etc. It appears that during the time of Al-Idrisi the pearl banks around these islands were not harvested. According to Al-Idrisi there were around 300 well-known pearl fisheries in the Persian Gulf.

Ibn Batuta on pearling in the Persian Gulf in the early 14th-century (1328-1332 A.D.)

Reference to pearling in the Persian Gulf in the 14th-century comes from Ibn Batuta the renowned Moroccan traveler whose travels lasting 30 years is given in his book the “Rihla,” “the Journey,” written in 1354-55

Reference to pearling in the Persian Gulf in the 14th-century comes from none other than one of the greatest travelers ever in the history of mankind, Hajji Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, the renowned Moroccan Berber, Islamic scholar and traveler, who is reputed to have traveled a distance of 120,000 km. (75,000 miles) within a period of approximately 30 years, beginning from 1325 A.D., stretching from Fez in Morocco to Beijing in China, traveling across 40 countries, meeting 60 heads-of-state, serving as advisor to at least two dozen of them and performing four Hajj pilgrimages. He began traveling at the age of 21 and completed his travels at 51, in the year 1354 A.D. At the instance of the Sultan of Morocco, Abu Inan Faris, Ibn Batuta dictated an account of his journeys to Ibn Juzayy, a scholar from Granada in Muslim Spain, who recorded it. The account recorded by Ibn Juzayy and interspersed with his own comments, was completed in 1355 A.D., and the manuscript was titled “A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling” that subsequently came to be referred popularly as the “Rihla” or “The Journey.” The “Rihla” names more than 2,000 people whom Batuta met or whose tombs he visited. His descriptions of life in some of the regions he visited such as Turkey, Central Asia, the Maldives, the Malay peninsula, parts of India, East and West Africa are a leading source of information, and in some cases the only source of information, about life in these regions in the 14th-century. Given the enormous volume of facts included in his accounts, the thousands of names of people he met and places he visited and dates, it is difficult to imagine that all this information was committed to his memory, and later dictated to the scribe. Thus, contrary to what historians believe that all information provided by him came from his memory, it is highly probable that Batuta made some form of notes during the 30 years of his travels, that was subsequently used in providing the accurate information contained in a major portion of the “Rihla.”

Ibn Batuta- Artistic impression

The section of Ibn Batuta’s journey that takes him sailing across the Persian Gulf, through the Gulf of Oman and the Straits of Hormuz and ending in the pearling town of Al-Hasa on the Arabian side of the Gulf. This journey takes place between his second Hajj performed in 1328 A.D. and third Hajj performed in 1332 A.D.

Ibn Batuta after performing his second Hajj in 1328 A.D., made his way to the port city of Jeddah from where he embarked on a boat sailing down to Yemen. Arriving in Yemen he visited the coastal town of Zabid, the highland town of Ta’izz, where he met the king of Yemen, Mujahid Nur al-Din Ali. He then proceeded to Aden, where he embarked on a ship sailing to Zeila, on the Somali side of the Gulf of Aden. He then sailed around the Horn of Africa, down the Somali seaboard reaching Mogadishu, the main city in Somalia, at the zenith of its prosperity, described by Batuta as an exceedingly large city with many rich merchants and famous for its high-quality fabric exported to Egypt, and ruled by a Sultan who was equally fluent in the Somali language and Arabic. He then sailed down the Swahili coast, calling at the island port cities of Mombassa, Zanzibar and finally Kilwa, the furthest he reached on the east coast of Africa. Kilwa was an important transit center in the gold trade in Africa at that time, and Batuta described its town as one of the most beautiful and well-constructed towns in the world. With the onset of the southwest monsoon, Batuta returned by ship to the Arabian Peninsula, and by way of Dhofar reached Oman. He then entered the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz, probably in the months of April/May and witnessed the pearl fishing taking place around the islands of Bahrain and the waters of Al-Qatif. According to Batuta the pearl banks found between Siraf and Bahrain was fished in April/May, by divers and traders from Bahrain, Al-Qatif and Persia. He further goes on to state that one-fifth of the harvest of pearls went to the Sultan and many divers were in debt to the traders. Ibn Batuta’s voyage across the Gulf ended in Al-Hasa, the ancient pearling town on the Arabian side of the Gulf. From al-Hasa he crossed the Arabian desert to reach Jeddah and then proceeded to Mecca to perform his third Hajj in 1332 A.D.

Reference to pearling in the Persian Gulf off the coast of Basra in the northern end of the Gulf, in the Catalan Atlas of 1375

The next reference to pearling in the Gulf comes in 1375 A.D., in the Catalan Atlas of the same year. According to this atlas pearling was conducted beyond the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, for the Baghdad market. This was a reference to the pearl fishery that existed in the northern end of the Gulf, off the coast of Basra.

According to Gonzalez de Clavijo, Hormuz appears to have taken over as the main market for pearls from the Persian Gulf at the beginning of the 15th-century, a position previously held by Baghdad

Baghdad which was the capital of the Abbasid empire from 750 A.D. to 1258 A.D. was the main pearl market in the Persian Gulf region, during this period, from where pearls reached the markets of Bombay in India and other markets in Europe. Baghdad continued to maintain this position even after the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate, until the late 14th-century according to a reference in the Catalan Atlas of the Year 1375. However, by the 15th and 16th centuries Baghdad lost its pre-eminent position as the main pearl market in the region, a place that was taken by the kingdom of Ormuz, based in the island of Ormuz (Hormuz) on the opposite side of the Gulf, in the Strait of Hormuz, closer to the Iranian mainland, just 16 km from Bandar Abbas. Gonzalez de Clavijo reported that in 1403-1406 A.D. Pearls harvested in the Gulf reached Hormuz, the center of the pearl trade in the early 15th-century, before they were exported to the western world.

Ahmed ibn Majid on the status of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery towards the end of the 15th-century

Ahmed ibn Majid reported towards the end of the 15th-century in 1490, that Bahrain’s pearling industry had reached enormous proportions, employing approximately a 1,000 vessels for fishing pearls in its waters. Thus, it appears that Bahrain’s pearl industry had grown to a considerable extent prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in the early 16th-century, that led to its disruption. Ibn Majid also recorded that around Bahrain there were a number of islands, some inhabited and other uninhabited, where pearl fisheries were held. The uninhabited islands were visited by pearl-fishers only during the pearling season.

The Portuguese explorer Lodovico Barthema visited the Persian Gulf in 1508 and in the account of his travels gives a description of the method of harvesting pearl oysters

Lodovico Barthema the Portuguese explorer visited the Persian Gulf and the island of Ormus in 1508. In his account of the visit, he gives a description of how pearl harvesting was carried out in the Persian Gulf, a process, which in its main features had remained constant through out the centuries, with little modifications if any. The following is an extract from his travels relevant to pearl harvesting :-

“At three days’ journey from this island they fished the largest pearls which are found in the world; and whoever wishes to know about it, behold! There are certain fishermen who go there in small boats and cast into the water two large stones attached to ropes, one at the bow, the other at the stern of each boat to stay it in place. Then one of the fishermen hangs a sack from his neck, attaches a large stone to his feet, and descends to the bottom–about fifteen paces under water, where he remains as long as he can, searching for oysters which bear pearls, and puts as many as he finds into his sack. When he can remain no longer, he casts off the stone attached to his feet, and ascends by one of the ropes fastened to the boat. There are so many connected with the business that you will often see 300 of these little boats which come from many countries.“

The island Lodovico Barthema refers to in this extract, is the island of Hormuz. The richest pearl banks in the Persian Gulf, around the island of Bahrain was at a distance of three days journey from the island of Hormuz, at the entrance to the Gulf, which was the main market for pearls during this time. From Hormuz pearl dealers and merchants reached the main pearling centers of Bahrain and Julfar to purchase pearls, which were then brought to the island of Hormuz to be re-sold to international buyers from Europe and India.

History of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery from the time of arrival of the Portuguese in 1508 until their final eviction from the Gulf in 1650 and till the end of the 17th-century

A brief history of the Portuguese colonization of the Persian Gulf region

The Portuguese take control of the entire Arabian side of the Persian Gulf in 1521. They did not interfere directly with the pearl fisheries, but imposed heavy taxes on the boats taking part.

Shortly after the visit of Barthema in 1508, the Portuguese, under Albuquerque moved into the Persian Gulf region taking control of the island of Hormuz and the port city of Muscat. They gradually extended their control over the entire Arabian side of the Gulf, capturing Bahrain and El-Qatif in 1521. The Portuguese did not directly interfere with pearl fishing activities in the Persian Gulf, but instead using their fire power, imposed heavy taxes on the boats taking part in the fishery, requiring them to take out a license, that cost 15 abassis. They stationed a fleet of brigantines to sink any boat that refuses to comply with their orders. The Portuguese were the absolute masters of the Persian Gulf region only for 38 years, during which period they imposed their harsh tax measures. During this period it was reported that even the Persians were obliged to pay a tax on the pearl fishery to the Portuguese.

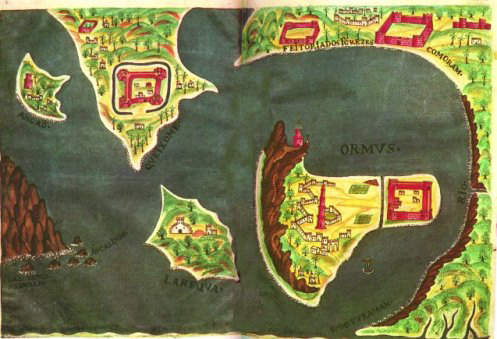

17th Century Portuguese Map of the bell-shaped island of Hormuz

Despite expulsion from Al-Qatif in 1559, the Portuguese continued to control the vital pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf until the end of the 16th-century

The first reversal of the Portuguese in the Gulf came in 1559 when they were expelled from Al-Qatif by the fighters of the Arab tribe of Bani Abd al-Qais. However, they continued to influence events in the Persian Gulf and control the vital pearl fisheries around the islands of Bahrain and other regions of the Persian Gulf, until the end of the 16th-century. Eventually they were also expelled from Bahrain by Shah Abbas I of Persia in 1602, with the help of the British. However, they still managed to hold on to Hormuz till 1622, from where they manipulated the international pearl trade. The Portuguese were expelled from Hormuz in 1622 by Shah Abbas I, but they continued to hold on to Muscat for a much longer time because of their well fortified fort.

The Portuguese were finally ousted from Muscat in 1650 by the resistance fighters of Imam Nasir bin Murshid al-Yaribi, who became the most powerful leader of the Persian Gulf during that period

It was left to the Omanis themselves to organize resistance against the Portuguese and finally oust them from Muscat on January 23, 1650. The campaign against the Portuguese was led by Imam Nasir bin Murshid al-Yaribi, who became the undisputed leader of Oman and Muscat, the first ruler of the Ya’aruba dynaty, and the most powerful leader in the Persian Gulf in the mid 17th-century. The Imam then sent his troops against the Persians who were controlling Hormuz and captured it by the end of 1650. The powerful Imams of the Ya’aruba dynasty after bringing under their control the coastal areas on the Persian side of the Gulf, went after the Portuguese in East Africa, ousting them fort by fort such as Mombasa and Zanzibar, and capturing the entire coastal region of East Africa north of Mozambique. Thus, the Imams of the Ya’aruba dynasty transformed Oman and Muscat into an empire in the Arabian peninsula, colonizing lands in Persia, east-Africa and also India.

Reference to the pearl fishery of the Persian Gulf by Duarte Barbosa, Portuguese India Officer between 1500 and 1516, traveler and writer

A brief biography of Duarte Barbosa

Duarte Barbosa reached Malabar coast in India around the year 1500, accompanying his uncle, Goncalo Gil Barbosa, who traveled in the 1500 fleet of Perdro Alvares Cabral and was left as a factor in Kochin, and later transferred to Cannanore. Duarte Barbosa learnt the local language Malayalam and in 1503, served as interpreter to Francisco de Albuquerque in his contacts with the Rajah of Cannanore. He served both as clerk and interpreter to the Portuguese colonial authorities, and returned to Portugal in 1515. After returning to Portugal he completed the manuscript of his book, titled the “Book of Duarte Barbosa” in which he described his travel experiences, one of the earliest examples of Portuguese travel literature, completed around 1516. It was after completing his book in 1516, that he joined his brother-in-law Ferdinand Magellan, on the famous journey of circumnavigating the earth, which began on August 10, 1519 from Seville, in southern Spain. Traveling across the Atlantic and the Pacific, Magellan was eventually killed on April 21, 1521, at the Battle of Mactan, in Philippines. Duarte Barbosa, who was one of the few survivors of the battle, was appointed the co-commander of the expedition along with Joao Serrao. However, just 10 days after this, Duarte Barbosa together with several of his colleagues, were poisoned and killed on May 1, 1521, at a banquet held by the Rajah of Cebu, in the Philippines, having been invited for the occasion to receive a gift for the king of Spain.

Barbosa refers to the two important centers of the pearl fishery Bahrain and Julfar, and the main market for pearls Hormuz in the region

In his book, the “Book of Duarte Barbosa” he refers to Bahrain, which has a great pearl fishery and market. He also refers to Julfar, as having another great pearl fishery, and refers to the island of Hormuz,, as a center of the pearl trade from where pearls were exported to India and other countries. According to Barbosa, Hormuzi merchants traveled to both Julfar and Bahrain to buy pearls for redistribution to India and other countries.

Hormuz Island and Bandar Abbas- Satellite Photo taken by NASA in 2003

Gasparo Balbi, the Venetian court jeweler visited the Persian Gulf in the late 16th-century

Gasparo Balbi, the Venetian court jeweler visited the Persian Gulf in 1580 A.D. to inspect its pearl markets. According to him the best pearls were those that came from Bahrain and Julfar. Balbi also provided a list of places inhabited by pearl fishers or visited by them during the pearling season. The list includes small islands in the Abu Dhabi emirate, such as Sir Bani Yas, Zirku, Qarnein, Das and Dalma, as well as coastal settlements that were to become permanently established such as Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al-Qaiwan and Ras al-Khaimah. He also noted the presence of temporary pearling encampments all along the coast. It is believed that the visit of the Venetian court jeweler in the late 16th-century might have been an attempt to forge direct links between the pearl producing areas and the western European markets, eliminating the need to obtain pearls through intermediate markets and merchants, such as the Jewish and Armenian traders from the eastern Mediterranean pearl markets of Damascus, Aleppo and Constantinople and southern Mediterranean pearl markets of Cairo and Alexandria.

Reference to the Persian Gulf pearl fishery by J.H. van Linschoten, who visited the fishery in 1596

John Huyghen van Linschoten, Secretary to the Portuguese archbishop of southern India, visited the pearl fishery of the Persian Gulf in 1596, and described what he saw as follows :-

“The principal and the best that are found in all the Oriental Countries and the right Oriental pearles, are between Ormus and Vassora in the straights, or Sinus Persicus, in the places called Bareyn (Bahrain), Catiffa, Julfar, Camaron, and other places in the said Sinus Persicus, from whence they are brought into Ormus. The king of Portingale hath also his factor in Bareyn (Bahrain), that stayeth there onlie for the fishing of pearles. There is great trafficke used with them, as well in Ormus as in Goa.

Hormuz prospered as an international market for the distribution of pearls during its occupation by the Portuguese from 1508 to 1622

Thus, it appears that the kingdom of Hormuz in spite of being subjugated by the Portuguese from 1508 to 1622, prospered by the pearl trade, and became the international market for distribution of pearls worldwide. As described by George Frederick Kunz, in his “Book of the Pearl,” Ormus became the halfway house between the East and the West, where the treasures of the Orient were gathered in abundance, making it one of the greatest emporia in the world. Ormus became renowned for its wealth and commerce, that the name Ormus became synonymous with wealth and luxury, embodied in the Arab saying, “If all the world were a golden ring, Ormus would be the jewel in it.” At the height of its popularity as an international market for pearls, Hormuz supported a population of 40,000 people.

Drawing of the old town of Hormuz by A W Stiffe, with the fort on the right and a mosque minaret to the left.

The control of Hormuz passes from the Portuguese to the Persians in 1622 and later to the Omanis in 1650

The Portuguese were ousted from Hormuz in 1622 by Shah Abbas I with the help of the British. After the Persian takeover of the island, Hormuz continued to maintain its status as an international pearl market, pearls from Bahrain, Julfar and other pearling centers in the Gulf reaching the island to be sold to international buyers. Thus, the prosperity of Hormuz continued under Persian rule. However, in 1650 soon after the Portuguese were ousted from Muscat by the fighters of Imam Nasir bin Murshid al-Yaribi, the forces of the Imam attacked and captured the island of Hormuz from the Persians. Thus, Hormuz now came under the control of the Imam of Muscat and Oman. It was around this time between 1651 and 1655, that Tavernier, the French jeweler and traveler visited Hormuz, during his 4th-voyage to India.

Hormuz Island- Persian Gulf

Portuguese Fort- Hormuz Island

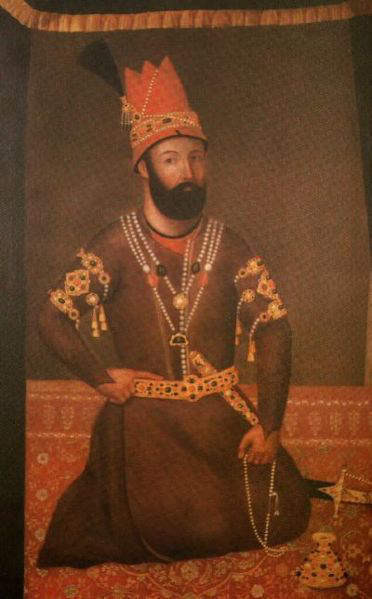

Tavernier visits Hormuz between 1651 and 1655, during his 4th-voyage to the east, where he saw the “most beautiful pearl in the world,” known as the Imam of Muscat Pearl.

At the time Tavernier visited Hormuz between 1651 and 1655, the Khan of Hormuz had hosted a party in honor of the Imam of Muscat, Sheik Nasir bin Murshid al-Yaribi, who had recently liberated his country by driving out the Portuguese from their last stronghold in the Gulf, Muscat, and had now wrested control of the Island of Hormuz from the Persians. Tavernier also had the privilege of receiving an invitation for this grand occasion. Soon after the grand entertainment ended, the Imam of Muscat, gave a surprise to the invited guests when he drew out from a small purse an exceptionally beautiful pearl, which he exhibited to the distinguished guests around him. Tavernier, who was a special guest on this occasion and was a well known jeweler and gem-merchant, was given the rare privilege of handling and examining this beautiful specimen. He referred to this pearl as “The Imam of Muscat Pearl” and described it in the following terms, “Although the pearl weighed only twelve and one sixteenth carats (forty eight and a quarter grains), and was not perfectly round, it surpassed in beauty all other pearls in the world at that time. It was so clear and lustrous as to appear translucent.”

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier- Dressed in the robes of honor presented by Shah Abbas II of Persia.

According to Tavernier, the Khan of Ormus, the chief host of the function offered 2,000 tomans ($34,500) for the pearl, but the Imam would not part with his rare and valuable treasure. As the news of this extraordinary pearl reached the mighty Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, he conveyed an offer of 40,000 escus ($45,000) for the pearl, but the Imam still refused to part with it.

In describing the fisheries around the Island of Bahrain, which had been retaken by the Persians in 1622, Tavernier wrote in 1670 :-

There is a pearl fishery round the Island of Bahren (Bahrain), in the Persian Gulf. It belongs to the King of Persia, and there is a good fortress there in Bahrain, where a garrison of 300 men is kept…When the Portuguese held Hormuz (Ormus) and Muscat, each boat which went to fish was obliged to take out a license from them, which cost fifteen abassis ($5.45), and many brigantines were maintained there in Bahrain, to sink those who were unwilling to take out licenses. But since the Arabs have retaken Muscat and the Portuguese are no longer supreme in the Gulf, everyone who fishes in Bahrain pays to the King of Persia only five abassis, whether his fishing is successful or not. The merchant in Bahrain also pays the king something small for every 1,000 oysters. The second pearl-fishery is opposite Bahren (Bahrain) on the coast of Arabia-Felix, close to the town of El Katif, which, with all the neighboring country, belongs to an Arab prince.An interesting account of the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf published in 1671 A.D. in an anonymous work titled “The History of Jewels”

In Streeter’s book “Pearls and Pearling Life” an interesting account of the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf in the late 17th-century is given in an anonymous work titled “The History of Jewels” published in 1671 A.D. The relevant extract from this anonymous work reads as follows :-“Before we speak of the manner how they fish for pearls. and of their different qualities, we must make report of the diverse places of the world where they are found.First of all they have discovered four fishing places for pearls in the East, the most considerable is performed in the isle of Bahrein, in the Persian Gulph; that which appertains to the Sophy of Persia, who receives thence a great revenue.While the Portuguese were masters of Ormuz and Mascati, every vessel which went to fish was obliged to take a passport from them at a dear rate; and they maintained always five or six small galleys in the Gulph, to sink those barks which took no passports; but at present they have no further power upon those coasts, and each fisher forfeits to the king of Persia, not above one-third of what they gave to the Portuguese.The second fishing is over against Bahrein. upon the coast of Arabia- Felix, near to the city of Catif, which belongeth to an Arabian prince who commandeth that province. The most part of the Pearls which are fished in these two places,, are carried into India, because that the Indians are not so hard, but give a better price for them than we; they are therefore carried thither, the unequal as well as the round, the yellow as well as the white, every one according to its rate : some of them also are sold at Balfora, and those which are transported into Persia and Moscovy,, are sold at Bandarcongue, two day’s journey from Ormuz. They fish twice in a year, in the months of March and April, and in the months of August and September; the depth where they fish is from four to twelve fathoms, and the deeper the oyster is found the pearls are the whiter, because the water is not so hot there, the sun not being able to penetrate so deep. Comparison of Tavernier’s account and the unknown authors account on the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf in the late 17th-century after the expulsion of the Portuguese

The account of the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf by the unknown author of “The History of jewels” published in 1671 predates the previous account written by Tavernier as appearing in his book “The Six Voyages of J. B. Tavernier” published in 1676. There are some similarities in the two accounts, on the taxation by the Portuguese when they were masters of Hormuz and Muscat; the stationing of galleys or brigantines to sink any ships that do not obtain licenses; about the reduced tax paid to the king of Persia after the expulsion of the Portuguese; and the reference to the two pearl fisheries at Bahrain and Al-Qatif. Since, Tavernier’s account comes after the unknown author’s account, it only confirms what was written by the unknown author in 1671. In fact, the two accounts being close and independent of one another are mutually complementary, one confirming the others account and vice versa.

Other significant facts that emerges from the account of the unknown author, are that in the 17th-century most of the pearls from the Persian Gulf reached the markets in India as they were offered better prices than the western pearl markets, and after the expulsion of the Portuguese the Persian Gulf fishery was prosecuted mainly by the Persians, who collected a much-reduced tax from the pearl fisherman.

The history of the Persian Gulf from the mid 17th-century to early 20th-century

The history of Iran from 1588 to 1896

Shah Abbas I was the most successful ruler of the Safavid dynasty

Shah Abbas I was the most successful ruler of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, who reigned between 1588 and 1629. He shifted the capital to Isfahan, which he developed into a modern capital city, with palaces and gardens, mosques, schools and bridges, most of which still stand today; and developing trade ties with the west, exporting Iranian carpets, silks and textiles. He successfully fought and recaptured Iranian lands seized by its neighbors, the Ottoman Turks, the Uzbeks, and the Mughals, and expelled the Portuguese from Bahrain in 1602, and later from Bandar Abbas in 1615, the port city situated in the mainland, at the Persian end of the Strait of Hormuz, which Shah Abbas named after himself. In 1622, with the help of the British navy he also expelled the Portuguese from the Island of Hormuz.

Shah Abbas I of Persia

The Safavid dynasty begins its decline after the death of Shah Abbas I, and eventually ends with the invasion of the Afghans in 1722.

The Safavid dynasty began its decline after Shah Abbas I who died in 1629. Shah Abbas was succeeded by his grandson, Shah Safi who was a weak ruler and reigned until his death in 1642. During Shah Safi’s rule most of the territorial gains achieved by Shah Abbas I was reversed. Shah Safi was succeeded by his 10-year old son Sultan Muhammad Mirza, who took the title Shah Abbas II, the Grand Vizier acting as regent to the minor king. It was during Shah Abbas II’s rule, that the Imam of Muscat attacked and occupied the Island of Hormuz in 1650, and subsequently parts of the Persian side of the Gulf. After the death of Shah Abbas II in 1666, the decline of the Safavid dynasty continued attributed to lavish life styles of the Shahs, corruption of government officials, imposition of heavy taxes on people and businesses. During the reign of Shah Sultan Hussein (1694-1722), Mahmud, the ambitious son of Mir Vays Khan who previously captured Kandahar from the Persians in 1709, raised a huge army of 20,000 men and invaded Iran in 1722, besieging the capital Isfahan. After a six-month siege, Shah Sultan Hussein surrendered, and was executed by the Afghan army, ending the Safavid rule of Iran. The Afghan soldiers plundered the wealth of Isfahan, including the crown jewels of the former Shahs of the Safavid dynasty and other dynasties.

Shah Safi of Persia

The vacuum created by the demise of the Safavid dynasty was filled by Nadir Shah, a brilliant soldier who created an empire that rivaled the ancient Iranian empires in extent

Tahmasp II, the son of the executed king Sultan Hussain sought to regain his father’s lost throne, and was assisted by Nadir Qoli Beg, who raised an army of 5,000 soldiers that moved against the Afghans and defeated them at Damghan in October 1729, driving them out of Persia. Thamsp II was restored to the Iranian throne, but was soon deposed by Nadir Shah who installed Tahmasp’s infant son Abbas III on the throne, and acted as regent to the young king. He deposed the young Abbas III in 1736. Nadir Shah moved against the Ottoman Turks driving them out of Iranian territories, Azerbaijan and Iraq. He then annexed the Caspian provinces of Russia; Herat, Kandahar and Kabul in Afghanistan; Bahrain, and Oman in the Persian Gulf; Yerevan in Armenia another Ottoman territory; Bukhara and Khiva in Afghanistan. The extent of the empire created by Nadir Shah was almost equal to the ancient Iranian empires. Nadir Shah also attacked and captured Delhi and Agra from the Mughal emperors, taking an enormous booty in return for leaving the country. Nadir Shah, though a brilliant soldier, failed as a statesman and administrator. The country became tired of his ruthless and harsh rule, and the never ending military campaigns.

Nadir Shah

The Assassination of Nadir Shah in 1747 caused the disintegration of Iran into three separate kingdoms out of which the Qajar kingdom prevails

Eventually Nadir Shah was assassinated in 1747, that not only led to the disintegration of the empire he created but also the country of Iran itself which split into three kingdoms. A kingdom based in Khorasan with Mashhad as capital headed by Shah Rukh, the blind grandson of Nadir Shah; A second kingdom based in Mazanderan headed by Muhammad Hassan Khan Qajar, the Qajar chief; a third kingdom based in central and southern Iran, with the capital at Shiraz, headed by Muhammad Karim Khan Zand of the Zand dynasty. The Qajar kingdom eventually prevailed, defeating the Zand kingdom and the Afsharid kingdom of Shah Rukh, and re-uniting Iran in 1796. The Qajar dynasty was founded by Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar in 1796, who assumed the title of Shahanshah. However, more political instability was to follow, when Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar was assassinated in 1797, while on an expedition to Georgia. Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar was succeeded by his nephew, Fath Ali Shah, whose rule from 1797 to 1834 ushered in an era of stability to Iran, after the long period of instability caused since the death of Shah Abbas I in 1629. Fath Ali Shah was succeeded by his grandson Muhammad Shah (1834-48), who in turn was succeeded by his son Nasser-ed-Din Shah, the most successful of the Qajar rulers, who ruled from 1848 to 1896, and was responsible for the modernization of Iran on the western model.

The History of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery from the 18th-century to the early 20th-century

The political instability of the 18th-century in Iran resulted in Iran loosing its grip on the pearl industry of the Persian Gulf, and the development of alternative pearling centers on the Arab side of the Gulf

After a short period of control of the Persian coastline of the Persian Gulf in the mid 17th-century by the Imam of Muscat and Oman, the Safavid Shahs again regained control of their territory. Since the ousting of the Portuguese from the Persian Gulf, in the mid 17th-century, the pearl fisheries of the Gulf, were mainly prosecuted by the Persians. Thus, any political instability or turmoil in Iran, caused disruptions in pearling activities in the Gulf. However, in spite of disruptions, fluctuations and decline in production, a substantial pearling industry is believed to have existed in the late 17th-century and early 18th-centuries. The greatest disruptions came in 1722, during the Afghan invasion of Iran and the killing of the Safavid Shah Sultan Hussein, and again in 1747, when the Iranian nation disintegrated into three separate kingdoms following the assassination of Nadir Shah, a status quo that lasted until 1796, when the founder of the Qajar dynasty, Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar, reunited the country. The political instability of the 18th-century in Iran, resulted in Iran loosing its grip on the pearl industry of the Persian Gulf. The resultant failure to collect tax revenues, gave rise to new economic opportunities for the Arab communities of the Gulf, who settled and founded new pearling centers. Thus, the Arab communities of the Gulf, capitalized on the weakness of the Persian state, and set up several alternating pearling centers on the Arab side of the Gulf. However, Bahrain continued to maintain its importance as the main pearling center in the Gulf, the pearl banks around the island being the most lucrative in the entire Gulf. Following the death of Nadir Shah in 1747, control over Bahrain and its pearl market swung between the Persians on one side of the Gulf and various tribal rulers on the other side of the Gulf, which led to the Al-Khalifa consolidating power in 1783. As a result, the ruler of Bahrain, the Sheik of Abooshahar (Bushehr) was not able to collect tax from the pearl fisherman, visiting the banks around Bahrain, leading to the erosion of Bahrain’s monopoly on the Pearl trade.

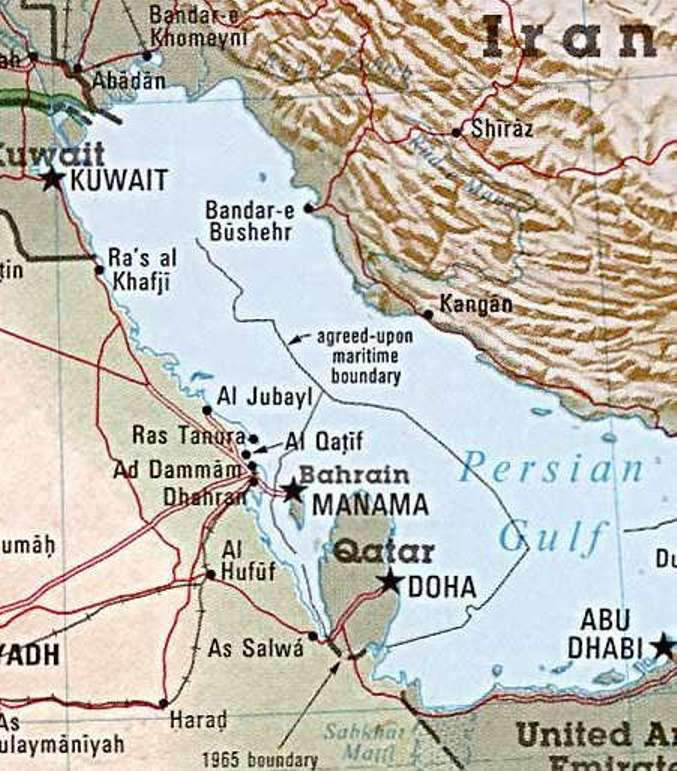

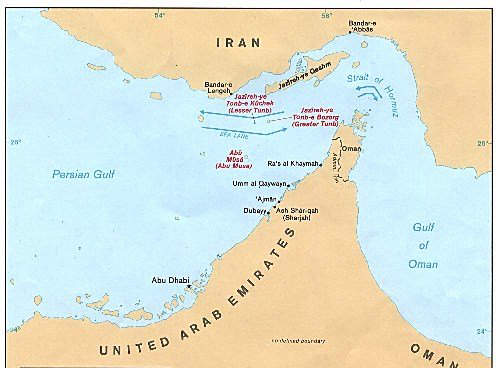

Map of the Persian Gulf, showing the pearling centers of Kuwait, Al-Qatif, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi on the Arabian side of the gulf and Bushehr on the Persian side of the gulf.

The ascendancy of the Al-Khalifa clan that set up new pearling settlements in Kuwait, Abu Dhabi and Qatar in the late 18th-century

The Al-Khalifa first moved to Qatar and then Bahrain, with the intention of procuring a share of the fishery for themselves, instead of continuing to purchase from other hands. They also urged their fellow Utubi families, the Al-Sabah and Jalahama, to accompany them and devote themselves to pearl fishing. This led to the establishment of new settlements for pearl fishing, such as Kuwait, a town founded in 1710, but declared an independent sheikdom in 1756; Abu Dhabi founded in 1761 and Qatar (Zubara) founded in 1766. The new settlements grew rapidly, with Kuwait having a pearling and fishing fleet of 800 vessels in 1763 and Abu Dhabi having 400 houses in the same year, just two years after its founding. The old pearling centers such as Bahrain, Julfar, Al-Qatif, and lesser centers such as Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al-Qaiwan, continued to co-exist with the new settlements. The setting up of new pearling settlements led to a revival of the pearling industry in the Gulf, that also coincided with the beginning of a boom in the pearl industry, caused by an increase in demand for pearls in the western markets and India, that lasted well into the 20th-century, until the advent of the cultured pearl. The pearling industry became so lucrative that settlements were established even in areas with arid climates and sparse water supplies, with no agricultural hinterland, previously considered unsuitable for such settlements. Kuwait and Abu Dhabi were two such new pearling settlements

The problem of piracy on the coastline from Ras al-Khaimah up to Qatar, known as the “Pirate Coast”

The trying circumstances of life in the pirate coast that led some maritime tribes to resort to acts of piracy

Pearling settlements between Ras al-Khaimah and Qatar, such as Sharjah, Dubai, Ajman, Umm Al-Qaiwan and the new settlement of Abu Dhabi, were situated in arid areas, with sparse water supplies, with no agricultural hinterland sufficient to support their increasing pearling populations. The soil was barren and infertile and unable to support the inhabitants. Thus, the pearling centers of this region existed beyond the carrying capacity of their subsistence base. Hence, their populations were heavily dependent on pearling for their day to day survival. These were some of the trying circumstances that led some inhabitants of these regions, whose usual vocation was pearl diving, to resort to the more lucrative acts of piracy, attacking international shipping in the Persian Gulf, belonging to western nations such as the British, Dutch, French, Spain and Portugal, operating in the Persian Gulf, on the east-west trade route, originating mainly from India, and terminating in Gulf ports such as Kuwait, Al-Qatif etc. for the onward land journey to Europe. Such acts of piracy continued unabated for almost 200 years from the mid-17th to mid-19th centuries, the affected coastal area of the Gulf earning the infamous name of “Pirate Coast.” The rise of piracy on the Pirate Coast was associated with the rise of Wahabbism in Arabia, and in fact it was reported that most of the pirates themselves were Wahabbis.

British and Omani intervention in 1819 that eventually led to the signing of a permanent truce in 1835, that created the “Trucial States” and brought an end to all acts of piracy

The rise of piracy reached menacing levels in the early 19th-century, that Britain was forced to send its naval forces stationed in Bombay to intervene in 1819,to protect shipping in the area. Britain together with the forces of the Imam of Muscat and Oman attacked the pirate coast, that eventually led to the signing of a temporary truce between Britain and the Sheikdoms of the Pirate Coast, that decreased the number of pirate attacks, and eventually a permanent treaty in 1835 that put a stop to all acts of piracy, the Sheikdoms acquiring the name “Trucial States.” Under the terms of this treaty the British did not interfere in the governance of these states, but provided security for the states, protecting them from aggression by land or by sea. Any dispute between the states were referred to the British for settlement. After the British Withdrawal of 1971 the “Trucial States” formed a union known as the United Arab Emirates. After the British intervention of 1819 and the signing of the temporary truce in 1820, the maritime tribes of the Pirate Coast were once again encouraged to go back to their traditional vocation, pearl fishing, that had sustained their ancestors for centuries. Thus, their was a revival of the pearl fishing industry on the Pirate Coast after 1835, that provided employment and attractive returns, with the boom in the pearl industry in the late 19th-century

The Persian Gulf pearl fishery in the 18th-century

The Persian Gulf, the only important source of pearls in the world in the 18th-century

During the 18th-century, the Persian Gulf became the only important source of supply for pearls in the world, and was prosecuted vigorously both on the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf, although the Persians lost control of the fishery on the Arabian side of the Gulf, due to political instability in Iran. The vigorous prosecution of the pearl fisheries in the 18-th century was to cater to the increase in demand for pearls not only by the Oriental courts, such as the courts of the Mughal empire, but also the courts of Europe, as well as the wealth and fashion of Europe. The main beneficiaries of pearling on the Arabian side of the Gulf were the Arab Sheikdoms both old, such as Kuwait (1710) and the newly founded ones, such as Abu Dhabi (1761) and Qatar (1766). The reason for the prominence of the pearl fishery of the Gulf, in the 18th-century was the impoverished state of the pearl fisheries of the Gulf of Mannar and those of southern and central America, such as Venezuela and Panama.

The possible causes for a lesser number of pearl fisheries conducted in the Gulf of Mannar under Dutch control in the 18th-century

In the Gulf of Mannar, the pearl fishery was under the control of the Dutch from 1658 to 1796, both on the Indian and Sri Lankan sides of the Gulf. During this period of 138 years of Dutch colonization, only 12 pearl fisheries were held on the Indian side of the Gulf and 11 pearl fisheries on the Sri Lankan side. The possible reasons given for the lesser number of pearl fisheries were overexploitation, unsuitable weather conditions, strong underwater currents, or other unknown factors that led to sparse oyster populations or due to political considerations such as the pressing demands of the Nawab of the Carnatic, with respect to sharing of profits of the fisheries both on the Indian and Sri Lankan sides of the Gulf, that led to the Dutch postponing the fishery indefinitely after 1768. In fact no fisheries were held at all by the Dutch on the Sri Lankan side of the Gulf after 1768, and only three fisheries on the Indian side of the Gulf. The deliberate postponement of the fisheries by the Dutch after 1768, led to very high yields of oysters in the fisheries conducted on the Sri Lankan side of the Gulf, successively in the years 1796, 1797 and 1798, after the British take over of the fisheries in 1796. During this period international attention was diverted towards the Sri Lankan pearl fisheries, away from the Persian Gulf fisheries, but soon the Persian Gulf once again regained its prime position.

Venezuela which was a major international player in the pearl industry in the 16th and 17th centuries, became an insignificant producer in the late 17th-century, a status quo that prevailed even in the 18th-century

In the New World since the discovery of pearls for the first time by Christopher Columbus in 1498, off the island of Cubagua in northeastern Venezuela, the Spanish exploited the lucrative pearl banks of Cubagua extensively and continuously for almost 150 years, until the mid 17th-century, when the pearl banks were severely depleted and totally abandoned. Pearls banks discovered later around the islands off the Pacific coast of Panama and in the Gulf of California, in Mexico, were also exploited by the Spanish, but were not as lucrative as the Venezuelan pearl banks. Statistics of the harvest of pearls taken during this period indicate the extent to which such exploitation had taken place. It was estimated that between 1513 and 1530 at least 118 million pearls were harvested near Cubagua island. In 1527, the total weight of pearls harvested in Venezuela was said to be 1,380 kg. The pearl harvesting industry was the first and greatest single industry of the Europeans in the New World, that gave lucrative economic returns, before the discovery of gold, silver and other minerals. It is the lure of quick economic gains that led the Spanish to exploit the pearl banks year in and year out, to the maximum extent possible, that ultimately led to the total depletion of the oyster resources, around the mid 17th-century, with no immediate prospect of their regeneration and revival. Thus, Venezuela which was the main source of supply for pearls in the world during the 16th and major part of 17th centuries, became an insignificant source in the late 17th-century. The status quo continued into the 18th century. The Persian Gulf which together with the Gulf of Mannar was the hub of the international pearl trade from time immemorial once again regained its status as an international player in the pearl industry, after the Venezuelan pearl banks were totally exhausted.

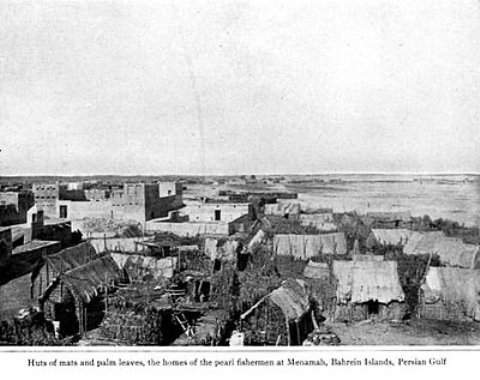

Pearl Fishing Huts in Baharain

A Pearl Fishing Boat

Estimation of the value of the pearl fishery around the island of Bahrain from 1689 A.D. to 1790 A.D. show a definite boom in the prices of pearls after mid 18th-century.

According to records of the British East India Company, in 1675, Captain John Weddell referred to the rich pearl fisheries of the Gulf and mentioned Bahrain as the main center of the pearl fishery. A few years later John Chardin reported that the pearl fishery which was particularly rich around Bahrain, provided one million pearls annually. John Ovington in 1689 A.D. gave an estimate of the income received annually by the Shah of Iran from the pearl banks of Bahrain, which he placed at 50,000 ducats, but believes that the Shah’s servants, which probably included his representative in Bahrain and his tax collectors, siphoned off double that amount. An estimate of the value of the pearl fishery around the island of Bahrain comes in 1754 from Baron von Kniphausen, who placed it at around 240,000 rupees annually under Nadir Shah’s reign from 1736 to 1747, in the early 18th-century. For late 18th-century estimates of the value of the pearl fishery around the island of Bahrain comes in 1770 A.D., 1775 A.D. and 1790 A.D. Justamond and Raynal estimated in 1770 A.D. that the annual revenue from the pearl fishery of Bahrain was 3,600,000 French livres, equivalent to £157,500. Abraham Parsons said in 1775 A.D. that the annual revenue from the Bahrain fishery varied between £112,500 and £187,500. In 1790 A.D. Manesty and Jones reported that Bahrain’s pearl fishery yielded 500,000 rupees annually, despite a drop in productivity. Comparison between the annual revenue of 1736 to 1747 amounting to 240,000 rupees and the revenue of 1790 A.D. amounting to 500,000 rupees, show a definite enhancement in the revenue derived from pearl harvesting, despite decrease in production. This was attributed to a boom in the value of pearls after mid 18th-century, that continued through out the 19th-century.

The Persian Gulf pearl fishery in the 19th-century

Robert Taylor and Wilson on the pearl fishery around Bahrain island in 1818 and 1829

There are ample well authenticated sources that refer to the status of the pearl fishery in the Persian Gulf in the 19th-century, such as official reports originating from the British Resident based in the Persian Gulf, or officers of the British Protectorate of the Persian Gulf. Captain Robert Taylor reported in 1818 A.D. that Bahrain employed 1,400 boats and 32,000 men in their annual pearl fishery, whose turnover amounted to 100,000 Basra Tomans. He also gave various statistics on the fisheries of the ports on the Persian side of the Gulf, as well as those on the Arabian side of the Gulf, and is reported to have stated that the Persian Gulf still possessed “beds of the richest pearls in the universe.” Again in 1820 A.D. George Brucks reported that the sheikdom of Sharjah sent out 300 to 400 pearling boats to take part in the annual pearl fishery. Wilson reported in 1829 A.D. that in Bahrain around 1,500 pearling boats participated in the annual pearl fishery, and estimated that the turnover from the fishery amounted to between £200,000 and £240,000.This value compared with the annual turnover of £112,500 to £187,500 for the Bahrain pearl fishery, as reported by Abraham Parsons in 1775 A.D. shows that the boom in the value of pearls, that began in the mid-18th century, continued into the 19th-century as well, the turnover showing a steady increase in the value of pearls, mainly due to an increase in demand for pearls and not due to an increase in production.

Lieutenant J.R. Wellsted on the status of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery around 1835, as published in his book, “Travels in Arabia” published in London in 1838

Lieutenant J.R. Wellsted, an officer in the Indian Navy, who undertook an exploration of the Persian Gulf in the early 19th-century, gave an interesting description of pearl-fishing as then conducted in the Gulf, in an account of his travels published in 1838. In his account he gave the extent and distribution of the pearl banks; the composition and depth at which they were situated; the season for pearl-fishing in the Gulf; the range in size and number of boats taking part in the fishery; the number of men manning each boat; the total number of men employed in the fishery and the estimated value of the fishery. According to him the pearl banks extended from Sharjah to the islands of the Biddulph’s group. The substrate of the pearl banks were composed of shells, sand and broken corals, and the finest pearls by experience have been found to occur in oysters living in association with corals, as in northwest coast of Australia. The pearl fishing season in the Persian Gulf extended from June to September. The size of the boats employed in the fishery varied from 10 to 50 tons, carrying a crew varying from 8 to 40 men. Out of 4,300 boats employed in the fishery, 3500 came from the Island of Bahrain; 100 from the Persian coast; and 700 from the region between Bahrain and the entrance to the Gulf, including the former pirate coast. The total number of men employed in all the boats, such as divers, assistants etc. were estimated to be around 30,000.The total value of the pearls harvested annually from the Persian Gulf around this time was estimated approximately to be £400,000. The men working on the boats were not paid any wages, but had a share of the profits. A small tax was also levied on each boat taking part in the fishery, by the Sheik of the port to which the boat belonged. During the period of the fishery the pearl fisherman lived on dates and fish.

A first-hand account of the method of pearl fishing in the Persian Gulf in 1835 as observed by J.R. Wellsted

The following is an extract from the book “Travels in Arabia” – a record of the travels of Lieutenant J. R. Wellsted published in 1838 – pertaining to the method of pearl fishing in the Persian Gulf as personally observed by him, during his travels in the Persian Gulf, and also the dangers faced by the pearl divers.

“When about to proceed to business, they divide themselves into two parties, one of which remains in the boat to haul up the others, who are engaged in diving. The latter, having provided themselves with a small basket, jump overboard, and place their feet on a stone, to which a line is attached. Upon a given signal this is let go, and they sink with it to the bottom. When the oysters are thickly clustered, eight or ten may be procured at each descent ; the line is then jerked, and the person stationed in the boat hauls the diver up with as much rapidity as possible. The period during which they can remain under water has been much over-rated ; one minute is the average, and I never knew them but on one occasion, to exceed a minute and a half.”

Among the dangers of the pearler in the Persian Gulf, the dreaded saw-fish may be mentioned as the chief enemy. This shark-like creature is furnished with a formidable weapon in the shape of a flat projecting snout, reaching a length of perhaps six feet, and armed along its edges with strong tooth-like spines. In the presence of such a terrific weapon the diver is almost powerless, and instances are recorded in which the poor fellows have been completely cut in two. Nor are the attacks of saw-fishes and sharks the only sources of danger. ” Diving is considered very detrimental to health, and without doubt it shortens the life of those who much practice it. In order to aid the retention of breath, the diver places a piece of elastic horn over his nostrils, which binds them closely together. He does not enter the boat each time he rises to the surface, ropes being attached to the sides, to which he clings, until he has obtained breath for another attempt.”

The method of pearl fishing described by Wellsted is essentially the same as that described by Lodovico Barthema, the Portuguese explorer in 1508 or by Marcopolo, the Venetian traveler and writer as observed in the Gulf of Mannar, several centuries earlier, in 1290 A.D., except for minor but significant differences, such as the use of elastic horns to close the nostrils, in order to aid the retention of breath, a procedure not adopted by divers in the Gulf of Mannar.

Whitelock on the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in 1836

Whitelock reported in 1836, that the Al-Qawasim territories (former Pirate Coast) sent out around 350 pearling boats annually to take part in the pearl fishery. He further reported that a total of around 3,000 boats and 29,000 men were involved as a whole in the annual Persian Gulf pearl fishery.

The Persian Gulf pearl fishery in 1865 according to Sir Lewis Pelly, the British political resident in the Persian Gulf

Colonel Sir Lewis Pelly, the British political resident in the Persian Gulf, prepared an official report on the Bahrain pearl fishery in 1865. According to this report the richest pearl banks in the Persian Gulf were those around the island of Bahrain, where oysters were found at all depths, from a little below high-water mark down to 18 fathoms. The Arabs who monopolized the right of fishing on all the banks along the Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf, clung to the old belief that the luster of the pearl depended on the depth of water in which the oyster lived. The most productive banks were formed of fine light-colored sand, overlying coral-rocks. The report further stated that Bahrain alone employed about 1,500 boats in this industry, and the fishing that took place annually yielded a profit of about £400,000 a year, which agreed with what Wellsted reported in 1838.

The value of the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in 1878/1879 as reported by the British Resident Colonel Ross and Captain Durand of the British protectorate

In 1879 Colonel Ross, the British Resident in the Persian Gulf estimated that the value of the Persian Gulf fishery was around £600,000. Captain L. E. Durand of the British Protectorate of the Persian Gulf estimated one year earlier in 1878 that the value of the fishery was around £800,000. According to Captain Durand there had been a decrease in the yield of oysters in the Persian Gulf in the 19th-century due to the increase in demand for pearls and the resultant over-fishing. However, according to him the problem of decreased yields was offset by a doubling of prices since 1850s. In other words since 1850s the supply of pearls could not match the demand, resulting in an increase in prices. The value of the pearl fishery increasing from around £400,000 in 1865 to around £800,000 in 1878, seem to agree with Captain Durand’s observation.

Samuel M. Zwemer on the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in 1896 in his book the “Cradle of Islam”

Zwemer Samuel M. in his book the “Cradle of Islam” published in 1900 refers to the Persian Gulf pearl fishery that took place in 1896 A.D. According to him around 5,000 pearling boats took part in the pearl fishery of the Persian Gulf, out of which nearly a 1,000 boats came from Bahrain and 200 boats from Qatar. Around 30,000 men were employed in the pearl fishery and the value of the pearls shipped from Bahrain in 1896 was £303,941 when the value of the entire pearl fishery was £1,602,800. Thus, the value of the pearl fishery which was around £800,000 in 1878 according to Captain Durand, increased by two fold to around £1.6 million in 1896.

The Persian Gulf pearl fishery in the 20th-century

Information on the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in the early 20th-century comes from Lorimer

Our information on the Persian Gulf pearl fishery in the early 20th-century, from 1900 to 1915, comes from Lorimer’s “Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia” that contains an enormous volume of qualitative and quantitative data relevant to the pearl trade in the Persian Gulf.

A comparison of the value of pearls exported by the Trucial States, Bahrain and the Persian coast from 1873 to 1904

Among some of the interesting statistics provided by Lorimer was the “Statistics of the Value of Pearls Exported Annually from the Principal Emporia of the Persian Gulf between 1873 and 1904” given in rupees The principal emporia included the Trucial States, Bahrain and the Persian Coast. The total value of pearls exported from the Persian Gulf was obtained by adding together the annual exports of the three emporia. An approximate value of these pearl exports in British pounds can be obtained using the exchange rate of one pound to 10 rupees

Statistics of the Value of Pearls Exported Annually from the Principal Emporia of the Persian Gulf between 1873 and 1904, extracted from Lorimer’s Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia

| Year | Trucial States | Bahrain | Persian Coast | Total |

| 1873 | 1180000 | 2100000 | 4596500 | 7876500 |

| 1874 | 1200000 | 2100000 | 5700000 | 9000000 |

| 1875 | 1490000 | 2800000 | 3200000 | 7490000 |

| 1876 | 1000000 | 2175000 | 2372000 | 5547000 |

| 1877 | 2124200 | 1850000 | 2395000 | 6369200 |

| 1878 | 1216560 | 1520000 | 2995000 | 5731560 |

| 1879 | 1400000 | 1811000 | 2240000 | 5451000 |

| 1880 | 3050000 | 2023000 | 2276000 | 7349000 |

| 1881 | 2665000 | 1586000 | 2847000 | 7098000 |

| 1882 | 2287000 | 1659000 | 2398000 | 6344000 |

| 1883 | 2822000 | 1877500 | 2680100 | 7379600 |

| 1884 | 3978000 | 2312000 | 2684900 | 8974900 |

| 1885 | 2600000 | 1744000 | 3120000 | 7464000 |

| 1886 | 1800000 | 1821000 | 2572700 | 6193700 |

| 1887 | 2600000 | 2493500 | 3207500 | 8301000 |

| 1888 | 5000000 | 3207000 | 4353000 | 12560000 |

| 1889 | 4000000 | 3331000 | 4498000 | 11829000 |

| 1890 | 2700000 | 3876000 | 3226700 | 9802700 |

| 1891 | 3500000 | 4231000 | 4129500 | 11860500 |

| 1892 | 5250000 | 4925000 | 4855000 | 15030000 |

| 1893 | 5000000 | 3693750 | 4213440 | 12907190 |

| 1894 | 6000000 | 4658620 | 3935200 | 14593820 |

| 1895 | 8000000 | 3855000 | 4173000 | 16028000 |

| 1896 | 10000000 | 5167000 | 3865000 | 19032000 |

| 1897 | 7500000 | 3911000 | 3587600 | 14998600 |

| 1898 | 5500000 | 4793000 | 3871000 | 14164000 |

| 1899 | 7749990 | 6824430 | 3451905 | 18026325 |

| 1900 | 4200000 | 3961700 | 2750000 | 10911700 |

| 1901 | 5000000 | 7130100 | 4028500 | 16158600 |

| 1902 | 8000000 | 8495610 | 7043673 | 23539283 |

| 1903 | 9000000 | 10275300 | 4905000 | 24180300 |

| 1904 | 5000000 | 10488000 | 626600 | 16114600 |

Information that can be derived from the above table

1) In the green bold rows from 1873 to 1879 the value of the exports for the Persian coast was the highest, and the Trucial States the lowest, with Bahrain exports having an intermediate value. This trend is also seen in the years 1881-82, 1885-87, 1889. However, in the years 1877, 1881, 1882, 1885, 1887 and 1889, the Trucial States had the intermediate value and Bahrain the lowest.